The Prodigy

THE BLACK AND white photo is a little frayed at the edges, hidden deep inside a pile of sporting mementoes and yellowing newspaper cuttings, a well kept secret – until now.

If you study the picture (below) closely, it won’t take you long to spot the current Dublin manager, standing second from the right, eyes focused firmly on the photographer, wearing a collared football top and a shy smile.

Teenage prodigies are often found in places like this, scrapbooks tucked away inside a kitchen drawer, where you half-expect someone’s face to leap off the page with that before-they-were-famous look.

What took you by surprise was the sight of the other fella, the third player from the left in the back row: Kenny Cunningham, Ireland soccer captain 2003-05, a Dublin minor alongside Farrell in 1989, his teammate, classmate, friend. “When we were at school, you knew that he was one of those players whose destiny was to end up playing for Dublin,” Cunningham told me some time ago.

“Nothing could halt his progress. He was a great player then, physically strong, mentally smart. He was always a strong-willed fella, opinionated but someone who had an easy going nature, too. I’ve a lot of time for Dessie.”

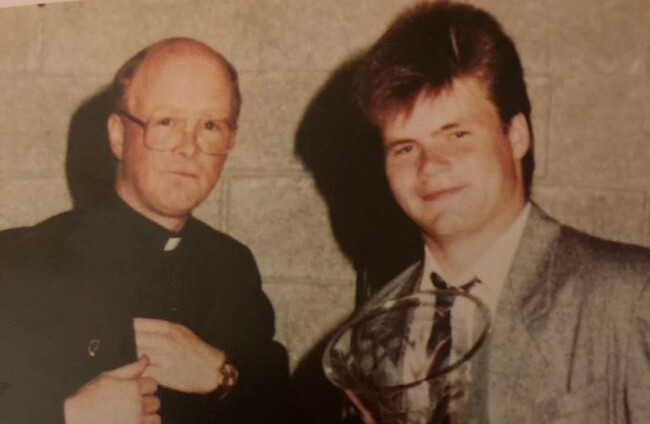

So too had his headmaster, Jimmy O’Connell, the man on the left of the photo above, who’d present Farrell with the student of the year prize at the end of that 1989 term, who’d admire the teenager’s courteous manner yet know it was the veil hiding a steely interior.

“At the time, you’d never have imagined that this boy would be Dublin manager, leading a team into an All-Ireland final,” O’Connell tells The42. “For while we knew he was going places, we wouldn’t have known where. It’s only when you look back, now that he has arrived at the destination, that you say, that makes sense. Dublin manager, yes, that fits his character. He, Kenny, were 100 per centers at everything they did, football, soccer, school. You knew they’d be a success in life. It was just a matter of what path they’d take.”

The Captain

It has been a strange old year, with a permanent shadow hanging over us, which is why today’s All-Ireland is an occasion to reflect, to consider what and who we are, the nature of belonging, the sense of place, our love of sport. For managers, winning rarely brings peace, love and harmony, just relief; but if you deliver at Croker, with the nation as your witness, well that’s as good as it gets.

He has been here before on days like this. 1992, a rookie corner-forward, hot favourites against Donegal. “We were a touch complacent,” he told me in 1999, inside the Cusack Stand dressing room, in the days when access to players was easy. You didn’t even knock on the door, you just charged in there, firing out questions as they put on their socks and stuffed their towels into gear bags.

1994, Down. “Let’s not go there.” 1995, Tyrone – his one and only All-Ireland SFC. “We thought it was the beginning.” It turned out to be the end.

Way back then, football was democratic. Farrell became Dublin captain in 1997, held that position all the way through Tommy Carr’s reign without once lifting a Leinster title. Imagine.

“Dessie was the obvious choice to become captain,” says Carr. “For starters, he had an opinion and was unafraid to express it. He was Dublin football through and through, willing to self-sacrifice for the team, not an egotist, and ultimately he had the respect of the other players. So when we made the decision, you knew there would be no one who’d say ‘why on earth are you giving the captaincy to him’? Everybody probably expected him to get it to be honest.”

Farrell understood the chain of command, accepting both responsibility and also the fact he was duty-bound to carry out someone else’s instructions. “He did not overstep his parameters,” says Carr. “Instead if he had a disagreement over something, he would say his piece, then as soon as the discussion was over, that would be that.

“He wasn’t a constant talker but when he said something, it was not for show, was always unerringly accurate and well thought out.”

That day in the Cusack Park dressing room, after Dublin had beaten Armagh in the 1999 National League semi-final, Carr’s respect for Farrell was evident. Unaware he was being watched, the then Dublin manager put a hand on his captain’s shoulder, saying just three words. “Good job today.”

That personal attachment stemmed from an emotional commitment to the same cause. “You knew you were on a tightrope because it was Dublin,” Carr says, “but you also knew you were on the tightrope together. You knew he had your back.”

It showed at the end. In 2001, Carr’s position was being voted on at county board level, delegates split on whether he should be backed or sacked.

Farrell had his own view. Ahead of the decisive meeting, Farrell and the entire Dublin panel stood outside the entrance at Parnell Park, there to show Carr their support.

“For him to do that….” Carr cuts short his own sentence. “Dessie had a bad spell personally, I don’t mind saying it because it was in the paper subsequently. He was up for drink driving. It was in the paper on the morning of the Leinster final. He came to me and said ‘I understand totally if you don’t play me’, and all that kind of stuff. Look, he was always going to play. A trust built up between us and like many things, you don’t have to say too many things about it. It is just there. It is an emotional thing particularly if you had the journey we had. We were not the best Dublin team in the world, we were in transition, but by God, did those players give it everything!”

Nineteen years on, in a week when Carr is taking a team of his own, the Westmeath Intermediate Ladies footballers, to an All-Ireland final, he thinks about his old friend coming within sight of football’s pinnacle.

“Being honest, if there were others out there standing on the line on Saturday, you’d say, ‘he does not deserve it’. But in this scenario, when it is someone you like and respect, you only want the best for him. That’s how I feel. You wouldn’t say that about everybody. But you certainly would about Dessie Farrell.”

The agent for change

He used to tell this joke against himself, how on the day he was unveiled as the GPA’s new chief executive, a little row in the Pacific kind of overshadowed things. So, within an hour of Dessie Farrell walking into office, Roy Keane was walking out of Saipan. His news barely got two paragraphs in the following day’s papers.

By the time he left, 14 years later, it was a back-page story, for by then the GPA were part of the GAA’s alphabet, the militants who’d gone mainstream.

Along the way, Farrell guided them. The initial suspicion, met by Croke Park setting up their own short-lived players body, turned to trust and by 2010, the GPA had gained formal recognition, the sporting equivalent of the Good Friday Agreement.

All the things we take for granted now; the government grants they receive, the educational and counselling support services they provide to their players, the fact the GAA/GPA name is prefixed beside the annual All Star awards, are things no one could have envisaged at the start of the century.

“In the early days, the GPA was a germ of an idea, without any formal structure to it,” says Sean Potts, Farrell’s biographer and a man who worked alongside him in the GPA for over a decade. “When it came to actually fleshing out what the GPA was going to be, it needed men like Dessie to figure out how an association could serve players in the context of an indigenous amateur sport.”

He could recognise the irony, that the GAA had professionalised itself in so many ways, rebuilding Croke Park, selling its games to television companies, taking Guinness on board as a title sponsor, paying large salaries to its administrators. “And in the middle of this were amateur players who needed direction, who needed the GPA,” says Potts.

Farrell provided that. Working initially out of his mother’s front room, he spoke to players’ organisations in America, Australia and England, connected with the European Athletes Association, secured deals with sponsors.

A campaigning body in its formative years, Farrell saw the need to develop a concept that could be acceptable to the GAA authorities, who, in turn, came to realise that the inter-county game generated the cash to allow them redistribute funds to the grass-roots.

“Dessie never feared change,” says Potts, “and people grew to trust and admire him as a person. So that helped in terms of the GPA getting official recognition and government funding. Where he really came into his own was when we sat around the table with the senior GAA officials. While he wasn’t afraid to have a row, they understood what he was hoping to achieve. The real Eureka moment came when he got the point across, to players and to the GAA hierarchy, that if a player wanted to commit to the sport at elite level, they shouldn’t do so at the expense of their own personal development. Over the years, so many players had suspended everything until their playing days were over, hoping for the best (career wise) thereafter.”

One by one, they’d then find themselves at Farrell’s door, the forgotten and the lost, realising they had paid a price for committing to the inter-county scene. “The GAA was a wonderful organisation but it was not set up back then to support its former players,” Potts says. “That is where the GPA came in. The whole concept of the GPA was to let players know that as soon as they started their journey at inter county level, the support services were there to prepare them for the sporting afterlife.”

The Manager

His own sporting afterlife was unfolding in front of our eyes. Behind the scenes, though, Farrell was developing a coaching addiction, taking his first training session in 2007, working with Ciaran Kilkenny, Jack McCaffrey in Dublin’s development squads, progressing to become the county minor manager, later their Under 21 boss.

He won and lost All-Irelands, watched as his boys matured into winners and told the media in 2016 that he had no interest in the senior job. Then Jim Gavin resigned. Bernard Brogan, Diarmuid Connolly and Jack McCaffrey walked away too, medals and history in their pockets.

A pandemic interrupted their season way more than the retirements did and by the time football resumed, Dublin looked as destructive as ever, beating Westmeath by 11 points, Laois by 22, Meath by 21, Cavan by 15.

In any other county, he’d be lauded for all that. But Dublin has more sponsorship, more funding, more players and more games in Croke Park than any other county. So the achievement of guiding a team to an All-Ireland final in his first season has been perceived as little more than a box-ticking exercise. “And that’s unfair, grossly unfair,” says Potts.

It won’t bother him, says Carr. “When you manage Dublin, you are a bit more of a target, a bit more out on your own. I won’t say you don’t care about the mudslinging, of course you do, everyone cares about things like that. But once you get your head around the fact you are just managing a football team, it can be quite simple. If you are also able to get your head around the fact you might fail, that you’ll still get up the next morning, well that helps, too. Trust me, the biggest pressure is internal.”

Especially when you remember where he’s come from, the wilderness years as captain, that League final loss in ‘99, the Leinster final defeats in ’99, 2000 and 2001.

There’s one Leinster title he won, though. Again, it’s hidden away in history’s drawer, a legacy of a forward thinking headmaster and a progressive young PE teacher who recognised their school had the potential to put together a decent soccer team.

Life has come full circle. The team in the picture was coached by John Horan, then a teacher of Farrell’s at St Vincent’s in Glasnevin, today the President of the GAA.

This evening Horan will hand Sam Maguire over to either a county who have been waiting to get their hands on it since 1951 or a former pupil of his who last held it a quarter of a century ago.

One way or another, someone’s purgatory will end.

There were many standout moments this year, many players that stepped up to the mark but for me the one player who epitomized all the good things about Leinster is Robbie Henshaw. Himself and Ringrose make Leinsters and Ireland’s best centre pairing and consistently deliver a quality of performances not matched by others either here or abroad. Long may it continue.

My wish for 2021? That we can get back to supporting our team. God I miss the RDS match days.

@Ro Molloy: so true

So if you include last seasons victories with this seasons, it something like 27 played and 26 wins. Which is an incredible stat.

@Greg Cavey: 28 out of 29 if you Champions Cup. That’s phenomenal. However they haven’t played any decent teams this yet this season. The lack of depth in most PRO14 squads makes it easy for them when the internationals are on.

Munster & Ulster are also too strong for most other PRO14 teams.

Leinster were convincing in Europe. Munster showed grit and hinted that real progress is being made. Ulster? More depth required & maybe more quality in some positions.

Playing in the PRO14 isn’t improving Leinster but maybe when the top SA teams join it will improve them & the other Irish provinces and therefore the national team.

@TL55: Why would they need to improve…They are the best in the league by far.

@Harry O’Callaghan: To beat the likes of Saracens, Exeter and Toulouse.

Leinster correctly want to the big fish in the big pond not just the little pond.

@Harry O’Callaghan: So champions cup quarter final losses are the acceptable Leinster standard now are they? Do you think Exeter aren’t looking to improve or will they just sit and wait for someone to take the champions cup and premiership from them?

@Kohn Jeenan: it’s acceptable to lose 1 game of rugby per season. This can happen if you can’t see the improvement year on year at leinster well your just not looking.

@Chris Mc: I didn’t say they aren’t improving though, they are, I was saying they definitely need to keep improving, since it was implied they don’t need to improve at all just for being the best club in the pro14….

@Chris Mc: do you not think leinster have some issues at the setpiece? Furlong should shore up the scrum but leinster still have a bit of a dependence on toner

@Tim Magner: the leinster lineout is very poor even with toner in it.

Any team who competes in the air will win a fair amount of leinster ball. Its hard to understand as Cullen was a very good lineout operator.

Its far too complicated, too many moving parts and as simple as it sounds putting toner (or Ryan) straight up at 2 often discourages teams from competing and as such makes ball to the back easier to win in the long run.

@Chris Mc: I just don’t think the leinster pack has improved since ’18. Back then they had probably the 2 best props in europe in furlong & healy, ryan was on fire, toner was 2 yrs younger, fardy was keeping lowe out of the hcup squad and leavy was at his best. Since then porter and doris have shown their mettle at international level and baird looks a serious prospect but I dont think the pack now is as good as it was

@Tim Magner: fair point, healy is not getting any younger and Jack is gone. Furlong will be back soon enough and porter is a fine prop.

Hooker we are in a better place and while Ryan is not playing as well as he was what’s coming through with baird Dunne and Moloney is getting better. The backrow is better now. Leavy is almost there and doris is firing, Conan, jvdf, connors, penny ruddock Murphy etc are all seriously pushing each other. This pack will gell over the next few months. Only real concern is at looshead.

@Chris Mc: yer by no means in a bad place, ye still have the best pack in the pro14. I think the 18 pack was the best in europe though. As you say though the 2 young hookers look the business, penny has the look of a class player and baird could be special so as a munster fan I know leinster are going nowhere

@Tim Magner: I guess time will tell with this lot. In fairness the munster pack is becoming a serious unit too. Bar kilcoyne your missing a front row but have a few younger ones who could step up but the likes of coombes JOD and Aherne all could really make the grade. Theres nothing like players who grew up wanting to play for a club.