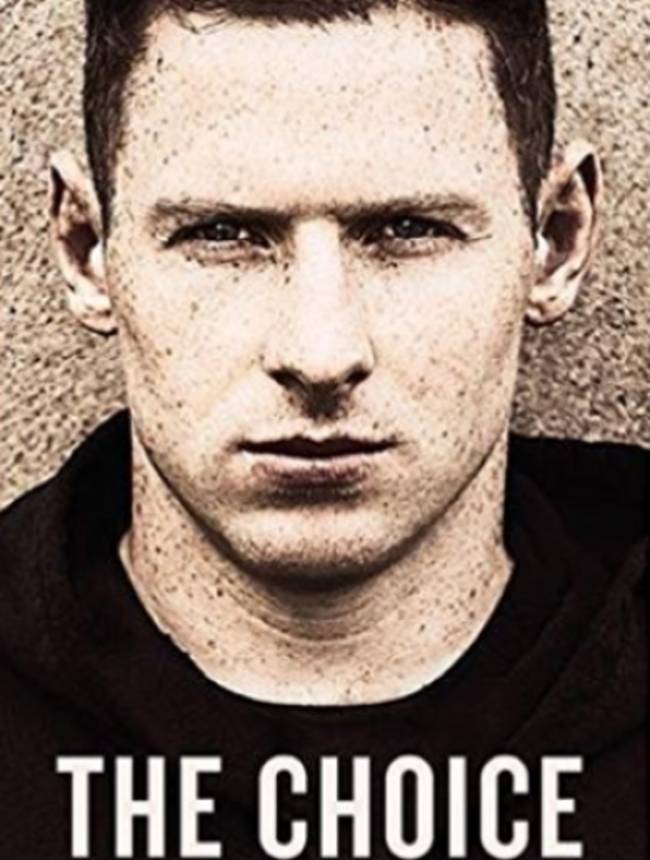

BELOW IS AN extract from The Choice by Philly McMahon with Niall Kelly.

One summer the lads decided that they were going to rob a bike – not just any old motorbike this time. A superbike. A huge gang of them went off one day to God knows where and came back a couple of hours later with this absolute beauty of a machine. It must have cost a fortune.

These lads all knew how to drive a motorbike, but I hadn’t a clue, I’d never been on one in my life. The only thing I’d ever driven was the petrol scooter that I had begged and begged Mam and Dad to get me.

I must have had them tortured over it because it cost around £400, which they definitely didn’t have spare, and they went out and bought it for me anyway. I was one of the first kids to get one in the area, certainly the first out of my group of friends, and I thought I owned the place, flying up and down the road. The noise would go through you, you’d nearly need earplugs, but I loved it.

The lads had all had their go on this big superbike and I was the last one. I got on it, after some persuasion, and I nearly killed myself. You’d wonder how I didn’t get into trouble, bombing around the field in Ballymun on a stolen motorbike, even if it was only for a minute, but I was lucky, and I was so stressed by it that I learned my lesson after that.

They got rid of the bike a little while later, sold it on — or at least, they tried to. They sent a message to another gang down the road to see if they wanted to buy it, and those lads were interested. Price agreed, deal done. They stuck one of the young lads on the bike and got him to drive it down, collect the money, and come back.

Nobody saw the very obvious flaw in this plan, but it shouldn’t have come as a surprise when the gang lifted the kid off the bike, gave him a hiding for his trouble, and sent him on his way with no money. If our lads wanted to get paid, they’d have to go looking for it. That was the start of the feud between Sillogue and Shangan.

When my friends first started taking drugs, it happened in much the same way, out of a combination of boredom, peer pressure, and a general acceptance that they had nothing much to lose by trying them. Accessibility too.

I knew all the drug dealers in Ballymun. I knew most of their names, what they sold, and who they sold to. I knew the blocks they lived in, the blocks they dealt on, and where they hid their stash. I knew where my friends got their drugs, and if I ever wanted to buy some for myself, I would have known how to get them. Everyone did.

Heroin ripped through Dublin in the 1980s and 1990s, and this place we loved was at the heart of the city’s epidemic. The veins of addiction scattered out from it and drew even more problems to us. Our homes were places where dealers could become very wealthy, and we were the ones who paid the price.

Drugs were sold all around us — in front of the flats, outside the shops, inside the shops, on the way home from school. When the 36 bus pulled up on the main road, we could spot the addicts as they got off, coming from all over the city to get their fix.

Young children knew to look out for dirty needles where they played and knew not to touch them. The stairwells of the blocks were like a revolving door, addicts going to or coming from their dealer’s flat, or worse, using right there in front of you, slumped with a syringe in their arm, so consumed that they didn’t care who noticed.

We saw the blue lights of ambulances and heard stories of people found dead from overdoses. We knew neighbours who suffered so much that they stepped off the balconies of the flats and ended their own lives.

The problem was hidden in plain sight. Occasionally — but not as often as you’d think — two or three cars would come from nowhere and pull up at the bottom of one of the towers, and the guards would pile out and into the building.

They wouldn’t have been hanging around to wait for the lift, even if by some miracle it was working, and there are enough stairs in one of those towers. A smart dealer would hear the commotion long before the guards burst through the door and, if they were lucky, would have enough time to get rid of whatever they had on them.

One of the nights after a raid, we were walking by the same block a little bit later and one of the lads stopped to bend down and pick something up. It looked like he was going to tie his shoelace, but when he stood back up, he had a little bag in his hand.

‘Lads, look at this,’ he said, waving the heroin in front of us with a smile on his face.

He had no intention of using it himself. In his mind, he’d just stumbled on a quick payday, not realising that it had been thrown out the window in a panic during the raid. We hung around the blocks for a while until he spotted one of the dealers coming down from the tower. He was over to him like a light.

‘Here, I have this,’ he said, taking the bag out of his pocket.

‘Do you want to buy it off me?’

It was gone out of his hand as quickly as it appeared.

‘Gimme that. Where the fuck did you get that? That’s mine.’

He was lucky that he got away with a few slaps. It could have been worse.

The Choice by Philly McMahon with Niall Kelly is published by Gill Books. More info here.

The42 has just published its first book, Behind The Lines, a collection of some of the year’s best sports stories. Pick up your copy in Eason’s, or order it here today (€10):

Whether you like him or hate him he’s a good lad helping his community and giving back. Interesting unlike many other sportsmen

How our guards/politicians allowed this drug infestation to take place is a crime in its self.

I remember the guards spending more time harassing the concerns parents against drugs than the drug dealers themselves.

@Chris Mc: Very true Chris; I was chair of CPAD in Ballymun in the early 80s and got arrested several times for “threatening drug dealers”! Ironically in 2013, when Philly was playing for Dublin in the All-Ireland final, a cop at Croke Park let me in for free; it was his way of apologising for arresting me for confronting a well-known dealer called Charlie O’Neill!

Got this book this morning as a present, can’t put it down, had to get dragged away from it for the Christmas dinner. It’s brilliant with a very powerful message.

I am reading this all day I nearly cried with emotion as I read the prologue what Philly felt in winning September 2011 it was the same as Dublin gaa supporters felt ..but as I read on the back story it is incredible journey for any human to walk .. Abu ath Claith

Philly has the same courage and fighting spirit as his dad who was shot by the British Army in the stomach while unarmed, escaped from British jails twice and lived in Ballymun for the last 40 years.

Like i said before is this gobshyte never off the 42

@stephen keane: It must be terrible being from outside Dublin is it ?