ENGLAND DELIVERED A tactical masterclass last Saturday night in Yokohama as they dismantled a previously red-hot New Zealand team with one of their most complete performances in recent times.

The attacking qualities of this side have evolved significantly since the appointment of Scott Wisemantel as attack coach in 2018. The former Paramatta Eel has brought a rugby league flavour to England’s attack, signified by the second-man plays that George Ford and Owen Farrell run so well.

The Ford-Farrell axis has been instrumental in creating variation to their team’s attack, with a lovely mix of utilising their power runners such as Billy Vunipola or Manu Tuilagi via the front door or facilitating their electric backs with late pullback passes behind would-be carriers.

Whilst the shape England is running is not unique, it is the execution and skill of Ford and Farrell, in particular, that is paramount to its success.

The inverted triangle

Consider a triangle hanging upside-down, the wide base at the top with the pointy end at the bottom.

A large portion of England’s attacking shape has two or three players at the base with one player at the pointy end. Let’s call it the inverted triangle, a shape frequently used in rugby league.

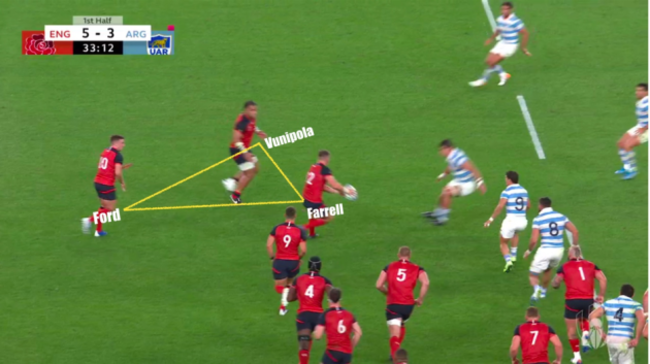

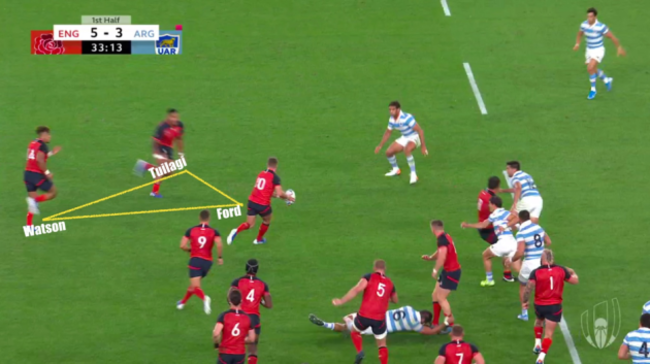

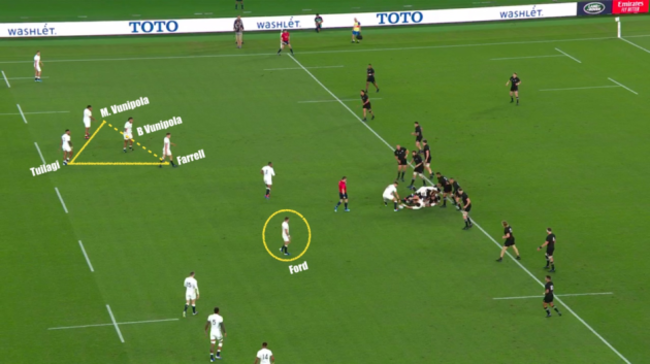

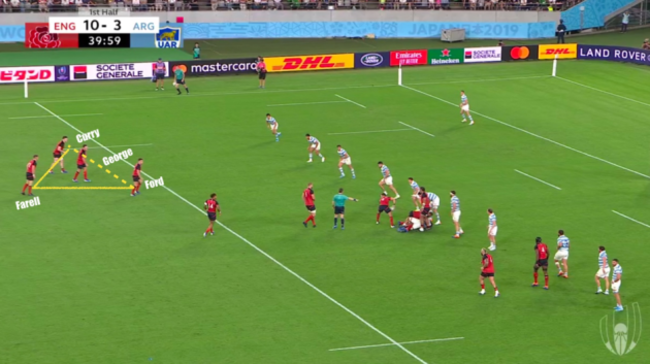

Above and below are two screenshots from a first-phase play off a lineout in England’s win against Argentina during the pool stages, which give a good visualisation of the shape.

In both graphics, there are two players at the base of the triangle with one at the pointy end.

The play hinges on the ability of the first receiver to stay square at the line and commit his opposite defender. He must be willing to ‘get dirty’ by taking the ball almost to the advantage line and drawing a tackle as he delivers the pass – leaving him vulnerable to a shipping a heavy shot in the process.

His decision on whether to play the short runner through the front door or go out the back revolves around the defender on his outside. If this defender turns his shoulders inwards on the short runner then the pass out the back is on, whereas if his shoulders turn out then the short pass will definitely facilitate a weak shoulder at a minimum for the onrushing forward.

Peripheral vision is critical for the ball player to be able to read these cues as well as keeping his hips and shoulder square so that both passes are available right until the last moment.

This skill is what sets Farrell and Ford apart from their peers. They consistently make it exceptionally difficult for defenders to make early decisions by executing the fundamentals of this play so well and so late.

Of course, what Wisemantel has cleverly leveraged is the profile of his pack and the fact that essentially all eight of his forwards are threatening ball carriers. This aids the second-man play as defenders must respect the short runners when it is the likes of Vunipola – Billy or Mako – Kyle Sinckler, Maro Itoje, Sam Underhill or even Tuilagi – who has the physical dimensions of a forward – hitting that ‘unders’ line.

In the example below, England use the triangle shape twice in the same launch, electing to use their most dominant ball carriers in Billy Vunipola and Tuilagi at the base of their triangle alongside their best ball players, Ford and Farrell, to deconstruct a ragged Argentine defence on first phase.

[Click here if you cannot view the clip above]

By having two fly-halves on the pitch, England’s attack becomes so much more fluid. Farrell and Ford interchanging between first and second receivers gives the defence different pictures to assess in a short amount of time.

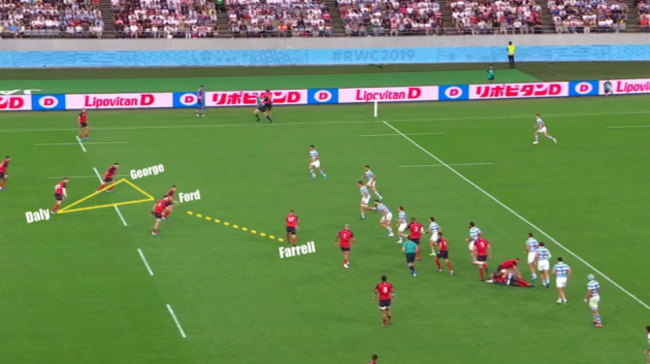

In the image below, Farrell has slotted into first receiver with Ford setting a triangle shape off him, a channel wider than perhaps what defences would be accustomed to.

As I’ve discussed, the ball player is critical to the success of the play and this time Ford possibly releases the pass to Elliot Daly a fraction early which allows the passive Pumas defence time to slide off Jamie George.

However, another layer to England’s attack has been their kicking game and Daly reads the cues exceptionally well and, as we see below, he hits a superbly weighted grubber in behind Argentina’s fullback who has closed the gate early and forces a lineout to England five metres out.

[Click here if you cannot view the clip above]

The addition of a second forward to the base of the triangle, whilst maintaining the back at the apex of the triangle, provides another layer of deception for England’s attack.

The intention of the shape is to change the picture for the defenders and create ambiguity for a split second.

A midfield breakdown, like in the above scenario, is ideal when playing with two playmakers as it facilitates the ability to attack either side of the ruck, which in turn splits defensive resources.

Ford has set to the right with three potent attackers outside him, while Farrell has England’s three-man triangle shape on his left. As New Zealand’s defence folds into position, Scott Barrett lines up opposite Farrell, Codie Taylor sets in front of Billy Vunipola and Anton Lienert-Brown picks up Mako Vunipola.

With three at the base of the triangle, England go to a slightly different shape to what we have seen in the previous examples but with a similar outcome in mind. Farrell and Billy Vunipola run a switch shape to change nomination for defenders. If Barrett chases Farrell, then the switch pass is a live option, but if he holds now Farrell is attacking Taylor with Mako Vunipola running a short line at Lienert- Brown and Tuilagi holding his feet for a pass out the back.

In this case, the All Blacks defend reasonably well, however such is the threat of Mako Vunipola on the short line, Lienert-Brown has to check slightly and turns his shoulders in which crucially Farrell sees and plays out the back to Tuilagi who in turn shifts early to Jonny May.

[Click here if you cannot view the clip above]

As we see above, the winger makes ten metres down the left edge and maintains England’s momentum on attack.

We get another example from the Argentina game below.

This time, England have both Ford and Farrell in the key playmaking positions to exploit the Puma’s defence on the edge with hooker George and flanker Tom Curry charged with holding the interior defenders.

Curry runs an exceptional unders line to literally turn Argentina’s Matias Moroni inside out.

Ford, who only has eyes for Moroni (his cue) immediately plays out the back to Farrell. Critically, the pass pushes Farrell a little wide and probably prevents a try being scored off that phase, but it still leads to a linebreak and Ben Youngs eventually scores to make it 15-3 at half-time.

[Click here if you cannot view the clip above]

This is another great example of England’s multi-faceted attack creating uncertainty within opposition defensive structures.

The other beneficial component to England’s Ford-Farrell combination is the kick variation at their disposal.

Already aided by Daly’s left foot and the excellent box kicking of scrum-half Youngs, England now have two quality tactical kickers at first and second receiver who have the ability to manage field position for their team.

This was evidenced by the possession statistics from their win against New Zealand. England enjoyed 56% compared to the All Blacks 44%, however, more significantly the vast majority of New Zealand’s possession was in their own half.

Amazingly, only 1% of the All Blacks’ attack was in the attacking 22 as England dominated the territorial battle.

Having two tactical kickers in the pivot positions makes it difficult for the defensive back three players to anticipate where the kicks might go, and tellingly last weekend England found grass on seven occasions through their kicking game.

This negated the potency of New Zealand’s counter-attack and also bought valuable seconds for their kick chase on multiple occasions.

A perfect example of this was in the 59th minute after New Zealand had just scored through Ardie Savea to make it 13-7.

From a midfield breakdown Ford, who had Farrell reloading outside him on attack, hits a perfectly angled kick over the top of replacement winger Jordie Barrett…

[Click here if you cannot view the clip above]

The utility back turns and collects after once bounce but as he shapes to kick, he gets spooked by the close proximity of Henry Slade and steps back inside where he is met with a thunderous hit by the irrepressible Underhill, who forces a turnover…

[Click here if you cannot view the clip above]

It is a huge momentum swing at a critical moment in the game as England go on to win a penalty to make it 16-6 and take a two-score lead into the closing quarter.

There have been countless examples throughout the tournament of the Ford-Farrell axis mixing up tactical kicking duties and it cannot be stressed enough how positive an impact this has on England’s attack.

By forcing opposition wingers to cover kick space on both sides of the field, it presents England’s attack with opportunities to exploit the soft edges afforded to them with their running game.

England have an impressive mix of power and skill to their game at present and the creativity of their two playmakers and their triangles are causing opposition defences a multitude of problems to try and solve.

Ford and Farrell are two men with very close links to Irish rugby, so it will be interesting to see how many Irish are in their corner this Saturday night against the Springboks.

Stunning stuff. Technique and finish was as good as you will see. All done by the PL top scorer

Don’t forget who put the ball on his foot!! Rooney!! :)

V true. Had a great game

Any chance ye have a goal we can actually see?

RVP is a class player. Delighted united signed him

Can’t see anyone challenging Utd for a few years to come.

Other than Chelsea and City I think you’re right!

Chelsea? Really? Really? Really? They are a shambles!!

And City Have the talent but not the squad debth or manager?

City have great players but they are are terrrible team. Maybe if they got jose in this summer, but if they stick with mancini they won’t go far!

Its as easy as foundation maths

CHAMPIONS 20! RUB IT UP YA

Great. Thanks for nothing.

That is such a good goal. One of the best I’ve ever seen, connects with the ball so sweetly. Last season he was my favourite player this year I despise him and the little boy inside too. But oh god how I miss him. Jealousy is a cruel cruel mistress. Well done to United. Won it in style in fairness. There’s always next season

20