THE NEXT RACE.

That’s what it always came back to. The next run, the next session, the next fight. Nobody died. Tomorrow is another day.

Fourth at the 1992 Olympics? Next race.

First-ever woman to win the 5,000m final at the 1995 World Championships? Next race.

Coming last in Atlanta, out of sorts and unable to finish? Next race.

A silver medal at the Sydney Olympics? Next. Race.

Easy to remember but not always easy to follow. In an athletics career that swung unpredictably from incredible highs to incredible lows, thinking about the next race was sometimes unfathomable.

But even in the times when it was difficult to find the resolve, this maxim found a way through into her psyche. She had it all along.

From her formative days as a runner in Cobh, this was the trait that distinguished her from everyone else in the eyes of her first coach, Seán Kennedy.

The local Cobh man gave her running programmes that were designed to break her but she never gave in. Many other athletes attempted his regime, but didn’t have the stomach for it.

Sonia would take all the nexts that were coming.

It took Kennedy just three weeks to realise he had a special talent on his books.

“I thought, ‘this is something else,’ he tells The42 on a sunny November day in Cobh.

The stuff I was giving her, you don’t come back after three weeks and look for more. Hail, ran or snow. She was looking for more and more and more.”

The beginning of the beginning

It was never Sonia O’Sullivan. Irish people knew her only as Sonia.

Sonia O’Sullivan was something that appeared in race lists on television screens before she was about to run. But as those events beamed into sitting rooms across the country, we were all on first-name terms with the woman in the Irish singlet.

In Cobh, she was Sonia too. She wasn’t just the daughter of John and Mary. Her first name was familiar to people around the town from a young age.

She was the girl who was haring around the roads, the fields and the hills in accordance with Kennedy’s prescribed running programme. During her years attending Cobh Community College, she would duck out after school to fit in a run before doing her homework.

Not that her studies ever suffered at the expense of her running. Her old Irish teacher Ms Mary Smiddy smiles as she tells The42 that her will to achieve came through in the academic sphere too.

She even used her Irish oral exam to make a prediction about her future in athletics.

From the beginning, you could see the determination. In her Leaving Cert oral, she told us she was going to be in the Olympics. We said ‘yeah’ but didn’t realise she would.

Smiddy continues: ”Way back then, Peig Sayers was the book for the Irish, and 50 paragraphs to read. I suggested anybody could put them on tape if they wanted me to listen to them.

“She was the only one that ever did, and all 50 paragraphs, which would have taken quite a while. Just to make sure she would have got as good [a grade] as she could. She was focused no matter what.”

Tough as those running programmes were, Sonia’s hunger for hard work often got the better of her and she would exceed the amount Kennedy gave to her.

But he always knew when she tried to sneak in extra training. And he knew how best to deal with that.

“Cobh is a very small town,” he says hinting at the local informers who told him of Sonia’s unauthorised movements.

“The population back then was around 8,000 or 9,000. Everyone knew her.

“There were occasions when Sonia would go away and do stuff that she shouldn’t be doing and I’d have subtly readjusted the programme. Not give out to her, because you give out to Sonia at your peril.

“I just subtly adjusted the programme to take in the fact that she’s done something that she shouldn’t be doing.”

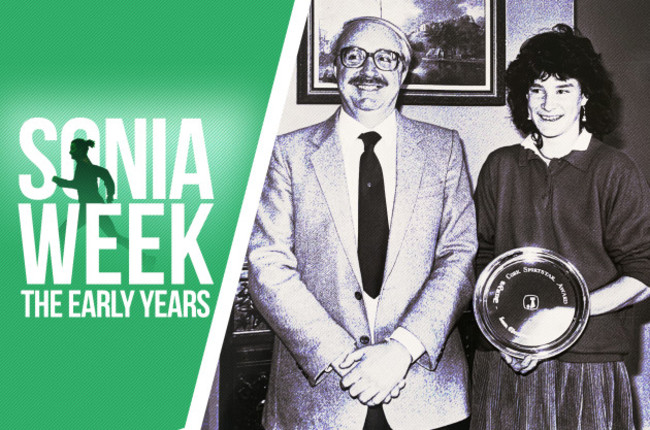

Kennedy began coaching Sonia when she was 13 and it was her first trainer at the Ballymore Cobh Athletic Club, Pat O’Halloran, who brought them together.

“Is there any chance you could look after this lady here, I can’t handle her,” Kennedy says of O’Halloran’s request to take the bundle of energy off his hands.

O’Halloran came from a sprinting background while Kennedy specialised in the longer distances, being a former runner himself.

“He saw the sense in moving Sonia on to somebody who knew what they were doing,” Kennedy adds. “He didn’t impose his training regime on her.

That takes guts to come along and realise that and push on.”

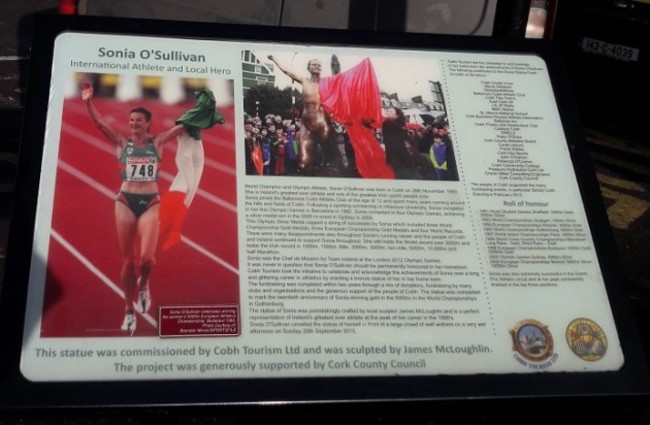

Nothing surprised Kennedy when it came to Sonia. On the day this writer takes a trip to the coastal town in Cork, we visit the bronze statue of Sonia that sits in the heart of the square.

He points to the rippling muscles in the arms of bronze Sonia and reminisces about the weights training she did to achieve that form.

If you saw that little thing lifting weights, my God. We used to go up to Cobh GAA and they had a nice little gym up there. We used to do weights inside there and she was absolutely… But even the profile of her arm. That doesn’t just happen, that’s developed.”

Sonia was even talking about ambitions of “going all the way” to become a world champion when she was only 14.

Her first race under Kennedy where she really showcased her potential was on Little Island in Cork. She edged out senior international athlete Valerie Vaughan in a road race that day.

By the time she was 17, Sonia was a national junior and senior cross country champion. She won both titles within the space of a few weeks, although Kennedy didn’t want her to run in the senior race.

“She entered herself and I said to my wife Mary, ‘we better go to Killenaule. If we don’t go there’ll be no-one from Cobh up there.’

“She [Sonia] went on her own with Leevale Athletic Club. I knew she was going to win. She was after winning the All-Ireland junior and All-Ireland Colleges [titles] the same year.

“So I went to Killenaule, pushing a pram up the hill. ‘What are you doing here?’ I said, ‘if you win the race, I want to be here.’

To win the senior race like that and to win it so emphatically, it was colossal stuff. That was it, the beginning of the beginning.”

Stairways to heaven

All the top athletes had something. A weapon that the competition couldn’t handle. In his pomp, Tiger Woods had the death stare. Johan had the Cruyff turn. And Sonia had the kick.

It was a familiar sight that unfolded on the home straight in the last lap of her races. A burst of speed that propelled her away from the field, torching the ground behind her to leave her opponents to perish.

It careered her to victory in the 5,000m final at the 1995 World Championships and left her just a few feet short of an Olympic gold at Sydney in 2000.

“You’ve gotta come off the shoulder,” says Kennedy about how they executed Sonia’s kick.

Working on speed drills was key for developing her kick, but the hills in Cobh played a huge role as well. Kennedy takes us walking up two of the local hills where his protégé built up the strength and speed she needed to kick for home.

Birds Hill is up first. A road between two big fields, it winds and slaloms upwards for 1,000m. All the way to heaven.

It’s a daunting sight looking up from the foot of the hill. And it’s no surprise that we see a cyclist struggling up the incline.

Sonia however, could run it in 4:20. Flat out. Lather, rinse, repeat.

“You see the gradient? What do you think of that?,” Kennedy smiles as we begin the ascent, our breaths getting more and more laboured on the climb.

“She would go up to the top and race back down to the bottom. Turn around below and repeat it four or five times. It would depend on whether she was racing the following Sunday.

Sometimes I wouldn’t be around at all. I’d know whether she was after doing a good session on the hill or not by the following day inside in the field. That’s where she did the easy session.”

In the centre of the town lies the Burma Steps, or the Joseph Mary Plunkett Way. This climb involves a sequence of steps and flat paths that stretch upwards for 800m.

Her very own set of Rocky steps.

“That’s cadence,” Kennedy explains, “That’s different to running a hill. She went up every single step.”

These were the instruments that Sonia used to achieve greatness. And they were right on her doorstep.

No Man’s Land

Sometimes the kick wasn’t enough.

Sometimes she won, other days she medalled. But in the 1992 Olympics, Sonia finished fourth in the 3,000m final. It was her first time to race at the Games, and her last Olympics with Kennedy as her coach.

Sonia was instructed to tuck in behind Scottish runner Yvonne Murray, the bronze medal winner from the 1988 Olympics. When the time came, Sonia’s kick would come into play, Murray would burn, and Sonia would stride for victory. But something happened that neither Kennedy nor Sonia anticipated.

“Yvonne was in front,” Kennedy recalls as he relives that painful sight in Barcelona.

“She died a death and Sonia died a death. There was no Plan B. Bad coaching. I fell off the stool, put my hands over my head and the English crowd were saying ‘are ya alright?’

“I slipped on the ground and I knew it.

I’d say I ran out of the stadium. I didn’t even meet her I’d say. I went down to the pub and got pissed that night. I was staying with John O’Sullivan and her mother [Mary] in a house down in the middle of the town. I went back to the bar and stayed for the rest of the Games.”

There are no medals or spots on the podium for fourth place. It’s no man’s land. Yet she was still just 22 at the time, and on the cusp of an Olympic medal.

“She’s always saying if she’d won that race that’d be it,” Kennedy says pragmatically. “What was she going to do after that?”

Next race.

Better than one defeat

The late sporting broadcast legend Bill O’Herlihy once remarked that Eamonn Coghlan and John Treacy could tell him if an athlete was going to win just by looking at their face on the starting line.

In the moments before the start of the women’s 5,000m final at the 1996 Olympics in Atlanta, they had concerns about Sonia.

By this stage, Kennedy was no longer Sonia’s coach. He happily slotted into the supporter’s role though, and was putting up flags and bunting around Cobh in her honour.

He settled in to watch that 5,000m final at home. The unfortunate thing was that he shared the same gift as Coughlan and Treacy.

“Her whole demeanour was all wrong,” he says thinking back to what he saw in Sonia’s expression before the final.

“There was no zip in her preparation. The look on her face was completely desolate. She’s normally bright and alert. It just wasn’t there that day. She just wasn’t at the races. You get those days. Everyone has them.

“She was totally dehydrated and she had a team around her who should not have let that happen. Now there could have been something else wrong.

You can have all sorts of suppositions about what happened to Sonia that day in Atlanta and no-one will ever know. There could be any number of underlying factors. That’s just it, you get on with the next race.”

Watching Sonia jog off the track with just two laps to go is an image that endures with every Irish person who willed her to do well. In that moment, the people of Cobh were hurting with her.

“I remember the time she didn’t get on well and the devastation and the heartbreak,” says her old teacher Smiddy who still looked out for her former student after she left school to pursue a scholarship at Villanova University in America.

Everyone was writing her off and yet forgetting everything she had done up to that time. I remember writing to her afterwards and saying she was more than that one defeat.”

‘You’re lucky to get that silver’

Sonia finally managed to vanquish the demons of Olympics past in 2000.

And just like before, the Irish fans were behind her and ready to get swept up for another spin.

Today, there’s a wall in Cobh Community College that carries the title “Sonia – three decades of sporting success.” Photographs, an Irish singlet, and a letter from the woman herself are all exhibits of the Sonia museum.

But on Monday, 25 September 19 years ago, Sonia was still without an Olympic medal as she approached the starting line in Sydney. A live screening of the race was held in the school where television cameras captured the locals cheering her on.

“The television was set up and everybody was watching,” Smiddy recounts of that day.

“They [TV cameras] went down to her home place and interviewed people there. TG4 or someone got me on afterwards because I had the Irish.”

Sonia and Kennedy’s patented kick was certainly on show that day. But her Romanian rival Gabriela Szabo, who was leading in the final lap, kicked right alongside the Irishwoman.

“Everyone was up to high doe in here,” says Smiddy of the drama in Cobh during that last lap. “Wound to the last.”

As the pair came round the final bend, it looked as though Sonia had pushed into first place. Atlanta was about to become a mere footnote as her moment of glory beckoned.

But the camera angle deceived us. Szabo maintained her lead, held off Sonia’s charge and snatched the gold medal.

“She was bloody lucky to get a medal out of Sydney,” says the coach in Kennedy. Sonia had drifted out of contention in that final, but managed to claw her way up to the leading pack.

“There were two groups and the first group ran away. For some reason, they slowed down and Sonia came down and got into silver position.

I remember calling her and saying, ‘you’re bloody lucky.’ And she says, ‘I know.’”

Life moves on

People of a certain vintage will remember Ronnie Delaney’s greatest days in athletics. Those who have memories of John Treacy’s achievements are out there too, as are the folk who belong to the Eamonn Coughlan generation.

They remember it all vividly. They have a connection with that athlete. But the years pass by.

There were plenty of historic days in Cobh to celebrate Sonia’s triumphs. The unveiling of her bronze statue brought a gathering in 2015, and there’s even a pilot boat named after their hometown hero, according to Kennedy.

The homecoming parties after her international successes were really the big occasions in the town.

“There wasn’t standing room in the whole square,” Kennedy says thinking back fondly. “We had a band playing and the place was jammed.

The joy and happiness she brought to Cobh during those years when she was winning the Grands Prix and European Championships and the whole town ablaze with posters of Sonia.

“An open-top bus coming in the Fota Road – feckin’ great times. I’ll never forget them. Interviews left, right and centre.

“When you see her running on the roads, you think ‘oh there’s Sonia.’ And then when she was on television you’d think ‘oh she’s living alongside of me.’ And then they were all living alongside Sonia and they could be two miles away.”

Today is business as usual in Cobh. People are moving about the town with messages to run for. Cars are navigating up and down the narrow and windy roads that all seem to melt into each other on the hills. Ships and boats are drifting through Cork Harbour while the roaring sunshine gobbles up the water.

But the years pass by and legacies become diluted. Sonia turns 50 this week. She was approaching her 31st birthday when she won the silver medal in Sydney.

Sonia has often returned to her old school to give talks to the students, but today’s generation can’t identify with her glory years like those who were born a decade before them.

“That’s life,” says Smiddy.

The beginning of the end

In truth, Kennedy knew the end was coming in 1990. Sonia competed in her first senior international race that year, finishing 11th in the 3,000m final at the European Championships in Split, Croatia.

Kennedy continued to work as her coach until after the ’92 Olympics but it was a gradual fade-out up to the end of their coaching relationship. Just as Pat O’Halloran did in those early days of Sonia’s career, Kennedy knew it was time to release her into the services of another coach.

It just fazed out. I did my piece. I was ready, I’d had enough. We had a young family and I needed to concentrate on my work as well.

“At that stage in international [racing], there were agents taking over so I’d been fazed out by then. That’s the way it should be.

“When you go to a manager or agent, they take over everything. They take over the training, the expenses, the sponsorship, the whole lot. I knew that was gonna happen.”

The pair are still in contact. The bond is still strong after all these years.

Speaking at a GAA conference about coaching a few years ago, Sonia even revealed that Kennedy’s phone number is one of the few contacts she still knows by heart.

And when she heard that Kennedy’s son John was left paralysed after suffering a spinal injury in an accident, she contacted to ask how she could help.

Sonia donated her first pair of spikes and a picture to an auction that was held to raise funds for him, where a local man put in the winning bid.

Richard Marshall in the pub came up and asked me to come out to the car,” says Kennedy, picking up the story. “There he was with the pair of spikes and the photograph. He gave them to me and says ‘they’re yours.’

“I was blown away. I have them in my bedroom and I don’t know what to do with them. I don’t know whether to auction them again or what?

“We got amazing support for John.”

Sonia’s life is based in Australia now with her husband Nic and daughters Ciara and Sophie.

That’s what she talks about with Kennedy when they see each other now. It’s about the present. The glory days are in the past.

“How’s Sophie? How’s Ciara? That’s basically it. It’s not about Sonia anymore,” Kennedy points out.

And that’s what it always comes back to.

Next race.

The42 is on Instagram! Tap the button below on your phone to follow us!

Huge achievement for Touhy. A win tomorrow against Port, will put them 2nd on the ladder. At the way he’s playing, hes in line to make the All-Australian team this season.

@John Paul: I reckon he will go past the 246 total of the Legend Jim Stynes,he’s been an outstanding player for the Cars this year and he’s in their leadership group for a reason.

@John Paul: no Huge achievement for Tuohy. Why does everyone misspell this. He’s earned the correct spelling. Fair play.

@Bunny Johnson: Oh shut up complaining

Stynes is an AFL legend, very highly regarded over here. Was a gentleman too , done great work with the GAA and irish communities over here. Touhy is doing very well for himself, has adapted well and is a genuinely great player.

@rocks0769: agreed. Anyone who hasn’t seen it the RTÉ Documentary on Jim Stynes is an incredibly powerful watch. It’s on YouTube “Every Heart Beats True: The Jim Stynes Story”

@rocks0769: Tuohy. Again, why does everyone misspell this.

@5☆Fily: cheers, I haven’t seen that. Will look it up tonight.

Dont follow AFL a great deal, but i assume it is very achievable for Touhy to break Stynes’ record. Is that the case?

@Gareth Ward: Big ask, but it’s doable.

@Gareth Ward: Tuohy not Touhy.

Jim styles ????! Jim Stynes im guessing is who youre trying to write about ?!