JOHN GILES WAS first to rise. Sunday 13 October, 1963.

He sat alone in the breakfast area of this spit-and-polish B&B which masqueraded as a hotel, the owner/HR manager/waiter serving up sausage, rashers and egg. Even a quick read of the Sunday Press couldn’t alleviate the boredom. So up he got and off he went, round the corner to the Pro Cathedral for eight o’clock mass.

By the time he got back, the little dining room was packed, Charlie Hurley laughing at one of Noel Cantwell’s stories. Charlie was Sunderland’s talisman, brought up in Dagenham, but like Manchester United captain, Cantwell, a Cork-man. “Great old pals they were,” Giles remembers.

They all revelled in one another’s company. Cantwell, Giles and Tony Dunne had helped Manchester United win the FA Cup earlier that year, the club’s first trophy since Munich. Andy McEvoy and Mick McGrath both played for nearby Blackburn, McEvoy ending that season with 32 goals in the old First Division, two more than Denis Law managed. That season, 1963/64, Jimmy Greaves was the only player who scored more.

A fry was the sole option on the breakfast menu, Austria served up just after lunch. Three weeks earlier, in what Giles describes as ‘the miracle of Vienna’, Ireland had somehow secured a scoreless draw in the first leg of this European championship tie.

Now they were here in Dublin for the return game, still huge underdogs, but quietly buoyed by the fact the FAI’s notoriously stupid selection committee had, for once, picked a decent team. “Ah, the big five,” Giles says, smiling. “They were administrators, businessmen and none of them had a clue about football.”

They knew a thing or two about satisfying their own oversized egos, however, refusing to abandon control of selection matters for the rest of the decade. Johnny (Jackie) Carey was Ireland’s team manager in name only. “Jackie knew his stuff,” Giles says. “Unfortunately, you couldn’t say the same about the guys who picked the side.”

Hurley shared Giles’ opinion, telling the Sunday Times’ Paul Rowan in a 2016 interview that Ireland could have, and should have, matched Northern Ireland and Wales’ achievement in 1958, when both teams reached the World Cup quarter-finals. “Game after game,” Hurley says, “you would see two or three lads from the League of Ireland in our team, whom you were told were good players. But they weren’t always.”

Still, the League of Ireland boys did their best, Ronnie Whelan – father of Liverpool legend, Ronnie junior – having a particularly fine game in Vienna. Willie Browne, an amateur at Bohemians, made his debut that day. “Matt (Busby) hadn’t released Tony Dunne or Noel (Cantwell) because in those days club managers weren’t obliged to,” Giles says. “So we went with a weakened team, somehow got a draw, setting ourselves up for the return leg.

“We weren’t confident, though, because the set-up was crazy. In those days, you played for your club on a Saturday, caught the train to Hollyhead, took the midnight ferry across to Dublin, got a few hours sleep, and then you went at it again, with Ireland, the following afternoon.”

That was the timetable QPR’s Ray Brady, and Millwall’s Haverty had to follow, each of them putting in a 90-minute shift on the Saturday afternoon, Brady at Selhurst Park, Haverty at Mansfield. By coincidence they arrived at Crewe railway station around the same time to travel the rest of the way together to Hollyhead. “After a journey like that, you’d be knackered by the time you hit the bed,” Giles says.

This time they were lucky. Eight of the starting X1 didn’t have a club game the day before, just two of the outfield players, and Alan Kelly, the goalkeeper, forced into the double-weekend shift. “When I talk about that era – even though they were great times for me on a personal level– these, in fact, were the bad old days of Irish football,” Giles says.

“The selection committee were out of their depth; the fact we regularly had to play twice in 24 hours was madness and that’s before we mention how awkward the English club managers used to be. If they said no, that was it. You didn’t play.

“So, to put it in a nutshell, the whole set-up was chaotic. No planning existed. We had great players, Noel Cantwell, Charlie Hurley, Alan Kelly, Andy McEvoy, Joe Haverty – and we had the capacity to do a lot better than we actually did but because of the structure, we were going nowhere.”

But this time they went on a bit of a journey. Iceland were their preliminary round opponents, beaten 5-3 on aggregate. Next came Austria, World Cup semi-finalists nine years earlier, held in high regard in 1963.

Eoin Hand certainly thought so. He turned 17 that year, had just been signed by Drumcondra, his local club, and was earning enough to buy himself a Honda 50. “Thought I was the bees-knees,” he says.

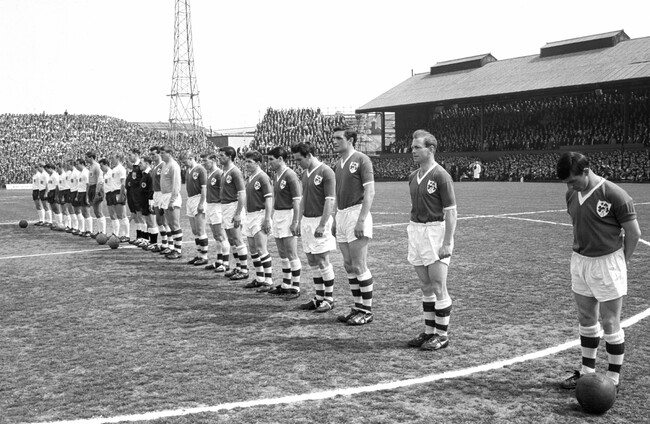

Still, getting to Dalymount Park from Iona Road, his mother’s place, didn’t require any transport. Fifteen minutes it took him to complete the door-to-door journey, along with a couple of neighbours, 39,960 others joining them. “The thing is there were so few internationals in those days, maybe just a couple in Dublin each year,” Hand, a future Ireland player and manager, said. “And these men – Giles, Cantwell, Hurley – were just giants in our eyes. You’d only ever see them in newspapers. Now they were here, in front of you. They were like pop stars to us, heroes.”

Two things strike you about the footage on the Pathé news reel; firstly the quality of Haverty’s wing-play, secondly the disregard for health and safety in 1963 Ireland. Quite how they allowed nearly 40,000 into Dalymount is beyond belief. “A lot of people in Ireland feel football didn’t start in Ireland until Big Jack steered us to Euro 88,” Giles says. “But there was always huge interest in the sport. That crowd of 40,000 for the Austria game, that was the norm.”

They certainly got their money’s worth. “Austria ’63 is still fresh in my memory,” Hand says. “Yes, it was a new competition – just the second edition of the European Championships – but it had meaning. I remember the anticipation heading to that game, the hordes at Doyle’s Corner, the pedestrians spilling onto the road by St Peter’s church because the pavements were packed.

“I even remember exactly where I stood, across from the main stand, near the back of the terrace because by 1963 I was tall enough to see over fellas’ heads. The further back you were, the better because what used to happen was crass, these geezers coming in from the boozer, just before kick-off, all steamed up. The match would start and then inevitably, about 15 minutes in, one of them would …….

“It’s disgusting to even tell this story. But it happened game after game. Fellas wouldn’t go to the toilets. If they needed a p**s, they just did it on the terrace. You’d get it on the back of your leg. Ah, stop. It was disgraceful. You’d be drenched.”

On this day, Hand’s trousers escaped. And so did Ireland, an own goal sandwiched in between Cantwell’s two strikes, Ireland’s 3-2 win secured by a last minute penalty. “The pitch invasions that followed each Irish goal just highlighted how much the game meant to us,” Hand says. Hurley excelled, so too Giles and Ireland, for the first time in their history, had reached the quarter-finals of a major tournament.

Time moves on. A quarter of a century later another Ireland team reaches the last eight of the Euros. But this time it’s different. The FAI are still a shambles but at least they allow Jack Charlton pick the team. Euro 88 goes down in folklore, followed by Italia 90, to the extent that 30 years on, a two-part documentary is shown on RTÉ to commemorate the achievement.

Yet as Giles points out, football existed in Ireland before then. That’s why 1963 deserves a mention. What was achieved that year has been wiped from everyone’s memory even though Ireland went further in the competition than the 1962 World Cup finalists, Czechoslovakia, 1966 World Cup winners, England, as well as Portugal, Holland, Italy and Yugoslavia.

“Considering the lack of preparation, we did okay,” Giles says. “But because it was all so amateurish, we didn’t really have a belief we could go further and do better.

“It was a miracle we got as far as we did but I didn’t see it as an achievement. It certainly doesn’t compare with Jack’s or Martin (O’Neill’s) achievements in ’88 or 2016. They came through a qualification process; they won more games to get to that stage. I would never say we deserved more credit for what we did, definitely not. We knew we wouldn’t go further, because the structure didn’t allow us to.”

Their hunch was right. Spain stuffed them 7-1 in a two-legged quarter-final. The curtain fell and things would stay dark for a long time to come.

– First published 08.00, 14 March

The42 is on Instagram! Tap the button below on your phone to follow us!

So he’s not going to Newcastle then

@Richard O’Brien: Thought he was a shoe-in for Derby County. Everything he needs there too.. sorry, except the bottomless pit of money.

@An Observer: your not suggesting that the reason he’s so successful is the cash he can flash are you. The citeh fans won’t like that

@Richard O’Brien: An awful lot more to management than money. Obviously he can buy whoever he wants but then he has to handle all those huge egos, keep them happy and get them playing for the team, which I think is the secret to his success. If it was just about money Mickey Mouse could be manager.

@ger o’ dwyer: thanks for the lesson and I don’t necessarily disagree but I think it takes a better manager to be successful without the cash

@Richard O’Brien: careful now, in the spirit of the 21st century we shouldn’t take the piss out of minority groups.

Great to hear a man with extensive knowledge of the game commenting about how good a league the premiership is, a lot of haters out their saying the premier league is a joke, because only one or two teams can win it, which is not to far from the truth, but the overall competition for placing is brilliant and always throws up battles for the winners, top four, europa spots and relegation.

@Devilsavocado: I mean isn’t that the case for most of the top leagues in Europe?

@Devilsavocado: style of football lacking still. Too many foreigners. Should see if this year was a one off in terms of Europe, Spain has pretty much ruled the roost for a decade or more on the club and international scene. Best players like Hazard still know the best gravy. Lots love the hustle n bustle of the premier league but prob know little else.

Earth to Chippy!?