WHEN JIM DONNELLY died in 1959, he’d been based in the English seaside town of Morecambe for two decades. The local community were well aware of his obsession with football. As recently as six years earlier, he was still turning out for Clitheroe FC – a non-league club then plying their trade in the second division of the Lancashire Combination and based an hour away, across the lakes and fells of the sprawling Forest of Bowland.

He would’ve been 59.

At that time, he was working a construction job in Leeds and darting back to make games.

It’s difficult to know just how much the other players at Clitheroe knew about Donnelly’s life and career. They were certainly aware of his stints as a player with Accrington Stanley in the 1920s but probably knew little of his wider story. Anyway, even if they did, how much of it would they actually believe?

A fella from Ballina on the west coast of Ireland who grew up to be one of the most revered and highly-regarded coaches in European football? It sounds a little far-fetched, does it?

And that’s why the tale of Jim Donnelly is the best Irish football story you’ve never heard of.

He spent his early years on Clare Street, on the banks of the River Moy. Donnelly’s father, Edward, was a horse trainer and when the family emigrated to Sussex in the late-1890s, he took on a job as Star Groom at the newly-established Brigade of Guards Polo Club in Wimbledon Park, a private facility limited to members of the military. Unsurprisingly, given his father’s line of work, Donnelly joined the army and the onset of a world war would change the course of his life.

It wouldn’t be the last time.

“Donnelly was playing army football, which was a big thing during the war”, begins Derek O’Flaherty, researcher at the North Mayo Heritage Centre who have curated an exhibition on four local sporting heroes, whose achievements are largely unknown.

“He was recommended to Blackburn Rovers by a former winger of theirs called Alex McGhie was in the Royal Artillery. We know that from a document in which he describes the last moments of a comrade at the Battle of the Somme. So, it’s possible – though not inevitable – that Donnelly saw action in the first World War.”

His playing career was low-key, though interesting in its own right. He was in his late-twenties when signing with top-flight Blackburn (who had won championships in 1912 and 1914) in 1919 but gave them a different date of birth, cutting his age by six years. He stayed for two-and-a-half seasons before a free transfer to third-tier Accrington Stanley. A left-back, he was known for his attacking bursts, pushing past the half-backs and inside forwards, to contribute offensively – a rare and forward-thinking approach but a tactic coaches didn’t particularly encourage at the time.

There were stints with Southend and Brentford while he dropped into non-league football with the short-lived Thames AFC, based in the east-end of London, as he entered his mid-30s.

“When he was in Blackburn, Donnelly got married to Jane Isherwood and they must have moved to east London when he signed with Thames”, O’Flaherty says.

“I think they had a son because there’s a Thomas E. Donnelly born to a man called Donnelly and a woman called Isherwood in West Ham in 1930. But, unfortunately, I don’t think Thomas survived.”

As his playing career began to wind down, Donnelly started to do some coaching with the Football Association and they were sending guys to various places abroad to spread their football gospel. So, Donnelly starts off in Belgium and then it’s a bit vague until he turns up at Gradjanski in Zagreb.”

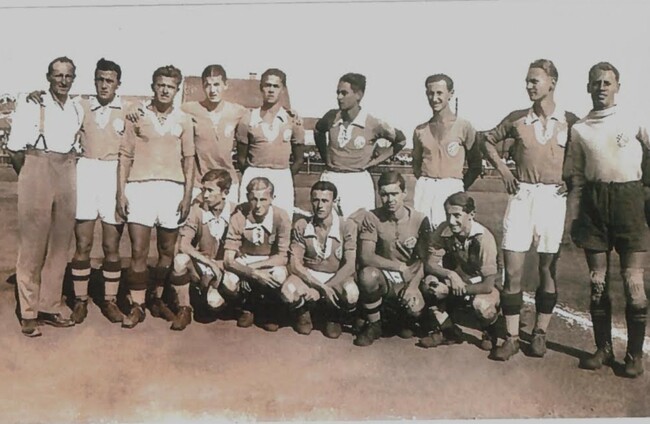

Arriving in 1933, Donnelly replaced Hungarian Gyorgy Molnar as coach. With the success of the W-M formation (3-2-2-3) in England during the latter half of the 1920s, Gradjanski – Yugoslavian champions three times in the previous 10 years – felt it was the future and wanted a technician who could implement it. Donnelly fit the bill and though he didn’t stay very long at the club – just two seasons – he certainly helped lay the groundwork for legendary coach Marton Bukovi, a huge tactical influence on the Mighty Magyars’ dominance in the 1950s and who took over at Gradjanski in 1936, guiding them to much success in subsequent years. After the war, the club was effectively banned by the new communist regime in Yugoslavia, though its successor – Dinamo Zagreb – kept the same players, the same colours and, in Bukovi, even the same coach.

Donnelly was certainly undaunted by simmering political tensions and overall social unease and clearly enjoyed his new cultural experiences in mainland Europe. In 1935, he made an arduous trek further east and settled in Istanbul to take over Gunes SK, a team that had broken away from Galatasaray and were newly-formed. The city’s other big club, Fenerbahce, were overseen by Jimmy Elliott, an Englishman who had played for Tottenham and – coincidentally – Brentford, where he had almost certainly crossed paths with Donnelly. His work at Gunes – an organisation essentially pieced together overnight – did not go unnoticed and with Turkey competing at the Olympic Games in Berlin in 1936, Donnelly was appointed the team’s coach. Many suggest he was personally asked to take on the job by Ataturk, the country’s president.

The side didn’t get far – eliminated in the first round by a strong Norway team, who would go on to claim the bronze medal. But Donnelly was part of the managerial smart set and moved in the right circles, his reputation consistently on the rise.

“We got sent a clipping from the English Football Museum from the 1936 Olympics and a guy is describing a scene in a restaurant, where a number of English coaches – all in charge of different teams at the tournament – were together”, O’Flaherty says.

“They’d obviously met up for a few pints and a bite to eat and were all in touch with each other. Now, Donnelly wasn’t there that time but his name is mentioned as having been around.”

There were a collection of British and Irish managers tasting varying degrees of success at the time, including Patrick O’Connell who’d arrived at Barcelona the year previous following his La Liga triumph with Real Betis. Considering what happened later in Donnelly’s career, it’s likely he spent some time in Berlin with Englishman Jimmy Hogan, the esteemed coach of the Austrian outfit and who’d had a seismic impact on both the country’s own Wunderteam of a few years earlier and the revolutionary Hungarian philosophy in the 50s, owing to his success with Budapest club MTK.

After Hungary’s famous 6-3 win over England at Wembley in 1953, Gusztáv Sebes was asked to explain the secret of their success.

“We played football as Jimmy Hogan taught us”, he said.

“When our football history is told, his name should be written in gold letters.”

This was the type of company Donnelly was keeping and after more success in Turkey (many claim he was in charge of the Fenerbahce team when they claimed a championship in 1937, a campaign best-remembered for a 6-1 win over Galatasaray), he was headhunted once again: this time by an Italian heavyweight.

Founded in 1908, Inter Milan had won three Serie A titles by the time Donnelly arrived at the club. But, circumstances were strange.

Firstly, under the fascist regime, Internazionale was seen as an offensive term and so the club name was changed to Ambrosiana, in honour of St. Ambrose, the patron saint of the city. But when irritated supporters kept shouting ‘Inter’ during games in protest, a compromise was reached and Ambrosiana-Inter were born.

Secondly, though Donnelly was in charge, the hostile political environment in Italy ensured the club elected to keep him in the background.

“Italy was obviously fascist under Mussolini and he used football as an important propaganda weapon”, O’Flaherty says.

“But he basically banned foreigners from playing top-flight football so the idea of a foreign coach wouldn’t have been an easy sell. The Inter ‘coach’ at the time was Armando Castelazzi and he was quite young. So my guess is that Donnelly was put in there to shepherd their new young coach who had only just retired. In any documentation – articles in newspapers or magazines – Donnelly is described as a scout, a technical advisor, a consultant, a B team coach – all sorts of things.”

“One of the interesting things about him is not just that he travelled so far but that he was in Italy in what must have been very difficult circumstances”, says O’Flaherty.

He must have been pretty self-effacing because there’s an interview with him in (Italian football publication) Il Calcio Illustrato where he talks about his football philosophy and it’s very modern sounding. He doesn’t use the phrase ‘Total Football’ but describes the Italian game as static and defensively-minded and that his belief was that you needed every player involved in the process. I think Jurgen Klopp would recognise what he’s talking about, certainly.”

Inter, with superstar striker Giuseppe Meazza finishing as the league’s top scorer with twenty goals, won their fourth Scudetto that season. Meazza would also go on to claim a second World Cup that summer, captaining an Azzurri squad that featured four of his club mates.

But by that stage, Donnelly was gone and trying to come to terms with how a monumental opportunity had been yanked from under him.

It was the spring of 1938 and with the World Cup inching ever closer, one qualified team were looking to replicate something they hadn’t had in two years.

“Jimmy Hogan had been the pioneering figure for Austria and the Wunderteam (owing to him coaching Austria Vienna in early 30s) but after the Olympics, he’d returned to England to take up a management role with Aston Villa”, O’Flaherty says.

“Up until his death in 1937, the head of the Austrian FA had been a man called Hugo Meisl, who had a really sound football brain and a great partnership with Hogan. Did they meet in Berlin in 1936? Possibly. And according to Il Calcio Illustrato, Donnelly was headhunted for the Austria job. He was probably happy to get out of Italy because it must have been a relatively scary place. Also, to win the league and get absolutely no credit for it…”

An article, from 16 March, said Donnelly was taking up the role with immediate effect.

The Austrian FA has decided to engage coach Jim Donnelly ahead of the World Championship. (Inter chairman Ferdinando) Pozzani has agreed to release the Irishman from his contract, which was due to last until the end of the season and he will take up the post without delay. Interestingly when Austria dominated European football it was Englishman, Jimmy Hogan, chosen by Austria FA chief Meisl, who coached the national team. Hogan returned to his country two seasons ago.”

For Donnelly, it was the job of a lifetime. Austria had finished fourth at the 1934 tournament and had only missed out on an Olympic gold two years later because of an extra-time Italian winner in the final.

The Italians may have won the silverware but the Austrians were revered as stylish and sophisticated practitioners. In centre forward Matthias Sindelar, Der Papierene, they had one of the finest talents the game had ever produced and, even at the age of 35, a player that was still capable of making magic.

But, for the second time in Donnelly’s life, a war changed everything.

“Before he could even get to Vienna and take over, Anschluss happened”, O’Flaherty says.

“The Nazis arrived in Austria, Jews were banned from football and the league disbanded. It’s such a tragic story.”

Sindelar only played one more game for his country, a supposed “Reconciliation Match” between Austria and Germany. The fixture was to end in a draw but Sindelar had other ideas. He’d already scored midway through the second half when team-mate Schasti Sesta made it 2-0 later on. Sindelar celebrated wildly in front of a director’s box overflowing with Nazi officials. Afterwards, he repeatedly refused to play for the German national side. His death, in January 1939, has long been the subject of conspiracy theories.

For Donnelly, the toxicity had got too much. He’d been welcomed and integrated in a variety of cities and countries around Europe. He’d been a perennial outsider, an itinerant bouncing from one fanciful location to another. But the spread of the far-right’s idealogical virus was intense and their stranglehold was squeezing opportunities. Almost overnight, Donnelly’s adventure – that had taken him from Zagreb to Milan via Istanbul and an Olympic Games in Berlin, brought him success in each location and saw him work with some of the finest players in the world – was over.

“Having given up the job in Milan and with war breaking out, Donnelly turns up again in England – along with his wife – living in her mother’s boarding house”, O’Flaherty reveals.

Then, he vanished, and slipped quietly back to real life and obscurity.

Thanks to Derek O’Flaherty, Hugh Trayer and Cagri Cobanoglu for their assistance.

The North Mayo Heritage Centre’s Lost Legends exhibition continues until the end of November. As well as Jim Donnelly’s story, three other long-forgotten athletes are remembered: baseball star Jimmy Walsh, rugby player Pat Tunney and motor racing’s Jimmy Murphy. More details here.

The42 is on Instagram! Tap the button below on your phone to follow us!

He will yea…..