Updated at 18.36

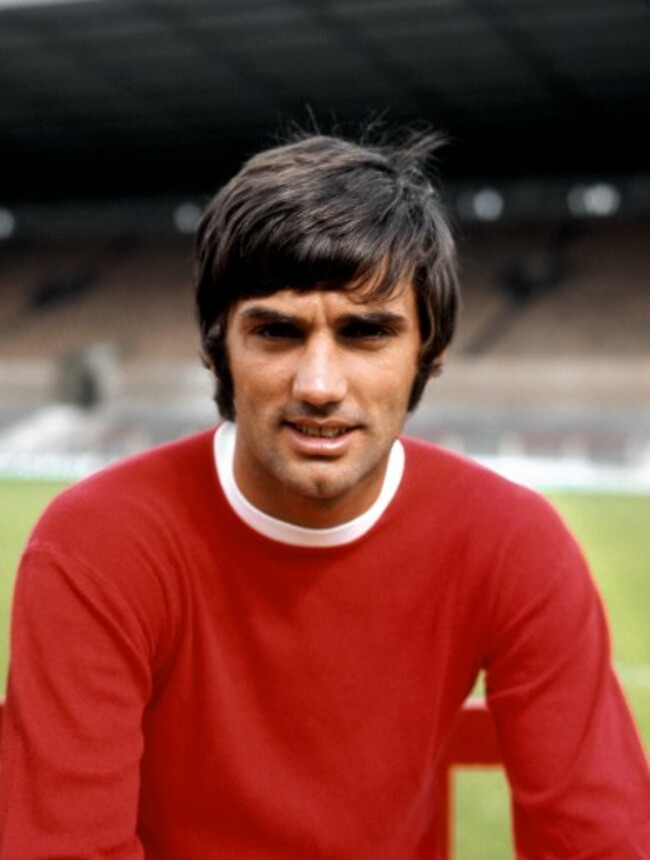

MANCHESTER UNITED LEGEND George Best — unquestionably one of the greatest players ever and arguably the first-ever footballing celebrity — has, over the years, become a cliché, a by-word for ‘cautionary tale’.

Yet the truth is naturally far more complex than this cartoonish image of him suggests, as a book by acclaimed sportswriter Duncan Hamilton explains.

One of the predominant theories of Hamilton’s biography of the star goes against the grain of common thought — namely, that George Best’s career faded fast primarily as a result of his undue love of alcohol and other forms of excess. Instead, Hamilton firmly believes that it was Best’s lack of success on the football field (when measured by his incredibly high standards) that drove him to alcohol.

“There are several myths about George — some of which he liked to push himself,” Hamilton says. “I think the biggest myth about George Best is that drink brought an end to his football career. It was the football that led him into drinking. There’s no doubt about that.

“The fact is that after 1968 and Wembley, he thought that Manchester United would be the next Real. He thought they would continue to win the European Cup. He thought they would be built around him. He thought his peak would come at 29 years old. And he thought he would carry on winning medals. Because that’s virtually what he had done every season since he’d made his debut.”

Best’s rise had been meteoric. The Northern Irish footballing legend was signed by Manchester United at 15, before making his first-team debut at 17 and scoring on only his second appearance for the club.

The player’s impact thereafter was even more phenomenal, having played a considerable role in helping United to two league titles and a European Cup by the age of 22, also claiming the Ballon d’Or and becoming the youngest-ever Footballer of the Year winner in the process.

And Hamilton was one of millions who would regularly fantasise about replicating Best’s talents on the football pitch.

“George was one of my boyhood heroes. I’d go as far as to say he was my footballing hero. I became obsessive about football for the first time in the 67/68 season. That was his absolute zenith. Manchester United finished second in the Championship, they won the European Cup and George was the Footballer of the Year. When we went outside to the park, all of us wanted to be George. There were 43 George Bests running around. You would pick up all the football magazines – Jimmy Hill’s Football Weekly or Goal or something like that. They’d just be full of George. You’d pick up any of the tabloid papers and usually find him on the front as well as the backpage. He was the person that anyone of my age latched onto.”

The decline of both Best and United was stark thereafter. He claimed to be carrying a team in which a series of new signings flopped, leading to the club’s eventual relegation and Best’s acrimonious departure in 1974, aged just 28.

He would go on to play for a number of low-profile clubs such as Stockport and Cork Celtic, but never consistently captured the form that briefly made him the best footballer in the world.

“As the United side began to disintegrate, that’s what sent him towards the bottle,” Hamilton explains.

YouTube credit: rifway22

“He was too much of a perfectionist. I think that was his problem after 68/69. He wanted to be number one. Being number two was absolutely mournful for him and being three or four — as Manchester United then were — was absolute pain. He couldn’t cope with that. He had this absolute obsession — this need to be perfect and to go and win every game.

“He said he never wanted a game to end if he was playing well. And he never wanted it to end if he was playing badly. If he was playing well, then he wanted to go and get some more goals. If he was playing badly, then he just wanted to do one thing — either score a goal or make a goal, which would send people home happy. He just couldn’t get his head around the fact that he wasn’t playing for the number one side in the country.”

And the idea that football itself, as much as alcohol, ruined George Best, is not the only highly intriguing insight in Hamilton’s book. Contrary to popular belief, not all footballers back then were earning modest amounts of cash, with Best being a prime exception to this rule.

“What surprised me [when doing research] was how much money George actually earned, because we were always told that the footballers of the 60s didn’t earn much money and they certainly didn’t in terms of salary. The most George earned as a footballer was £250, and that was in his final year at Manchester United. But from the commercial endorsements, he was the first brand footballer really. I think I’ve totalled up that between 1966 and 70, I think he put his name to 78 different things — everything from shoes to fashion to breakfast cereal to bedding. So he was earning about £100,000 a year by 1969, which was a phenomenal amount.”

He continues: “His agent kept telling him not to give his money to people, because tax was very high then, and George had a propensity to swap his sports cars every couple of months. And it got to a point where he was paying so much tax that he ended up asking to be paid in cash. And it wasn’t uncommon to find that there were five and 10 pound notes stuffed down the side of his furniture or hidden away in the sock drawer. There was someone who once went to get a clean pair of socks there and found £30,000.”

One of the reasons why his United career ended in such acrimony was owing to his tendency to pull no-shows and go missing from training for several days, instead opting to go on intensive drinking binges.

(Pat Crerand, left, and George Best, right, of Manchester United, hold the European Cup with their manager Matt Busby at Euston Station - VICTOR BOYTON/AP/Press Association Images)

Back then, the notion of media training was inconceivable and players weren’t groomed for superstardom as they are now. Consequently, the once-shy teenager from Belfast was finding his sudden celebrity status increasingly difficult to deal with.

“What else surprised me was the sheer level of fame and the unfortunate circumstances which it led to,” Hamilton recalls. “I don’t think that people appreciate that by 1970, this was a man under severe mental pressure.

“It’s why he left Manchester United in the first place. Or why he dashed off to Spain and said he wouldn’t play football. I think I’ve learned an awful lot about George as a character and I’ve tried to explain what happened to him and why it happened most of all, because everyone knows the cardinal points, but I really did want to explain why things turned out the way that they did.”

Hamilton — whose intensive research involved going through around 5,000 press clippings and 500 books, in addition to interviewing over 100 people and viewing more or less every piece of footage in which the late star appears — believes Best would not have encountered such problems were he a modern footballer.

“I think if he were playing now, the circumstances would be far different. When you look at the kind of preparation that people receive before they even get to the first team now, and even what the PFA does now for young players, it is essentially a consequence of George and his experiences. In 1965 and 66, when his fame really began to rise, no one at Manchester United really knew what was going on. And nor could you blame them for not knowing — it was just like a rollercoaster. No one could actually stop it. And no one knew what was coming next because no footballer had had the kind of attention that George had. He was so young. Even at 19, it was the equivalent now of the kind of experiences someone gets at 14 in terms of life.”

At his peak, Matt Busby oversaw Best’s development — and the legendary manager was of a different generation to the precocious Northern Irishman and very much his polar opposite in terms of personality type. And while Hamilton is reluctant to attach significant blame to Busby, he feels the manager could have done more to curb the player’s decline.

“I think he made a crucial mistake right at the start in assuming that a teenager in the 60s was the same as a teenager in the 50s. In the 50s, he’d taken Bobby Charlton to one side after he heard that he had a glass of beer before he was of a legal age to drink. But he only had to tell Bobby Charlton once. All the problems started with George in 1965, and he left him out [of the team] early in that season because he’d been spending too many nights at parties.

“He thought that that would be sufficient. And I think had he been harder at the beginning, then things might have turned out differently. But I think it’s very difficult to blame somebody like Matt Busby, because he was brought up during the Great War and he lived through the 20s and 30s. The difference between the 50s and 60s was the difference between black-and-white and colour.”

And so, given the ignominious end to his career, did Best essentially consider himself a failure for the remainder of his life?

“I don’t think so — because I don’t think he was that way inclined,” he says. “I think he always thought that he should have played for Manchester United for longer. He saw his future as being at his peak at 29 and playing for Manchester United, and actually playing well into his 30s. I don’t think he ever got over leaving Manchester United really. Nothing gave him that level of satisfaction.

YouTube credit: thecelebratedmisterk

“When he scored that famous goal for San Jose Earthquakes when he’s beating 29 men backwards, his first thought afterwards was: ‘What if I’d done that for Manchester United?’ I think that shows the kind of love and devotion he had for them.”

In many ways, Best’s career trajectory mirrored that of legendary coach Brian Clough, whose managerial style brought endless success to both Derby County and Nottingham Forest at first, yet he retired in similarly humiliating circumstances, having overseen the latter’s relegation from the Premier League.

Hamilton previously worked on a book about Clough for which he received the William Hill Sports Book of the Year accolade. So with this in mind, does he see similarities between the two characters?

“I suppose really, Brian began drinking hard in the late 80s when he was under a lot of pressure,” he explains. “And it was the same for George in the 60s. But they were different people in the sense that Brian had a very stable home life. He was very much a family man. And of course, George wasn’t. It was said that George had slept with 1,000 women before 1969. And I assumed that that figure was just one of those newspaper-talk figures. And I said to his friends: ‘what is the real figure?’ and they said: ‘well actually, probably more than that.’ So it was a conservative estimate.

“One of the interesting things is that Brian thought about signing George for Derby in about 1971 or 72, after he had his first parting from Manchester United and he said he would have sorted him out in a month. So I would have been fascinated to see whether or not that was the case. I think he probably would have handled him a bit differently. I think the first meeting might have been very sparky. And I think he probably would have got the best out of George really.”

(Manchester United’s team line up before the match: back row, l-r – David Herd, David Sadler, Alex Stepney, Pat Crerand, Shay Brennan, Brian Kidd, Francis Burns, manager Sir Matt Busby; front row, l-r – Bobby Charlton, Nobby Stiles, Denis Law, Tony Dunne, George Best)

And even though defenders have gotten fitter and modern football is vastly different from its earlier incarnations, Hamilton is adamant that Best would have excelled had he come along today, and says Lionel Messi is the one player who reminds him of the Northern Irish legend.

“I think he would flourish now with the pitches the way they are, with the tackles from behind gone, with defenders having to be a lot more careful about the way that they tackle. I think he’d be absolutely unbeatable. I think if he was in the same side as Messi, I think probably both of them could beat most sides on their own. As to what he’d be worth, if Gareth Bale is worth £85million, well £85million would probably buy George’s left leg, probably another £85million for his right leg and probably a bit more on top of that.”

And does he feel it’s still possible now for kids to idolise and obsess over star footballers, as he once did with Best as a youngster?

“I think it’s still possible. It’s a bit different — it was a bit like worshiping somebody who was on the silver screen in the 1950s and 60s. Everything’s a bit more managed now… Well, it’s totally managed. But I still see kids going up to buy albums so they can put stickers in them, so I’m sure that they’re feeling exactly the way I felt.”

YouTube credit: Darryl Rushin

‘Immortal’ by Duncan Hamilton is available to buy. Further details can be found here.

A version of this piece was originally published on 21 September 2013

Donegal Press Muff(led)

Not the first time this paper lied. Published lies regarding a Tyrone minor a few years ago

Mind games have started!