BACK WHEN HE was untouchable, Tony Blair had a magnetism that pulled forces together.

He would need it as the end game of The Troubles played out. As talks that had dragged on for almost two years inched torturously by, the fresh-faced British Prime Minister had a habit of conducting his business in brisk fashion.

All political parties in Northern Ireland were around the table. There was wriggle room on the big ticket issues. The late Mo Mowlam had been his enforcer who would hug the awkwardness out of the stiffer members of Unionism, and disarm Republicans and Nationalists with her candour. Especially when she would take off her wig, casting it on the table in front of her.

“The wig irritates me, I don’t have time for messing about, we need to get this deal done, let’s get on with it boys,” she would chide men like Gerry Adams, Ian Paisley and David Trimble. Not – it almost goes without saying – the sort of boyos who would have been used to a scolding.

Mowlam got the Good Friday Agreement done. Along with Blair. Along with Bertie Aherne. Most of the credit will rightly go to John Hume though, who brought militant Republicans to the table and in turn, cannabalised his own party. You’d suspect he realised that then.

At that time, the northern public were beyond war-weary. The GAA community were pushed into direct firing line. In September 1993, responding to a series of firebomb attacks on GAA premises by the Ulster Freedom Fighters, DUP Councillor Sammy Wilson labelled the GAA as “The IRA at play.”

Just months before the document was signed, Gerry Devlin, the 36-year-old St Enda’s Glengormley manager was about to ring the doorbell at the front door of the clubhouse when some men approached, shot him four times in the head and left him to die.

The following week, The Bishop of Down and Connor, Dr Patrick Walsh spoke at his funeral.

“Those who are genuinely struggling to build peace,” he said, “To put the building blocks in place and cement them, must be even more determined than ever, in the wake of Gerry Devlin’s murder, to push ahead and ensure they do not allow the wreckers of peace to step in once more and set the agenda.”

How prophetic those words seem now, over a quarter of a century. Wilson still dominates political discourse, afforded a significant platform to further his zero-sum philosophy on politics. Among the lowlights and bloopers reel was the recent occasion, citing the importation of sausages into Northern Ireland as a valid concern for the NI Protocol.

Today, a plaque in memory of Gerry Devlin is mounted on the wall of the clubhouse with the text, ‘Ní Bheidh a Leithid Arís’; ‘There will never be his likes again.’

The wanton violence of Devlin’s death echoed that of Sean Brown, who was kidnapped in May 1997 while locking up the grounds of Bellaghy Wolfe Tones, taken away and murdered on a country lane in Randalstown.

Collusion is suspected in the case. Even as recently as December of last year, an inquest into his murder was again held up with members of the Police Service of Northern Ireland and the Ministry of Defence delaying handing over disclosure on the file. That was the 35th hearing on the case with Sean’s widow, Bridie, present at 86 years of age.

****

Legacy cases such as these are a stain on the hard-won peace of the present. The refusal to establish a South African-style Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which established what happened under apartheid, is a frustration.

There is precious gratitude that violence has ceased. Nowadays the poison and hate has largely transferred to online bots. Gaelic Games are now part of the mainstream culture of the north.

Current CEO of the Ulster Council, Brian McAvoy was the Down county board secretary for much of the 1990s, a period that brought two All-Ireland football Championships for his county.

“You might have got stopped in the cars going to training and matches. But that was during the Troubles times. Thankfully when the ceasefires came, and leading up to the Agreement, that came to an end virtually overnight,” he states now.

“But it would have been a regular occurrence in the ’70s, ’80s and ’90s. You would have been stopped and the kit bags would have been emptied and so on. It was unfortunate, but that was the way things were. It was par for the course.”

Politically, the six counties of Northern Ireland were somewhat ‘settled,’ but politicians had to learn to become statesmanlike. The transition took time.

Ceasefires came first. SDLP leader John Hume took part in secret talks with Gerry Adams. In time, former British Prime Minister John Major became involved, although he denied it at the time.

The Good Friday Agreement began its life. Assembly elections for the new Stormont Government were held in June 1998, but the Executive didn’t commence work until December 1999. For 18 months there was a shadow government.

“There was a sense around that time that you were Waiting for Godot,” recalls McAvoy.

“And then of course we got an Executive up and running in 1999 and it lasted all of two months before it was suspended (because of a lack of act on decommissioning).

“We got it back again in May 2000, but it was jumping rope with a number of smaller suspensions and then eventually the events of October 2002 with ‘Stormontgate’ and the suspension.”

It took until 2002 for the first meaningful engagement between the GAA and government to take place. In all the 25 years of the Good Friday Agreement, the period from 2002 to 2007 was a productive era.

After 2017, Stormont closed up again for three years, collapsed during the ‘Cash for Ash’ scandal. At the end of that year, the UK formally left the UK following the Brexit referendum. The Covid pandemic was another hole below the waterline.

With progress so scratchy, building relationships between a sporting body and government was a struggle.

But it cannot be said that things are not infinitely better now.

“I think by and large the GAA . . . Ok, we know what the charter is here. But by and large it has a good working relationship with people of all persuasions and politicians and local groups,” says McAvoy.

“You see that recently with the Uachtarán Tofa (Jarlath Burns), and some of the outreach stuff that he has been doing. They may not share all of our ideals or everything we do, but they do recognise the contribution we make to wider society and community life and I think that is respected across the board.”

Right up to the point that the redevelopment of Casement Park is concerned. £61 million was promised by the Executive as their contribution towards it. The projected cost in 2019 climbed from £77 million to £110 million. Cost of labour and materials has rocketed since.

The GAA at central level during Larry McCarthy’s term as President has been reluctant to address the shortfall. The Executive had shown no appetite to increase their share, and now Stormont is suspended again since Sinn Fein won the vote to nominate a First Minister and the DUP instantly withdrew.

All of that though, is politics and Realpolitik.

It’s ‘easier’ to be a GAA person in the north, McAvoy agrees, but adds that things in general are easier for everyone.

“It is a much better place. I remember the days as a young lad when you went to go to Belfast and were searched before you walked up Royal Avenue. Things like that were replicated at other times throughout the north.

“But yeah, it’s a much better place than it was. Hopefully, it will remain that way. Issues like Protocols and Brexit raise the antennae a bit, so we have to be careful but hopefully, those days are behind us.

****

FOR DAMIEN TUCKER, things were about to get a lot different with the signing of the Good Friday Agreement.

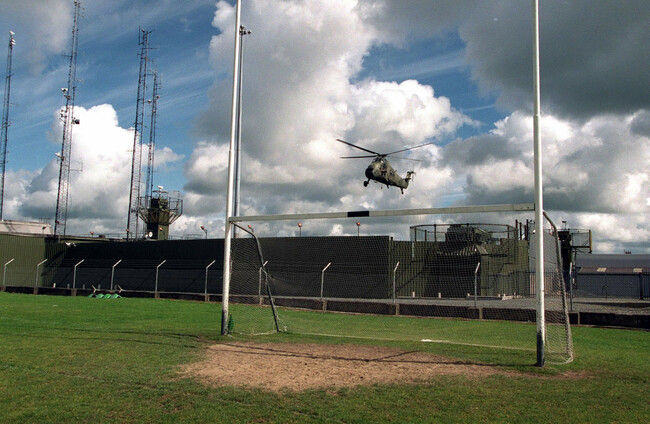

A ban on British security forces from playing Gaelic Games had stood from 1897. The partition of Ireland reinforced the belief that this was the correct course of action. In modern times, the confiscation of land belonging to Crossmaglen Rangers and harassment of GAA players only hardened attitudes.

In 1995, a Motion was included on the Clár at GAA Congress to examine the rule. It never made it as far as an actual debate.

A Special Congress was called in May 1998 at the Burlington Hotel. With strong opposition from the Ulster Council, it was agreed to let things settle in the north and park the issue.

Just two weeks after the establishment of the PSNI, in November 2001, another Special Congress was called, this time in CityWest. The President at the time was the late Sean McCague of Monaghan, who was personally in favour of lifting the ban.

From the six counties, only Down voted to lift the ban, but while the others raised objections, they also conceded that the political foundations were shifting. A poll taken of Northern Nationalists found that 57% were in favour of lifting it.

The vote was taken. Rule 21 was deleted, and McCague carried onto the next item on the Clár, steering clear of any speeches, just another housekeeping matter to take care of.

The moment was significant for Tucker.

He grew up playing Gaelic football for Tullylish, a small but significant club outside Banbridge that also produced James McCartan.

Instead of attending school in Newry and the Gaelic football cradles of St Colman’s or Abbey CBS, Tucker instead went to the largely but not exclusively Protestant school of Banbridge Academy. Being handy at rugby served him well and he formed his own attitudes on those playing and studying alongside him.

At the ripe age of 38, he would once again have an opportunity to play Gaelic football under the newly-formed PSNI team. He became a founding member of the club. The team’s trainer was Brian McCargo, a former Antrim footballer from the partisan Nationalist area of Ardoyne in north Belfast who joined the RUC in 1969.

On October 2002, the PSNI team ran out onto the pitch in Westmanstown in Dublin to play a Garda team. Tucker fielded, togged out in a green and blue kit.

Hopes that the PSNI team might be ‘normalised’ and enter a county league never came to pass. Instead, they had to be creative and take whatever options were achievable. The Ulster-Firm competition, a series of midweek games among workforces became their reliable outlet but after several years, it fizzled out due to demands of club players and unavailability of pitches.

“Certainly at the start there was a lot of publicity in 2002,” says Tucker.

“I was taking a lot of phonecalls from different people looking for challenge matches.

“Different bodies too, for example we had one with UCD. We had another game against the Law Society in Dublin. We had the odd match with clubs as well, St Brigid’s being the first one and it was well publicised.”

They aren’t the most active group in terms of games, but a lot of that can attributed to the nature of the job too.

“In terms of the GAA club itself, the ideal scenario would have been something similar to the Garda GAA Club in Dublin where they would have been integrated into the local Dublin leagues,” Tucker explains.

“Now, there were difficulties with us doing that in terms of player numbers for a start. Because of the nature of the job, you need people to get off for matches and you would have needed a big squad to sustain a campaign in a county league.

“And there would be a choice of where you go. You could say we are based in Belfast, but then you have the choice of two counties, Antrim and Down.

“There still would have been some residual security concerns even. There were plenty of things going on.”

He namechecks Peader Heffron. The former club player in football and hurling for Creggan Kickhams felt that after joining the PSNI, he felt unwelcome among his own. He was frozen out of teams. Eventually, he drifted away.

In January 2010, he was beginning a journey from his home towards Belfast to work. A car bomb planted by dissident republicans detonated, half a mile into his journey. He lost his right leg and was left with horrifying injuries.

A fluent Irish speaker, his father was a former club player, referee and treasurer. None of that mattered against the murderous intentions at play.

The PSNI GAA club was ghettoised.

“We might have expected it to go a bit further, but the fact the club has survived and is still playing is a positive,” he says.

Their only constant has been an annual match against the Garda, for the McCarthy Cup. There is a bi-annual event they enter that includes the Garda, NYPD and the Met Police that began in 2005 and is still going strong.

The team’s survival though, is perilous. Tucker spent time doing a thesis on policing. When he joined the RUC, there were 13,000 members. The PSNI membership stands now at 8,000.

“But if you were to compare the ratio of police to population, the north compared with England, Wales,” he explains, “the numbers of police in the north should be something like 3,500 to 4,000.

“And therefore, over time, when the security situation improves there will be pressure to get the numbers towards that. So instead of recruiting, you see there are less players getting in, and the team itself is ageing.”

Last year, the team were due to compete at a tournament organised by Banbridge club Clann na Banna. Tucker has cousins playing for the club and they had a relationship from playing challenge matches with them in the past. But pressures on the club forced the withdrawal of the PSNI team.

“I didn’t read it in terms of a terrible threat of violence. It is a pity it didn’t go ahead but the way it was told to me was that it was a bit of a communication issue, people misinterpreted what went on,” says Tucker.

Anecdotal evidence around the north is that there are examples – rare, but occasional – of Policemen playing for their local club while being discreet about their occupation.

Even thriving in that environment has its’ challenges with constantly changing shift patterns.

“When I was younger, I played rugby and I played to a decent standard. But I missed a lot of training session because of shift work,” explains Tucker.

“At the same time, if you are competing with someone for a place and you are missing training sessions, then there is a normal, practical issue there.”

It would be great, he believes, for everyone to be able to play among their own local club, but he would be reasonably content that there is a place for playing with work organisations.

For Tucker, the Good Friday Agreement was never a moment in time that everything would change afterwards. Rather, it is something that requires nourishment.

“It’s a work in progress, but it is a process still ongoing.

“For me, sporting wise it was great to be able to play GAA again. I was much too old for it, but I knocked a bit of fun out of it and there was the social element there as well. And that’s normal for any sport team. For me, it was very positive.”

****

In the lead-up to the Good Friday Agreement, summers in the north were blighted by the Drumcree standoff.

The Orange Order insisted that they march what felt was the ‘traditional route’ to and from the Drumcree Church on the Sunday before the Twelfth of July. They had been doing so since 1807, when the surrounding area was mainly farmland.

However, as development grew, a significant Nationalist population came to populate the area around the Garvaghy Road. In the 1970’s and ‘80’s, the outward leg of the march along Obins Street was causing trouble. The march was then banned in 1986 from going along the area.

Attention then turned to the return leg along the Garvaghy Road. This area from 1995 to 2000 became of a war zone after local residents succeeded in stopping the march in 1995 and 1996.

Loyalist violence predictably followed, and police allowed thousands of Orangemen to proceed down the road. The two leaders of Unionism, David Trimble and Ian Paisley, travelled down the road together, hand in hand.

For 1998, the army sealed off the area with steel and concrete barriers, covered in barbed wire. Threats of Loyalist violence because of this action were not empty. On 12 July, three brothers, Jason, (9), Mark (10) and Richard (11) Quinn woke up to find their house in Ballymoney on fire. It had been petrol bombed by the Ulster Volunteer Force. All three children died.

Since 2001, things have calmed down but for a time this was the most divisive area of the north. While Drumcree was in Portadown, which adjoins Craigavon and Lurgan.

All of this was going on while Diarmuid Marsden of Clan na Gael was making his name for an Armagh team that would break on through to the other side in 2002 in winning their only All-Ireland title.

“Lurgan, I suppose would be geographically split. One side of the town was Nationalist, the other side Unionist. It’s always been that way since I can remember,” Marsden explains now.

“Now, maybe we were protected from all of that by our parents and coaches from whatever else was going on in the news and media, but you just got on with it, played away with your club and then, your county.

“But you knew not to venture too far into the other side of town, if that’s not too crude.

“And that’s how it was, and in many ways, it’s still that way. An invisible dividing line. But there wouldn’t be the same issues for young people crossing those boundaries nowadays, thankfully.”

Like many towns in the north, advertising your connection to the GAA by carrying a kitbag or wearing a jersey was inadvisable. In Lurgan, it was outright dangerous. Not now.

“They are trendy now. People enjoy wearing them and people have no problem wearing them to support their county or club, or just one that they like the look of. There doesn’t seem to be any issue for people now wearing a jersey up the town. And that’s great, because you are not offending anyone, you are just wearing clothing,” says Marsden.

Now, Marsden works as an Integration Officer with the Ulster Council. It was the foresight of the late Ulster CEO Danny Murphy to establish such a role and engage with non-GAA communities.

Rather than forcing Gaelic Games on children, instead they would host events that offered a mixture of rugby, soccer and Gaelic football or hurling.

“So when you are offering Gaelic football, soccer and rugby as a ‘Have a Go’ scenario, most schools are happy to take part in that. Now, children have an opportunity to play Gaelic Games whereas they never had before. And to add to that, you had kids growing up in a Catholic, Nationalist area who had never had the chance to play rugby before. So we make it work from both angles,” he explains.

“The response has been very, very good. We have a strong partnership with the IRFU and the IFA and through different funding schemes with staff on the ground you can roll out different schemes.

“Now, the funding for that comes through the Department of Communities, which is a new thing. There also has been money accessed through Peace money, the Department of Foreign Affairs which the target being to address issues of sectarianism and division and to promote peace and reconciliation.

“They are key areas that our staff would go, now just to deliver a session, but doing workshops about getting to know the GAA, what it is about and promoting the area of reconciliation. That has been very well received.”

Occasionally, they meet with resistance. A local Councillor might thump the odd tub to make sure their presence is noted. Some parents make complaints to school principals. But it’s just minimal.

They don’t keep data on the numbers of children playing GAA from Protestant backgrounds, or how many go to their local club after being exposed through the programmes. And the reason for that is very explicit; those that want to play GAA must be treated the same as anybody else.

The Ulster Council also run the Cuchulainns Project, where they bring together three schools together in a certain area, funded by the Stormont Executive.

“Last year we had Limavady Grammar, Limavady High, and St Mary’s Limavady. They sent interested boys in fourth year together to try out Gaelic football and hurling,” Marsden explains.

“And from that, the boys become their own team; Limavady Cuchulainns and they train over the summer period and finish up with a trip to London.

“Some of their parents may well have been reluctant for them to get involved, and some of those schools there would have been parents who wouldn’t allow their children to get involved.

“More’s the pity. But the ones that do, they go back and can feed back how it was a positive experience. That’s all we can keep doing.”

The remit of the Ulster Council is different. They deal with a different reality on the ground. They don’t get the credit for what they achieve, such as Arlene Foster attending the Ulster final in 2018. At the end of January, Secretary of State for Northern Ireland Chris Heaton-Harris attended the Dr McKenna Cup final, as has Peter Robinson and the late James Brokenshire.

Small steps, but crucial in building trust between communities.

“So these things go on,” adds Marsden.

“We don’t shout from the rooftops about them but it shows the GAA is there, moving forward and doing the best we can. With Jarlath Burns in as President, hopefully it can drive things on to another level.”

****

Forwards, into the future.

Given he wasn’t even a teenager with the Good Friday Agreement was signed, Dave McGreevy admits to seeing things a bit differently. A decade spent living and working in London, where he played for the county team, rounded out his life experiences.

“I am a HR manager for an engineering company in Belfast,” he states.

“I had to do our employment audit a while ago and I work with people, I sit next to them every day and I haven’t a clue what background they are. Because it is not how we grew up.

“I am 37 now. I find that people over the age of 40 have a different view on things.

“So to get the background of our workers, I had to do the residual method, where you look back at the school they attended, the hobbies they have and all this stuff.”

During the Covid lockdown, he and his friend Richard Maguire had a discussion around how there was no GAA club in East Belfast, a staunchly Unionist area.

On 31 May 31, 2020, they posted a Tweet asking if anybody was interested in playing for a new club in the area, could they send an email. They had hoped to get an Under-12 team out of it.

But it completely blew up. Just over six weeks later they were affiliated with the Down county board and had their first senior men’s match against St Michael’s of Magheralin. They had 130 registered players to pick a team from.

They enlisted Linda Ervine, from a Unionist family in East Belfast and prominent Irish language enthusiast, to become the club president. The club crest was designed with the famous cranes of Harland and Wolff featuring along with a thistle, a shamrock and a red hand of Ulster.

The accompanying text alongside was in English; ‘Together’, Irish; ‘Le Chéile, and Ulster Scots, ‘Thegither.’

It wasn’t all plain sailing. Some Loyalist threats followed and a pipe bomb was planted at the grounds where they trained in August. Members of the club were warned to check under their cars for bombs.

Despite that, they attracted a massive number across various backgrounds.

Usually, they might have something between half a dozen to a dozen people making contact each day, seeking to join. On the occasions when the club have featured in the media, for good or bad, that figure jumps to over 20.

“These people who would like to destroy us are our best recruiters,” he says.

“We did an anonymous survey the first year of the club. And it was 26% of respondents said they came from a Unionist background,” McGreevy explains.

“But we have opened it up to kids since then. If anything, that figure has probably grown.

“Last season we finished up with 150 men’s footballers. We have a fourth team with guys who are pretty new to the sport. I have no idea of their background. They are just one of our clubmates and nobody cares in our generation.”

Their membership in an astonishing success story. Right now, they are the biggest club in Ulster for playing members.

“Whenever we were in discussion with Ulster GAA about doing our Development Plan, that was our first season and we would have had 400 adult playing members,” states McGreevy.

“Up to this point, the biggest in Ulster was 170. That’s how big we are. It’s gone to 450 the past few seasons.

“So that’s the scale of it and people don’t appreciate it. The amount of times you would be chatting to the Council and they only really see you as one team. We are twelve different teams here and we really need a pitch!

“Since we finished our football season there last year, and this is from the final game, we had 30 new players transferring in. That’s similar to every code. It’s usually in the ladies and camogs, they have big numbers coming in all the time.”

They are out coaching in five different schools now. The schools are huge. In a single week, they might see 5,000 children in primary schools.

Here’s the jaw-dropper; only one of them is a Catholic Primary school.

You wonder though if it is a forum for conversations around politics and religion, but McGreevy laughs like a drain at the very thought.

“Nobody could care less!

“We are coming into our fourth season now and there’s been a good few engagements, a lot of relationships established, a few marriages and some kids!

“So the first wedding is going to be this year between two people that met through the club. Maybe we are bringing people together too much!

“But it’s a community. Nobody cares about politics. Absolutely nobody cares about religion.”

****

It would be nice to leave it like that. To believe deep down that the Good Friday Agreement has been a total success story.

When Dave McGreevy states that nobody cares about religion, he refers to the practice of going to Church or Chapel.

And when Diarmuid Marsden says, “you are not offending anyone, you are just wearing clothing,” it’s not that simple.

Only this week, a court in Belfast heard three 18-year-old boys were last weekend subject to a ‘vicious’ sectarian assault in Belfast city centre after one was discovered to be wearing a GAA top and was asked his religion.

It was said they struck up a friendly conversation with two men, and one of them, 36-year-old Andrew McCullough was charged with two counts of attempted grievous bodily harm with intent.

The detective investigating the attack said that one victim suffered a broken collar bone and wrist. Another tried to intervene and was also knocked over and ‘savagely kicked to the head and body.’

Based on CCTV footage of the incident, McCullough’s accomplice, currently in custody on connected charges, attempted to put one of the victims through a shop window and then threw him back onto the road.

District Judge Stephen Keown refused bail for McCullough on the grounds of risk of re-offending.

This came just merely days after the Strandtown Primary School in East Belfast were subject to a number of ‘intimidatory comments’ after their premises were hired for a taster session with East Belfast GAA.

The school subsequently have ended the scheme, with principal Victoria Hutchinson sending a message to the club saying that were, “exceptionally disappointed,” to have to end their association, feeling that it didn’t reflect the ethos of the school.

A club spokesperson said, “We would like to thank everyone within our local community for the support they have given us and continue to give us.

“For us and our academy, Gaelic games are simply about children from all sections of our community playing sport – together.”

25 years on. We’re not there yet.

Get instant updates on the Allianz Football and Hurling Leagues on The42 app. Brought to you by https://www.allianz.ie/”>Allianz Insurance, proud sponsors of the Allianz Leagues for over 30 years

Irish qualified, just saying!

@Nicholas Ryan: curious as to how?

@Aidan Prior: never stopped Ireland before.

@Aidan Prior: His granny on his dad’s side I believe. Watch the Jude Bellingham documentary on Birmingham YouTube channel. Shows young Jude himself sporting a mid-00′s Rep. of Ireland jersey with Eircom sponsor… possibly Steve Staunton management era. That being said not a hope he will play for Ireland with Jude already playing for England.