THERE COMES A point in the life of all columns in which the columnist stops reacting to events remote to them and instead mines their own little lives for material.

This is a) often the beginning of the end of the column – consider it the MLS/Saudi Pro League era of a column’s withering career – and b) usually happens in January, when the news is quiet.

So here’s a killer post-Christmas lede – this column has recently moved to Cork, and have you heard about these guys, Christy Ring and Roy Keane?

They still have a physical presence around the place, between the various little murals of Keane that pop up on electrical boxes on bridge corners and city streets and the statue of Ring.

Sure, there are counties to rival the richness of Cork’s sporting tradition and success but no other county – at least to the mind of this deracinated column – can claim to have made the two most consequential and totemic sporting figures in the first century of the State.

You can argue we have had greater and more successful sportspeople – and certainly some figures from our illustrious sporting past bring greater weight to bear in a medals-on-the-table competition – but Ring and Keane melded their own sporting genius with national significance.

On the face of it, Cork can be said to be virtually their only common trait.

One hurled, the other played football. One once said the best thing to be done to promote hurling would be to stick a knife in every football in the county, the other was born in the year the GAA’s Ban was lifted. One lived quietly in Ireland, the other made his fortune in England. One was reserved around team-mates, the other was his team-mates’ howling, nostril-flared backstop. One was notoriously publicity-shy in an era of minimal media, the other is ubiquitous in the mass media generation.

But while our lineage of Olympic medalists and All-Ireland winners and international footballers and rugby players have allowed us celebrate ourselves, Ring and Keane are united in standing among a tiny group of athletes who have helped us understand ourselves.

The first century of the Irish State cannot be fully understood outside of its post-colonial context, and Ring and Keane are post-colonial figures in their own way.

Let’s start with Ring, given great hurling is probably the finest sporting expression of how we like to consider ourselves. At its best it’s an independent, hectic kind of magic, where the players’ strength makes it hectic and their baffling skills make it magic.

The independence comes from the incantation you’ll hear after any great game of hurling: You wouldn’t find that anywhere else in the world.

For any idea to endure and bloom in successive generations, it needs its foundational myths, and Cu Chulainn provided one for hurling. As postcolonial critic Declan Kiberd writes in Inventing Ireland, the GAA’s founders invoking of Cu Chulainn was their own version of the muscular christianity propounded by rugby and football in Victorian England.

Ring became portrayed even during his playing days as a kind of living Cu Chulainn: a man of casual ingenuity and skill but also of enormous strength and physicality, exhibiting the kind of masculinity envisaged by the founders of the GAA.

Read surviving pieces on Ring and they will generally reference the extreme violence he had to endure from opponents, as if he withstood flows of kamikaze opponents in a manner redolent of Cu Chulainn fighting against ocean waves.

Ring proved a fine muse for two of the great mythmaking businesses of in his day – poets and American sports writers – but above all he remained stubbornly elusive. His lack of interest in meagre media coverage meant much of the country merely heard reports and rumours of his brilliance. To chime with the national experience of the time, Ring existed for many as a kind of emigrant living at home.

Keane, of course, became an emigrant: first, he might say, to Dublin for the country’s most famous FÁS course, and then to England.

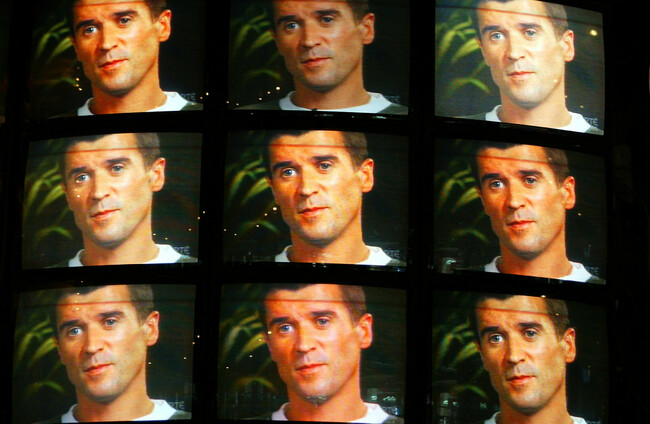

Keane thrived in England in the 1990s and early 2000s, years in which the Irish faced less official hostility than they had in earlier decades, but his sendings-off and moments of indiscipline were met with an English media still happy to indulge tropes around the hot-headed, hopelessly emotional Celt.

But Keane thrived on England’s terms, and went beyond the stereotypes. He could not have built the playing career he did on rage and attitude alone: he was as successful as he was because he was simply a brilliant midfielder. He had the passing skills, energy, and ball-winning skills of a midfielder on whom Chelsea would drop £100 million today.

If Ring gave us a means of understanding what it meant to be a great Irish sportsperson, then Keane came along to show England what it meant to be the same. If the 1990s were a decade of reshapen English attitudes to Ireland, Keane can be said to have played a role.

Other parts of Irish life can be refracted through Keane’s career. His once-complex relationship with drink is an Irish tale, and Saipan was proof of this country’s ongoing problem of finding a way to appreciate and indulge individual talent at the expense of collective uniformity. There were pieces written in Keane’s pomp of how his professionalism and demand for standards embodied the Celtic Tiger, but they of course proved to be total horseshit. Keane, unlike the architects of that disaster, was not one to give out easy credit.

With his managerial career now over, Keane is heading for the Woganzone, as he builds a successful broadcast career. Keane The Pundit doesn’t lose himself in systems and tactics and philosophies, but in being consistent on the eternal importance of the basics of attitude and professionalism, he is emerging as an enlightened voice among colleagues who either banter vapidly or tie themselves in knots trying to explain why one ideologue coach is a success and the other is a failure. The Brexit fiasco saw Ireland widely acknowledged as the adult in the room compared to their stunted neighbour, and watching Keane’s punditry sometimes conjures the same kind of feeling.

There’s one other thing that unites Ring and Keane: were they to hear of the columnist projecting all manner of national character from them, they would likely respond with mild confusion that they were simply doing their jobs.

Tommy Walsh out of retirement :)

Eddie Brennan was a lucky man to keep that gig after the Leinster U21 championship last year.

You can’t base U21 expectations off previous senior success. The majority if not all players have never had anything to do with senior level and there may be a so called “bad year” where the players in the age bracket for U21 simply aren’t good enough

There’s “simply not good enough” then there’s getting knocked out by Westmeath with players that won the Leinster minor 3 years previously. (Incidentally, Westmeath were beaten by Meath in that championship).

Jaysus Daniel….. Fair play, you’re not just a singer !

Patrick Curran was the free taker not Peter Hogan.