AT SOME point during the pandemic, Tris Dixon was clearing out his study when suddenly the memories came flooding back.

Matthew Saad Muhammad had been dead for a number of years but promptly returned to the forefront of the journalist and author’s mind.

“I stumbled across a box of stuff from my time with Matthew, the t-shirts I bought when we went to Madison Square Garden, the photos and all the clippings from the microfilms I copied in the Philadelphia library,” he tells The42.

“And I’d started to put the book together back in 2001. It was my very youthful attempt at having a crack at his life story, with all the micro cassettes of our old interviews.

“When I found this box, I was overcome by happy and sad emotions. It was a real trigger. Opening it was almost otherworldly in the sense that it dragged me right back into that period of time.”

Dixon had just come off the experience of writing the William Hill-shortlisted: ‘Damage: ‘The Untold Story of Brain Trauma in Boxing’. Though the book was acclaimed in many quarters, he describes the experience as “super stressful” owing to both the immense effort required in writing on such a difficult subject matter and the divisive reception it was met with due to its unflinching depiction of boxing’s perils.

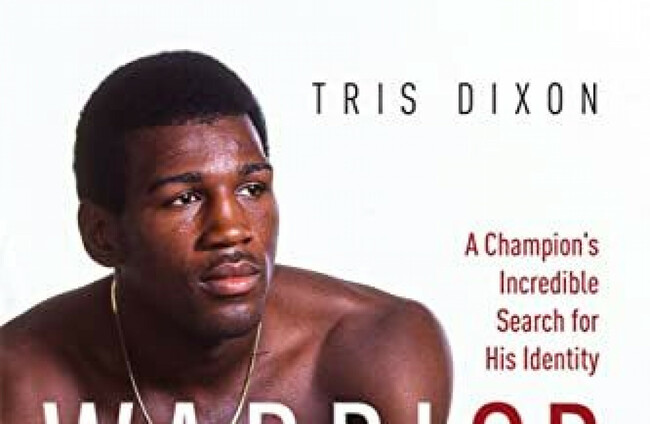

Yet once Dixon began writing ‘Warrior: A Champion’s Incredible Search for his Identity,’ he couldn’t stop. He listened back to hours of interviews between himself and Matthew and consequently, began the process of revisiting the star’s life — one that was inspiring and tragic in equal measure.

***

Dixon initially met Matthew in 2001 at an International Boxing Hall of Fame event in New York. He was young and trying to start a career as a boxer, while Matthew’s glory days were by then a distant memory.

Though Dixon’s boxing career never flourished, the pair struck up a friendship over the years, attending fights together and working on rooves for paltry money.

Matthew had agreed to do a book with Dixon, though the pair lost contact around 2007, as the former boxer became difficult to track down.

“I do remember reading the stories about him being homeless in Philadelphia and I knew there would be no way for me to reach him,” Dixon writes. “Then I read about the ALS diagnosis. I did not think it would be over so quickly.”

Their plans for the book never really got off the ground. “Turns out publishers didn’t want an unknown author to write about a forgotten fighter,” he recalls. “Neither of us were in the position to help one another with anything but friendship.”

But more recently, with several books now under his belt, Dixon was determined to finally tell Matthew’s story, even though the boxing legend was no longer around to assist in the process.

For a long time, there had even been speculation about a movie or series based on the star’s incredible life, though nothing ever came to fruition.

“The problem with Matthew’s story, and people have said it many times over the years, it’s so unbelievable that Hollywood scriptwriters would say ‘that would never happen’.

“It’s almost too far-fetched. It’s too Hollywood for Hollywood in the sense that you couldn’t make it up. There was talk that they patterned some of the ‘Rocky’ scenes on Matthew’s fights.”

Indeed, the ‘Rocky’ parallels are multiple. The foreword for the book is written by Frank Stallone — brother of Hollywood star Sylvester — and Matthew auditioned for the Clubber Lang part in Rocky III along with a number of other unsuccessful contenders, including Earnie Shavers and Joe Frazier. He also visited the brothers on the set of the 2006 film Rocky Balboa.

“I could tell Matthew was ‘shot’,” Stallone writes. “He was a little heavier, maybe 205lbs, and when I talked to him, he sounded a little slurry. But that great smile was still there.”

***

Ultimately, Matthew’s story is about an individual’s search for acceptance and validation.

This intense desire led to the ensuing extraordinary success and also was fundamental to his downfall.

At the age of just four years old, his brother Rodney abandoned him on the streets of Philadelphia. It was only after the great success he achieved as a boxer that his family re-entered the picture.

“He always wanted approval, because he’d been abandoned as a kid. So it was a big search for his identity, but it was also a search to belong,” says Dixon.

“When you look at his life, he was in the orphanage, and you’d imagine that he was trying to belong there. Then he had a foster family, and he was trying to belong there. And then he found the gym. And I guess that gave him a separate kind of camaraderie.

“And then he obviously got in with the religious ‘brothers’ and then he felt he belonged there. And he just wanted it to be included and accepted, and I think that did come from his rejection as a kid by his family. And that was probably what he was looking for his entire time. It was his entire life.”

Unsurprisingly, a series of surrogate father/brother figures emerge over the course of the narrative, from rival-fighters-turned-close-friends such as Eddie Mustafa Muhammad to the sizeable entourage that accompanied him at the height of his fame.

A significant portion of the wealth he had accumulated went towards paying lavish amounts to various members of his team and his generous nature, coupled with several bad investments and ill-advised ventures meant that by 1985, aged just 30 years old, Matthew was both burned out and bankrupt.

He found himself in this predicament despite an incredible 18-fight winning streak between 1977 and 1981, becoming the champion of the world, defending that title eight times, and being involved in six-figure purses.

The religious brothers who had persuaded Matthew to convert to Islam and change his surname from ‘Franklin’ to ‘Saad Muhammad,’ had been quick to align themselves with the star when his career was on the rise but they were conspicuously absent during the subsequent years of struggle.

Dixon explains: “What better way to be accepted than to launch your money at people left, right, and centre, and get people slapping you on the back, telling you how good you are? And I think a degree of acceptance he paid for, and obviously regretted later in life.

“In terms of a surrogate dad, he was very close with John Santos, his stepfather, the Portuguese immigrant who took him in. [His ex-wife] Michelle tells the story in the book of them going to the funeral. And Matthew actually said to her in the car: ‘I’ve got no one left. Everyone’s gone.’

“But Matthew was just a very trusting guy. When I spoke to Michelle about this, she said: ‘The fact that I had nothing was probably why he gravitated towards me, because I didn’t have anything, and I didn’t want anything.’

“‘So that was why our relationship was quite special and pure — he accepted me because he knew I wasn’t one of the guys out to take advantage of him.’”

By converting to Islam, Matthew had followed in the footsteps of Muhammad Ali, a boxer he had idolised growing up and later became friendly with.

“I speak to him about religion towards the end of the book, and he’s not religious,” says Dixon. “And I think that’s partly because the guys that sold him the dream of religion were the same guys that ultimately took advantage of him. And that was a huge regret for him later in life.”

But while Matthew may have been naive and “soft-hearted” in letting many people exploit his kindness, he also was a remarkably resilient individual.

Growing up, the Philadelphia native was bullied by other kids and ultimately became involved in gang life, which led to a spell in prison.

Amid that somewhat unlikely environment, he diligently honed his craft and paved the way for the stardom that was to come.

“Matthew told me this story about him wrapping his hands in bedsheets and putting the mattress up against the wall, and doing Ali’s moves around his cell and stuff. And then later, Salim El-Amin, one of his friends told me he was in the prison at the same time, and he remembered hearing Matthew down the corridor doing this stuff in his cell at night.

“Prison doesn’t necessarily heal or rehabilitate everyone. But Matthew was in there realising: ‘I can’t do this with my life, there’s got to be more than this.’ And that was definitely when he turned the corner.”

Matthew was best known as a fighter for his amazing ability to withstand punishment and come back from seemingly impossible positions to win grueling bouts.

“It seemed like almost every fight, he came back from the brink where there were cuts where his nose was split in half or, huge cuts over and under both eyes or where he had apparently been knocked out clean, only to regain his senses on the deck and come back and knock someone out. He just seemed to be fighting on a cliff edge the entire time.

“You have to wonder: ‘How does someone have that will to win and that courage and that desire? And I think, again, it probably goes back to looking for acceptance.

“He emptied the tank every time because he wanted people to love him. And I think he did like the identity of being a warrior. I’m not sure he necessarily thrived in it, but he was certainly very proud of it.”

This approach worked remarkably well until it didn’t. There is a widespread feeling Matthew was never the same after losing his title to Dwight Muhammad Qawi (previously known as Dwight Braxton) in December 1981.

He lost the rematch to Qawi as well and went on to taste defeat in 11 of his remaining 18 fights, suffering a series of increasingly humiliating losses against obscure boxers who would barely have tested Matthew at his peak.

The fading star eventually hung up his gloves for good following another unsuccessful bout against Jason Waller in 1992, but the decision was long overdue in most people’s eyes.

“That period from ’77 until losing the title at the end of ’81 [was incredible] And it’s not just the run, but the light heavyweight division was as hot as it’s ever been. There were superb fighters around the world. There was Víctor Galíndez from Argentina, John Conteh from England, there was Yaqui López from the West Coast, Eddie Mustafa from the East Coast, Marvin Johnson from Indianapolis.

“You could fill the top 10 with 20 fighters. It was an incredible era and he was right at the very top.

“His team held close the fact that he was overweight on the day of the fight [against Qawi] and distracted in training camp. But I think you can only go to the well so many times, and everyone knew that the wheels were going to fall off at some point. And that’s when they came off.”

Even some of those around him were urging Matthew to retire as early as the Qawi loss, but the amazing self-belief that elevated him to the top of the sport soon became a hindrance as he ill-advisedly chose to prolong his career for another decade dominated by dejection.

“I don’t think you can hold his advisors responsible because once it became apparent that he lost to Eric Winbush and Willie Edwards, they realised the well had run dry, and pretty much everyone jumped ship,” says Dixon. “He had gone from making several hundred thousand for a fight to about 30 grand, there wasn’t the money to pay a team of 15 people.

“The plainest way I could explain it is he wasn’t a skilled guy, he wasn’t an educated guy. And if someone offers him two grand to fight: how many days are you going to have to work in a labouring job to make two grand?

“And that was the only real option for him, to keep fighting. And I think he did so against the wishes of plenty of people — Michelle and others in his family tried to pull the plug. [Former boxing referee and athletic control board commissioner] Larry Hazzard in New Jersey tried to pull the plug.

“But the problem with boxing is there are so many loopholes that you can just slip through the cracks and go and fight in another minor state somewhere.

“And not only that, but someone will think: ‘Oh, wow, I either get to either train or promote the former light heavyweight champion of the world.’ And they try to pad out their own CV by using these fallen legends, which means that there’s always someone trying to bleed a few more drops of money out of these guys.

“I’m not sure how many people really sought to use him, but once he was looking for work, he could find it in the most unlikely places, be it Germany, Marbella, Trinidad and Tobago, or wherever else he would wind up.”

It was consequently no surprise that Matthew began to show obvious signs of cognitive decline long before his death at the age of 59 in 2014.

“When we were friends from 2001 to 2007, there wasn’t any education about CTE or anything, and it’s not great now. But he wouldn’t have known really what was to blame for his decline.

“One of the things that he keeps coming up in the book is when he’s young, and at the top of his game, he’s saying: ‘I want to get out before I get punch drunk.’

“And that was a repeated theme for a year or two when he was at the height of his powers. And obviously, that becomes very poignant, as you read about his [deterioration].”

Dixon continues: “When his day-to-day life became a real struggle, I said to him: ‘Do you have any regrets?’ And he said: ‘I wish I’d been an actor or a singer because then things wouldn’t be like this.’ And I don’t know necessarily what he meant by that but I did factor in the health side of it.

“I also asked him that same question at a Hall of Fame event once with hordes of people after his picture and autograph, and he’s like: ‘No, I wouldn’t change a thing.’

“So there were times when he was alone and quiet, where he just wondered: ‘Is this what life is?’ And then there were other times where people would pat him on the back for everything that he achieved, and he was like: ‘I feel like a somebody again.’”

However, such joy was only fleeting and Matthew’s multiple health issues were compounded by a diabolical denouement. He spent his final days largely living in a Philadelphia homeless shelter, often wandering the streets and likely wondering how he had succumbed to this awful form of existence.

For the second time, he had been abandoned by many of those who had claimed to love him. And in a way, his life was a series of abandonments. The miracle is that he still retained the optimism to invariably place his faith in people.

“One of the most poignant things that Michelle told me about was how she realised that the family he’d been looking for [since the childhood abandonment] were after money. They didn’t really have any interest in what he was like as a person or want to necessarily be reunited with him for the type of person he was. That was almost as bad as the first abandonment, in the sense that he felt so alone.”

Perhaps the ultimate validation would have been the much-discussed movie that never came to fruition.

“I think he thought he would be a Jake LaMotta type, where the story goes out to Hollywood, you have a massive superstar play you in the lead role, and then you live on the gravy train happily ever after. And obviously, the call never came.”

Mike Tyson was among those to pay tribute when Matthew’s death was announced, though he was hardly afforded the send-off that his legacy deserved.

“Russell Peltz, Matthew’s old promoter, was at the funeral. He said there wasn’t one active Philadelphia boxer present to pay his respects,” recalls Dixon.

This anecdote ties in with the feeling that for all his achievements and despite widely being considered one of the all-time greats by boxing aficionados, Matthew remains underappreciated to a degree.

“It’d be nice if he was known to a wider public than the boxing hardcore because his story does cross over and that’s why we talk about the stuff in Hollywood terms, right?” Dixon concludes. “This is human interest. This is cultural, it’s sporting, it’s drama, it’s everything rolled into one.”

Matthew’s life also amounts to a cautionary tale and one that is all too familiar in the world of boxing, with so many one-time greats left decrepit by the sport.

“Someone in America sent me a message saying: ‘I’ve just read Matthew’s book. And I’d love to donate to a charity that helps old fighters.’ And I said: ‘I’m sorry, there’s just nothing really set up in that respect.’ There are a few smaller charities but they certainly don’t have huge finances, reach, or resources.

“Boxing is crying out for a union to care for fighters who fall on hard times. We can predict the hard times are coming, what we need to do is prevent the hard times from coming by giving them a purpose and something to do at the point where they need to retire because too many of them have nothing else to go to.”

Yet while Mattew may have ended up abandoned by the sport and most of the people he loved, there was at least one anomaly. His ex-wife Michelle and her family continued to support the star throughout his turbulent later life and she was there at his deathbed during the former champion’s final hours on this planet.

“There was a nice line — she said: ‘I never stopped loving him and he never stopped loving me’ — you do [get the sense] it was one of those relationships really.”

‘Warrior: A Champion’s Incredible Search for his Identity’ by Tris Dixon is published by Pitch Publishing. More info here.

They will have the privilege of managing the best footballer in the country, Ashling Moloney

Was 1991 All-Ireland played in Thurles? The picture suggests so……

@John S: No, 1984 final was played in Thurles though. That’s the Munster Cup he’s holding and not Liam McCarthy

@Miguel Santychez: time to update the caption!