SEVEN YEARS AGO, Sinn Fein politician Pat Sheehan, who spent 55 days without food as part of the IRA’s 1981 hunger strikes, spoke to Sean O’Hagan of The Guardian about when he first arrived at the Maze Prison.

“I was feeling apprehensive, a bit scared, and half expecting a beating from the screws as a welcome,” he said.

“It seemed very quiet, then I heard someone shout in Irish, “New man on the block!” and all hell broke loose. There was cheering and shouting and men banging the pisspots on the doors. I thought, the morale is high, the lads aren’t cowed.

It was like walking out on to Croke Park to play for your county in an All-Ireland Final.”

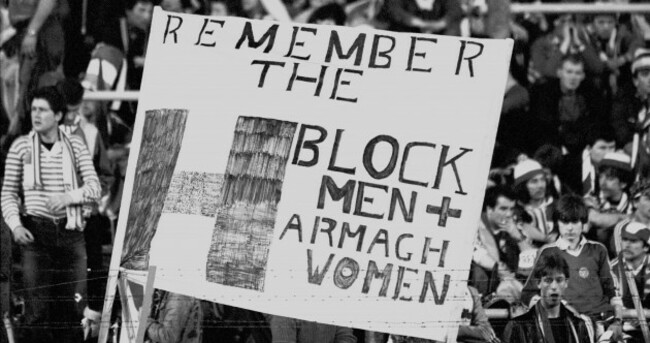

The comparison is intriguing, owing mainly to the fact that when the hunger strikes initially began, the GAA – rather inadvertently – found itself right in the middle of a traumatic and contentious political stand-off that led to massive internal division.

And that’s the topic of a presentation by GAA Museum archivist Mark Reynolds which takes place at Croke Park on Saturday.

Reynolds has spent the last decade immersed in research and, quite literally, has written the book on the subject having first made a fascinating discovery in 2007.

“When I was going through all of the files that (former GAA Director General) Liam Mulvihill left behind when he departed, I came across one that was labelled ‘H Blocks’,” he says.

“There was original material like letters from the protesting prisoners, press releases, newspaper cuttings. There was lots of unseen material. So I decided to do a Masters on the entire topic looking at the GAA and the H Block crisis from 1976 – 1981.”

Reynolds has condensed his 45,000-word opus and concentrated on a twelve-month period for the purposes of the presentation. But as much as 1981 is the harrowing final chapter, the GAA’s involvement dates back to the previous year, when IRA prisoners at Long Kesh were first contemplating hunger strikes as a protest strategy.

“The prisoners were looking for all of nationalist Ireland to come out in support of their campaign,” he says.

They saw the GAA as being integral to this. They felt if they could get the GAA on board, they’d be able to get other cultural and labour organisations on board too. Specifically, they wanted the GAA to issue a statement in support of the prisoners. They were living in their own filth for the best part of five years and the prisoners were aware the GAA was a non-political organisation so they really highlighted the humanitarian aspect. They wanted the clubs to issue statements through the press at the time that supported the protests. They wanted GAA clubs to come out and take part in the H Block marches.

Some of the highest levels of some of the county boards would’ve met with the H Block Committee – which was the support group for the prisoners – and given them their various answers. They had three or four meetings in the build-up to the 1980 hunger strike and that’s when the GAA set out their stall to say there were certain things they were able to do but there was a certain line they couldn’t cross.”

The first hunger strike began at Long Kesh on 27 October 1980. On 18 December, it was over. The prisoners had been played and none of their demands had been met. It was then that Sands knew what was needed: martyrdom. And he began planning and plotting a second, more extreme protest for the following spring.

Temporarily, the GAA had breathed a sigh of relief. The first hunger strike had passed without any casualties. In their eyes, it remained a humanitarian rather than a political issue. But, that was all about to change.

“As the protests escalated and culminated in the 1980 and 1981 hunger strikes, the GAA took the view that this was not party-political,” Reynolds says.

They said, ‘As long as the protests and whatever the clubs are doing is peaceful, it’s not against the rulebook of the GAA’. But, Bobby Sands was elected as an MP and Kieran Doherty and Paddy Agnew were elected as TDs in the Dail. In order to achieve all of that, the H Block Committee did set up a political machine. Because of that, Liam Mulvahill saw that it had crossed from something humanitarian to something political and they did intercede then. Once they started contesting against other political parties, especially in the June 1981 General Election in the south, the GAA invoked Rule 7 and said there could be no further shows of support for the H Block campaign.

While he said that and it was respected by a lot of county boards, a lot of the clubs and county boards in the north completely ignored the directive and kept supporting the H blocks – participating in the marches, putting advertising in the Irish News to outline their support for the prisoners and allowing H Block protests to take place in their grounds. So there was certainly a division there”.

Reynolds admits that it was a ‘love-hate relationship’. What the prisoners got was support from some GAA members. But, perhaps acknowledging the complexity of everything that was going on, they remained grateful for it. There was also a wider awareness that when prisoners were elected to parliament, the GAA couldn’t do much.

“At the start of the hunger strikes in 1981, there were 420 protesting prisoners,” Reynolds says.

“The H Block Committee made a big deal of the fact that 104 of them were GAA members. Some GAA clubs and county boards supported them, the highest hierarchy of the GAA didn’t really. So, on one hand, the prisoners were very satisfied with the results they got from the clubs but weren’t satisfied with what they got from Central Council or Croke Park.”

Incredibly, some of the documents Reynolds came across in 2007, included notes sent from H Block prisoners to the GAA as well as to both the Dublin and Kerry football teams, asking them for support.

“We have about 17,000 items here in the GAA Museum and if it went on fire in the morning, this is the material I’d grab first,” Reynolds admits.

There are hand-written letters from within the H Blocks to GAA clubs and to the Dublin and Kerry football teams. One is written on two rizla or rolling papers joined together and handwritten in pen and has about 200 words on it. So you can imagine how small the writing is. The other one is handwritten on toilet paper. So these explain the conditions, why the prisoners are fighting for the restoration of political status and it’s asking these teams to come out and publicly support the prisoners. From an information point of view, they’re absolutely amazing. And from an archival point of view, because of the medium, it’s fascinating to see.

There is one general letter to the GAA with over 50 signatures on and beside each one the person’s club is in brackets. So that’s one where we have personal signatures on it”.

Sands started the second hunger strike on 1 March 1981. He was elected as an MP on 9 April. He died on 5 May – the first of the protesting prisoners to do so.

Three more would die that month – Francis Hughes, Raymond McCreesh and Patsy O’Hara. Six more would die before the hunger strike finally ended in October: Joe McDonnell, Martin Hurson, Kevin Lynch, Kieran Doherty, Thomas McElwee and Michael Devine.

And through the tragedy and trauma and turbulence, there was inevitable factions within the GAA.

“There was an argument that broke out between the GAA and the guards over a proposed minute’s silence in May of that year.

Central Council issued a statement upon the death of Bobby Sands and payed respects to his family. A lot of county boards cancelled fixtures for the weekend after the death of a hunger striker. But as it went on, the H Block Committee started putting a bit of pressure on the GAA to do more. There were minute’s silences and fixture cancellations but it wasn’t appreciated by everybody in the GAA. They came in for criticism from their own members for doing it.

And there are a set of handwritten minutes from a Management Committee meeting that was called at the behest of the Ulster Council. And there’s a moment when the then-GAA president Patrick McFlynn asks the various chairmen present what they thought of the issue. And you can even see the divisions in Ulster. The three counties of Donegal, Cavan and Monaghan – there’s a bit of a lax attitude. Within the six counties, they were being ravaged on a daily basis to come out in support if the protest. For a lot of it, the GAA in the south didn’t appreciate the pressure the GAA in the north was under. So, these minutes shows the divide that existed between the 26 and the six.”

And that’s where there’s a fascinating subplot to all of this. For as much as there were vehement arguments for and against making grand statements in GAA HQ, similar contrasts existed north of the border. There still seemed a complexity to what was right and what was wrong.

“After Bobby Sands’ death, Antrim cancelled their fixtures for the weekend after that,” Reynolds says.

“But Joe Casement was the GAA correspondent for The Andersonstown News and he actually came out and said to the GAA, ‘Look, you’ve paid your respects but you shouldn’t cancel the matches because your number one priority should be Gaelic Games.’ So, some people saw the GAA as being only about the administration and promotion of Gaelic Games and nothing else.

Also at the time, people in Armagh put Crossmaglen Rangers under serious pressure to cancel games out of respect. But, as a team, as a club, they decided not to. Their reasoning was that it was what the British Army would’ve wanted. That it suited the British Army more if Crossmaglen cancelled their games. So, they played their games in defiance of what the British Army wanted. So, you had contrasting situations for various reasons.”

Mark Reynolds will present ‘The GAA and the 1981 Hunger Strike’ at Croke Park on Saturday, 1 July.

More information on the event can be found here.

The42 is on Instagram! Tap the button below on your phone to follow us!

He brought Irish hockey to a new level and I hope whoever we get in continues Ned’s fine work. I think everyone knew one of the bigger nations were going to snap him up but the timing is very disappointing for the squad with the World Cup only around the corner. Sincerely hope funding was not an issue again.

Ah jaysus, how will i sleep tonight?!

Pick up a proper stick . . Ice hockey