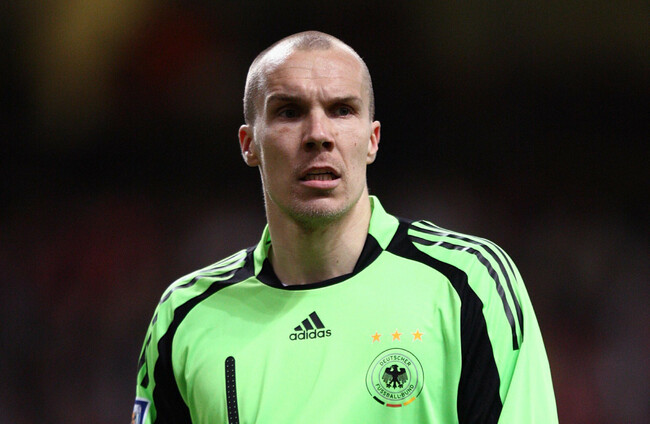

ROBERT ENKE had for a long time wanted to be the subject of a book.

Ronald Reng reported on him during the talented goalkeeper’s time as a player. In 2002, Enke signed for a relatively brief and ill-fated spell at Barcelona.

The German author and journalist happened to be living in the same city and the pair got to know one another.

During one encounter, Enke told Reng he liked one of his previous books.

“I was trying to say something, not even funny, but something clever or smart [in response],” Reng tells The42. “So just out of the blue, I said: ‘Well, one day, we’re going to write your book.’

“He took it as a serious idea.”

The journalist felt bashful in reaction to this praise and the degree of awkwardness intensified when Enke’s commitment to the project grew more apparent.

“I found out later on, he came up to me and said ‘I’m already taking notes for our book.’ I thought to myself: ‘Oh, how am I going to explain to him one day that his story is interesting but not big enough to write a book?’”

Like almost everyone in football, Reng had no idea at the time that Enke struggled with depression.

In ‘A Life Too Short,’ Reng writes: ‘Today, I know why the biography was so close to his heart. When his goalkeeping career was over, he would finally be able to talk about his illness. In our achievement-bound society a goalkeeper, the last bastion of defence, can’t be a depressive. So Robert summoned up a huge amount of strength to keep his depression secret. He locked himself away in his illness.

“So I will now have to tell his story without him.”

On 10 November 2009, the death by suicide of German international footballer Robert Enke at the age of 32 shook the world of football deeply.

He had worked with several of the sport’s most highly regarded coaches, including Jose Mourinho and Louis van Gaal, and represented some of Europe’s top clubs.

In writing the book, one of Reng’s main ambitions was to highlight that anyone, even an elite sportsperson with a seemingly enviable lifestyle, can be afflicted with depression.

“Robert was suffering from an illness that can hit anybody, whatever you do,” he says. “There are millions of people in Germany alone who suffer from depression. So we have to point out that the football didn’t make him ill. He was suffering from an illness and sometimes the football maybe was the trigger for an illness that would have come out anyway.

“That’s something that people seem to forget or not realise. They think because he was working in a high-pressure environment, he became ill from depression. But that’s not the way depression works.

“Everybody in all walks of life can be affected by depression. We had prime ministers like Winston Churchill who were suffering from depression. We also had people who work in a supermarket or sports department of a newspaper who suffer from depression. So once you’re genetically prone to depression, any kind of trauma can trigger this disease and make it break out.

“There’s one thing we should remember about Robert. His daughter died when she was two years old. Maybe that’s the worst thing that can happen to a human being, that you lose your young child. After the death of his daughter Lara, he didn’t fall into depression. So depression is not a clear-cut illness. That’s what I wanted to say — if somebody is suffering from inhuman pressure or trauma, depression can come and go whenever it suits the illness basically.

“Lots of times we don’t know why it breaks out and that’s exactly what Robert wrote into his diary when he was suffering a second clinical depression in 2009 — that depression cost him his life in the end.

“He wrote in his diary ‘why now’ because he felt at that very moment he was very happy. He had a new daughter with his wife. He was called up to play for Germany. He was having a really good season at Hannover, his club.

“So from the outside, there was no reason to become depressed. But this is an illness that, to an extent, we can’t predict and we can’t pin it down when it breaks out and when not.”

Despite the sensitivity of the subject matter, Reng experienced little difficulty in gaining access to the important figures in Enke’s life.

“I’ve written maybe 10 books and never came across people so willing to talk and to listen.

“They obviously realised that I knew more about Robert’s illness than they knew, so they were quite curious to meet me and to find out as well what happened. Almost everybody I talked to remembered Robert fondly. They were willing to pay tribute to him as well.”

Enke never went public with his depression. Almost everyone who knew him in football was unaware of his struggles.

There were tough times in Enke’s career, such as a move to Fenerbahce that ended after just one disastrous game, as recalled in the book: “After 57 minutes, the score was 3-0 to Istanbulspor. Coins, lighters and bottles flew around Robert’s ears. He knew his own fans were standing behind his goal.”

There have been instances of footballers taking time away to treat depression more recently — then-Celtic striker Leigh Griffiths, for example, did so in 2018 and received great support and compassion from the vast majority of the footballing world.

2009, however, was a somewhat different environment. The general level of understanding surrounding mental illness was not so sophisticated both in and outside of sport. So it’s hard to know for sure what the reaction would have been had Enke spoken about his troubles.

“The other thing was if the public had been prepared to accept that a sportsman was suffering from depression that he has to take a few weeks off like somebody suffering from a knee injury, and then come back,” says Reng. “I’m not sure if the public would have expected that at the time, or they would have thought he’s not apt to play in goal, he’s suffering from depression, he’s ‘not psychologically stable’.

“That might have come up in the public [discourse] at the time. But I think that’s one thing that’s definitely changed in German sport. People are much more aware that mental illnesses exist, and that suffering from depression doesn’t mean you’re psychologically unstable. It means that for a certain time, you’re not able to play football and that you can come back from that, like somebody suffering from a cruciate ligament injury.

“That understanding has been established, I think we can say, not only after Robert’s death, but because of Robert’s death, people learned that. We have several cases in German football where players were looking for treatment or having treatment for mental illnesses, and then they come back and play football again.”

The book paints a nuanced picture of Enke, conveying a vivid sense of the human being as well as the footballer.

Reng had access to Enke’s diary when writing ‘A Life Too Short,’ but was careful when it came to deciding which information to include.

He writes: “I’ve tried to pick passages out of his diaries which to my mind provide an impressive description of the illness. I have deliberately excluded passages that I see as too revealing.”

There are inevitably some incredibly harrowing and difficult-to-read passages in the book, but Reng also incorporates lighter moments and unexpected aspects to his personality, such as Enke’s proclivity for writing poetry.

“I was totally surprised that he wrote poems and I wanted to share that surprise with the audience,” Reng explains. “It’s not what you expect from your average footballer that he’s writing poems.

“I basically wanted to show Robert as the full person that he was and that part of him.

“Lots of these poems show self-irony, I think. Also, he was using these poems to deal with depression at the time. In 2009, he was with the national team alone for some international games, he was fully into his clinical depression. Teresa told him: ‘Well, try to write a poem.’ He was writing a poem quite cynically even about his condition at the time. So it was very moving to read this, but also shocking to read poems about his depression and maybe it helped people to understand a bit about his condition at the time.”

Footballers are often portrayed in the media as selfish and insensitive, however, Enke was capable of tremendous empathy.

For example, in one scene, he is outraged while watching the reaction on television to an error-prone display by 19-year-old Stuttgart goalkeeper Sven Ulreich, who has since gone on to play for Bayern Munich.

Even Ulreich’s coach, when interviewed afterwards, was heavily critical of the highly inexperienced teenager.

The veteran subsequently rang the starlet, a potential rival at club and international level, and went over his mistakes, offering him advice and expressing sympathy, in particular, owing to the coach’s harsh reaction.

Enke had gone through difficulties of his own as a young goalkeeper and perhaps saw something of himself in Ulreich, who later recalled: “I don’t think there’d ever been anything like that in professional football before, a national goalkeeper spontaneously ringing an unknown 19-year-old to help him.”

“That was the Robert I knew as a friend,” says Reng. “He cared about people and at the time, Robert could easily put himself into Ulreich’s shoes and remember how it was for him when he was 19.”

There are several other acts of altruism incorporated into the story, while Enke remains friendly with Robert’s wife Teresa, who stayed loyal to her husband throughout his struggles, with the pair’s love for one another clear despite the many challenges they faced.

“It’s been 12 years and I’m still in contact with Teresa. Maybe naturally the contact is not as fluent as it was at the time when we basically spoke on a daily basis and in the first three years [after] we spoke on a weekly basis.

“It was a kind of bonding experience — when something so tragic happens, it brings people together.”

The book was critically acclaimed, winning the prestigious William Hill Sports Book of the Year Award in 2011 among other accolades.

Reng, though, was not confident it would be so well received during the process of writing it.

“I was very insecure and asked myself: ‘What will the audience say about it?’ Will the opinion be that you were ‘basically not good enough’ to write the book? So I was a bit scared of the reaction and I was really relieved to find out that it helped a lot of people to understand depression and also a lot of people suffering from depression interestingly felt a bit more understood just by reading the book, because they realised: ‘Okay, here’s a very strong person, Germany’s best goalkeeper, Germany’s number one at the time, and even he is suffering from exactly the same fears and symptoms like I am when he’s suffering from depression.’

“What was more important than the book [was that] Robert’s wife, Teresa, was so willing to speak up in the book and later on in public and that she was prepared to do something [to address] the illness. She created the Robert Enke Foundation, which set up a network of psychiatrists that specialised in sport. So her stand really changed a lot in German football and the book was a side issue, which helped to make people understand what it means to suffer from depression.”

And for Reng, the biggest challenge was simply telling the story in as effective a manner as possible.

“I had it clear that the tone of the book had to be, I don’t want to sound negative, but very plain.

“I took a Nobel Prize winner as my role model — JM Coetzee, a South African fiction writer. ‘Disgrace’ is the title of one of his best-known books — there he writes very plainly. But immediately, the tone becomes elegant, even if it’s using very plain words. That was something I had very clear originally — I should use very simple words because the story is so strong. And if you try to use strong words, you’re exaggerating and trying too hard maybe. So I have to take myself back as a writer and let the story speak for itself.

“You shouldn’t try to express yourself as a writer through extensive language in the book, you should try to find an elegance in the simplicity. I think I was almost obsessed with the book. I wanted to know everything basically because I wanted to know for myself what had happened to him. So I needed to research extensively and speak really to everybody.

“On the other hand, you need to filter, to [ensure] that the story is not dying in too many details. So these were two guidelines for myself — try to write simple but elegant, let the story speak for itself and try to find out everything.”

Reng continues: “I was so immersed in the book, I was so obsessed to get it right, I just realised it afterwards, it was like waking up or coming back to the real world.

“I was in my world with Robert. I was writing the book in 2010 and the World Cup in South Africa was going on — the tournament which Robert would have played in. I remember I was hardly watching any games.

“There was the big semi-final between Spain and Germany, and that was basically my semi-final because I was living in Spain at the time for almost 10 years, being German, so it was my two nations playing against each other and I didn’t watch the game. I stayed in the office with Robert, writing the book that night. I didn’t care about the game.

“And I just realised afterwards when I was coming back to the real world, how bitter I had become during the process of writing, I was maybe treating other people not right because I was basically living with a dead friend for 10 months and not thinking about anything else.”

This year will be the 13th anniversary of Enke’s death. He would be 44 if he was still living today. Yet his story still resonates, particularly in the sports industry, where the tendency of athletes to speak about their problems is far more commonplace now than it was then.

“I think his legacy is, particularly [in relation to] athletes, but even everybody suffering from that illness, at least in Germany, will find better conditions to fight the illness because of Robert’s death.

“Lots of times in history, something bad has to happen for something good to come out of it. I think that’s the case. His death will always be senseless. I would obviously give everything for him to still be here, but we have to admit that something good has come out of it, there’s more awareness of the illness and for that reason, people [suffering] from the illness find healthier surroundings.”

‘A Life Too Short’ by Ronald Reng is published by Yellow Jersey. More info here.

Originally published at 09.00

Need help? Support is available:

- Samaritans 116 123 or email jo@samaritans.ie

- Aware 1800 80 48 48 (depression, anxiety)

- Pieta House 1800 247 247 or email mary@pieta.ie (suicide, self-harm)

- Teen-Line Ireland 1800 833 634 (for ages 13 to 19)

- Childline 1800 66 66 66 (for under 18s)

Brilliant book.

@Eamonn McLaughlin: It is. Read it nearly in one go as I couldn’t leave it down

@Eamonn McLaughlin: one of the best sport books around, brilliant read.

I’ll have to read it sometime. What a legend of the German game Robert Enke was – still not forgotten today either and often held in high acclaim with other German goalkeeping greats like Kahn, Neuer, Maier, Schumacher, and Lehmann.

Probably the most powerful sports book I have ever read.

Read the book a few years ago, terrible sad and was such a good bloke

The best sports book written IMO. Reading that brought back memories of how good it actually is. If you like your sports biographies, read this.