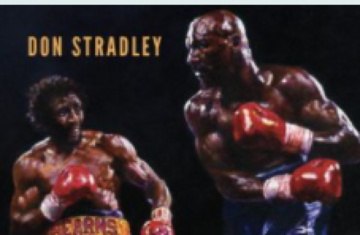

THE FOLLOWING passage is an extract from The War: Hagler-Hearns and Three Rounds for the Ages, by Don Stradley (Hamilcar Publications, September 2021).

It was estimated that 25,000 people were on Caesars Palace property on the day of the fight.

They stood shoulder to shoulder in crowded areas, jam-packed the restrooms, the casino, admission lines, valet parking areas, and food-and-drink lines. Hundreds who didn’t have tickets for the fight lingered around, just wanting to be part of this national moment.

Journalist Pete Hamill was aghast at the wave of humanity flooding into “this tacky desert town . . . . All day they came piling out of cabs and airport limousines: cartoon Detroit pimps, overdone fancy ladies, bi-continental drug dealers, weighed down by chains, medallions and Rolexes.

“They were here for Hearns and Hagler, of course, but Sinatra also was at the Golden Nugget for two nights, so you could see second-rate hoodlums from the East, all blue hair and plastic teeth, flipping silver dollars in the lobbies . . . all wandering through the neon wilderness of girlie shows, 99-cent breakfasts, second-rate entertainers and the pervasive, intoxicating apparatus of gambling.”

There were also 40,000 or so people in town for the National Association of Broadcasters convention. This additional crowd, along with temperatures that neared 100 degrees, gave the Strip an overstuffed and overheated atmosphere. In the soaring heat, three of Hearns’s brothers, Billy, John, and Jesse, worked a concession stand across the street from Caesars Palace, earning $2,500 a day selling Hit Man souvenirs.

Meanwhile, Hector Camacho occupied a spot by the Caesars Palace swimming pool in nothing but some gold jewellery, blue sneakers, and a leopard-skin, slingshot bikini. Trying to snatch a bit of spotlight for himself, the 22-year-old Puerto Rican lightweight burst into a loud rendition of Madonna’s hit from the previous fall, “Like a Virgin.”

While Camacho sang and strutted, artist LeRoy Neiman sketched him. When Neiman presented the finished drawing, Camacho asked him to pencil in more muscles.

The swimming pool was a spectacle in itself, and one had to pass it in order to get to the lot where the boxing ring was set up. “The bodies there,” wrote Mike Downey, “stretched out on lawn chairs, remind you of the scene in Gone with the Wind where dying soldiers are lined up along the railroad tracks.” The difference, Downey added, was that the pool crowd could make you gag “on the overwhelming smell of Hawaiian Tropic and Coppertone.”

The day before the fight, Jake LaMotta was poolside, crooning a song to his new bride, Theresa Miller. LaMotta had been part of the Hagler–Hearns promotion since the beginning, getting paid by Arum to linger at press conferences and talk about the fight. His tour of duty climaxed on the night before the contest with a wedding ceremony, his sixth, at Maxim’s ballroom. LaMotta, whose sordid life was depicted in the 1980 film Raging Bull, had become a kind of fringe celebrity, known mostly for bad jokes. “My first wife divorced me because I clashed with the drapes,” he liked to say.

Donald Curry and Milton McCory, two young welterweights who would soon be in their own million-dollar event, were asked to help video technicians with a dress rehearsal the night before the big fight. Curry, a Top Rank fighter, and McCory, who trained at the Kronk, climbed into the ring and jokingly went through the motions of boxing as the crew checked lighting levels. Asked if he and McCory would someday headline a big Las Vegas event like Hagler and Hearns, Curry seemed hopeful. “It’s all about money,” he said.

In a previous era, Hearns and Hagler would’ve fought in New York for much less money and with a lot less hype. But after a slow start in the 1960s, Las Vegas had emerged as boxing’s new stage.

The top fighters were demanding larger purses, and it took the high rollers of Vegas to bankroll them. New York, with its high tax laws, had struggled to attract big fights during the past decade. Atlantic City picked up some of the slack, but Las Vegas was entering a decades-long domination of the big-time boxing scene. As one writer stated on the eve of Hagler–Hearns, “The city specializes in two of boxing’s most important elements, glitz and sleaze.”

Still, many were dubious that boxing would regain its health in Las Vegas. In 1985, Las Vegas was in a depressed midpoint between the Mob years of the 1950s and the swanky corporate theme park it would become in the 2000s. The city was still wobbly from the recent recession, and hotel entertainment was going through a drab period. “Vegas was in full plummet then,” wrote author Adrienne Sharp, “old hotels barely hanging on, not yet imploded and replaced.”

In other words, Hearns was not going to break from training to go enjoy Celine Dion or Cirque du Soleil. Those acts were nowhere near Las Vegas in 1985. One could still see showgirls sporting 12-pound headdresses at Bally’s, or you might catch Dean Martin, still vaguely recognisable from his Rat Pack days.

Liberace, the flamboyant piano man, was 65 and dying of AIDS but still performing at the Hilton. Two German magicians, Siegfried Fischbacher and Uwe Ludwig Horn, were doing well with their tiger act at the Frontier Hotel, but you were just as likely to see female mud wrestling. (Indeed, Hearns was asked if he and Hagler would ever take in some Las Vegas entertainment together. He responded, “The only place I would take Hagler is to a mud-wrestling match so I could throw some mud on him.”)

Of course, provincial sportswriters could always amuse the readers back home with tales of circular beds and mirrored ceilings. For some old-school-type reporters, those accustomed to wholesome ballparks and college basketball, Las Vegas was nothing but a gaudy mecca for the desperate and depraved, proof that civilised life was collapsing. Even the temporary stadium, erected on a pair of tennis courts not far from where Camacho modelled his bikini, was derided.

“It’s a rickety-looking structure,” wrote the Los Angeles Times’ Earl Gustkey, “It doesn’t look much different from the bleachers you might see at the county fairgrounds drag races.”

Some thought the casino mentality would be the sport’s death. After all, Las Vegas was where tired old entertainers went in hopes of extending their careers. To cynics, boxing was another tired act trying to hang on for an encore, while many sportswriters fretted about the constant presence of drug dealers and Mob types, what one Boston correspondent called “the shadow economy coming out into the sunshine.”

When Arum was asked about the questionable clientele that made Las Vegas purr, he was unconcerned. “We’re talking about a place that pays homage, bows down to great amounts of cash money,” Arum said. “Those are the types of people who have it, aren’t they?”

One could have debated whether Las Vegas was attracting creeps to boxing, or if boxing was attracting creeps to Las Vegas, but the Las Vegas Convention and Visitors authority calculated some impressive numbers during the weekend of Hagler–Hearns.

The estimate was that visitors for the fight had spent $92 million, nearly double the amount dropped at Hagler–Duran and Holmes–Cooney, and what one tourism official compared to “four New Year’s Eves.”

While the 40,000 broadcasters in the city no doubt helped with general revenue, the fight was irresistible for gamblers. Herb “Hoops” Lambeck, who made the boxing line used by all Nevada sportsbooks, recalled the mountains of money being risked.

“For Hagler–Hearns there was no federal law on reporting wagers over 10 Gs, like there is now,” he said in 1992. “The action was so tight, both guys were 6-5. I never seen two-way action like that.”

Hagler–Hearns was one of the most legally-bet fights in history to that time, and was such a success that Caesars Palace began toying with the idea of hosting the Super Bowl. Even if the fight didn’t make a dime for Arum or the closed-circuit theatres, it had already made Las Vegas rich.

“Las Vegas was on fire that week,” recalled Al Bernstein. “The event took on a life of its own. During that period, there was nothing like a championship fight atmosphere. Las Vegas was certainly in transition. It was between the Rat Pack era and the corporate era that we have now, but it was closer to the Rat Pack era. It was freewheeling; you could feel the energy flying through the air. Keep in mind, I was a newspaper editor from Chicago, and Las Vegas was not a respected place. People thought of Las Vegas as an absurd cliché, some cornball place your uncle went to. But it was in transition, and boxing was part of the change. I really believe Hagler–Hearns put Las Vegas over the top.”

On the morning of the fight, scalpers were selling Hagler–Hearns tickets for as much as $1,800 dollars, without bargaining. By evening, they’d come down in price, selling some tickets at face value. Along with ticket scalpers, Las Vegas was awash in pimps, prostitutes, petty crooks, and pickpockets, many from out of state, swarming into Caesars Palace like flies.

In response, there were nearly 300 uniformed policemen and security guards on duty, plus an unknown number of undercover detectives. By the end of the day, vice officers had arrested 46 people on 74 charges ranging from larceny, soliciting, disorderly conduct, and battery on a police officer. The Las Vegas police reported that it was a record number of arrests for a boxing event, with “thieves coming from all over the country.”

One of the more colourful incidents involved former heavyweight champion Leon Spinks. At 5:15 am, police were called to Botany’s Restaurant on East Flamingo Road where Spinks and a female companion were brawling.

They didn’t arrest “Neon Leon,” but escorted him out of the tavern to his car and sent him away. The restaurant manager claimed Leon had started the fracas by slapping the woman, but she threw punches right back and the two were soon on the floor, grappling. The manager said of Leon’s date, “She had a great left hook.”

The War: Hagler-Hearns and Three Rounds for the Ages, by Don Stradley is published by Hamilcar Publications. More info here.

Enjoy Playing in the Scottish Third Division. ahahahahaha.

Celtic SPL Champions 2012-2013. Up The Hoops

As a Celtic fan I can see the horrible effect this will have on Celtic and the whole league in scotland it’s going to take 8 years before rangers are back in the spl I honestly can see them being stuck in division 2 for 2 years and div 1 for a couple more, as for Celtic it will make the spl as bad as the loi and will spell the end of Celtic being any kinda challenge in the early stages in Europe cause lets face it there not great as it is now , anyway after that all I can say is

Come in the hoops