LAST UPDATE | 26 Jun 2020

THINGS NEVER CAME easy to Curtis Fleming, but hard work and an inner drive usually got him to his desired destination eventually.

“It always came so late for me,” he tells The42.

Indeed, the defender secured a dream move to England at 22, made his Ireland debut at 27 and now, after more than a decade working in various assistant and caretaker coaching roles, at 51, he is about to embark on his first managerial job at Indian outfit Punjab FC.

The fact that he has had to go so far away from home to secure such a role is perhaps telling — in England’s top divisions, just six of the 91 managers have a Black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) background.

“If you look at the amount of BAME players that are playing in the top leagues in the UK compared to the percentage coaching, the percentage and the data doesn’t lie,” he says. “On the other hand, it’s very important that coaches like myself push young black coaches to go down the pathway, educate themselves football-wise, get as much experience as they can, so when they do get a chance to get through the door, they know what they want with experience and that they can sell their dream to the people in power.

At the moment, I don’t think there are enough coaches getting through the door and I think The Rooney Rule would help that. People keep thinking: ‘It’s a job for a black coach.’ All we’re saying is that, over the last few years, it’s been shown that there has not been many black coaches even getting an interview.

“If we don’t get the job, like everybody else that goes into a job in the world, you want transparency of ‘why I didn’t get it,’ and that will help you further down the line in your career and help you improve. Whether it’s positive or negative feedback, it’s always very good to get.”

Fleming has been a vocal anti-racism advocate for a long time — it’s 24 years since he started working with the Show Racism the Red Card organisation. He also recently attended a ‘Black Lives Matter’ protest with his three daughters near their home on Teesside.

“There’s been a real sea change. My daughters pushed to go, they asked me to go just to show support. They’re not political activists, they’re young girls. Two of my daughters are working, one in London, one in Leeds and they’re trying to make their way in life and they’re affected, it’s affecting my 15-year-old daughter who goes to school. They said to me: ‘Can we go?’ And I thought that was huge.

“I think it’s really opened people’s eyes up to the situation and gave them a chance or a reason to look at themselves and think: not, am I part of the problem, but do I really recognise it, or do I know the problem is there and don’t do anything about it?”

Fleming describes the recent events as “inspirational,” but emphasises the continuing need to educate people, warning against the dangers of complacency following the furious flurry of activity in recent weeks.

I got involved years ago through Show Racism the Red Card, because I was playing football with so many different nationalities, colours and religions. We were just working together to achieve a goal. When we came into the dressing room or ran onto the pitch on a Saturday, I wasn’t thinking I was playing with a black Brazilian guy, or a white German guy or a Slovakian or a Croatian. I was just thinking: ‘We’re all wearing the colours and we’re all going off to work.’

“It just showed that people can get along when they have a common goal and a common love for something, and football is leading the way on that.

“But there’s so much more. I think football fans are a cross-section of society. We’re giving a cross-section of society a chance to have a look and show what bonding can be, understanding other people and really educating ourselves.

“I was from Ballybough. I didn’t know I was going to be sat with a guy from Bogota, Colombia. Juninho was from Sao Paolo, Christian Ziege was from Berlin. All these different nationalities sat there sharing the information and the beliefs and the one thing that was brilliant was football, which broke down the barriers.”

Quite how the former Ireland international got to a point where he found himself playing alongside a coterie of international superstars is another, equally inspirational story.

*****

Fleming was born in Manchester to an Irish mother and Jamaican father, though he moved to Dublin when he was only a few months old.

His parents split up when he was young, with his mum Mil raising Fleming as well as his younger brother and sister.

He attended St Joseph’s in Fairview where soccer, considered a “foreign game,” was forbidden. Fleming instead played GAA, but balanced this with his preferred sport, as he played for renowned Dublin schoolboy side Belvedere between the ages of 10 and 18.

“I was the only black face in the class and in the school until my brother, Justin, who was two years younger, came in.

“So there’s no doubt, you had comments on a regular basis about the colour of your skin and you had a couple of little scuffles and pushing and bits and pieces that weren’t good. You’d be wary sometimes of walking home. You’d get: ‘You black this and you black that.’

“I lived on Tolka Road, so you’d walk from Clonliffe Road, up through Ballybough, then up over Summerhill and then you’d just duck down through Sean McDermott Street. I remember a big fella as we were walking along saying: ‘You black bastard, go back to your own country. What are you doing here?’

“And he wasn’t 24 or anything, he looked about 40. That’s my memories of it. I was only about 12. My ma wouldn’t see me all day. You’d just get your 10p and off you went for the day. They weren’t ringing you on mobiles to find out where you were, you just had to be back for dinner.

“I always think about that fella. What was he thinking? What was in his mind to say something to a young black kid? He was causing no hassle, just walking along with his mates and stuff like that. Did he know me? Did he know where I was from?

Someone said to me: ‘Sticks and stones may break my bones but names will never hurt me.’ I don’t agree with that at all. If you’re 12 and you’ve got a big man saying: ‘You black this, go back to your country,’ with that venom, don’t tell me it doesn’t take a little bit away from you and doesn’t give you fear. Yeah, he didn’t break my arm or slap me in the head, he didn’t do anything like that, but he hurt me that day. And I still remember it at 51.

“But I appreciate the childhood I had, because I loved Ballybough. My mum brought me up. I remember coming back from school and saying: ‘They called me a black bastard.’ She said: ‘I’m sorry son, I’ve got to tell you, you are black. You are black now and you’re going to be black in 100 years, so you better get used to it. It’s how you handle it. It’s not nice what people are saying to you, but you are black. You’ve got to be proud of your colour and what you are.

“She was a fantastic small Irishwoman who never took a step back and horribly, she passed away when I was 18, so we ended up having to look after ourselves. That was tough. But at the end of the day, she gave us the foundations to handle most of the things that came at you.”

Fleming agrees when it is suggested the tough blow of his losing his mum at a young age was ultimately character-building and helped provide him with the drive necessary to succeed in the Premier League.

By the time she died, he was playing in the League of Ireland with a top St Patrick’s Athletic side, while also working in retail. All of a sudden, he had to look after his younger brother and sister too.

Nobody prepares you for when your mother’s ill. Everyone thinks that their parents are bullet proof, that nothing will ever touch them, because they’re the strongest people you know and you have the most respect for. So when she went, I wasn’t thinking about paying the gas bill, or paying the electricity bill, or paying the rent. You weren’t thinking about washing and cooking and that sort of stuff. That’s not on your radar when you’re 18 and 19, or it wasn’t on mine anyway.

“I was used to playing football, seeing my mates and looking after getting in and out to work, so it definitely affected me initially. I was all over the place. What am I supposed to do here? How do you tell a 15-year-old you’re not allowed to go out, when you’re 18?

“It was tougher for my brother and sister really. I was getting a little bit older, but they were younger.

“But that was life and I was lucky that I had good family members to help me out.”

He continues: “I don’t think I was the most talented player in the world. I think I made the most of it. But one thing most people would say was that I’d always give 110%. And that determination was to never go back. I didn’t want to go back to that living. My mum had to bring up three black kids in the 60s, 70s and 80s, it wouldn’t have been easy. I always give her huge credit for her strength there.

“I would say that she suffered at times at the hands of some people. ‘Look at the black kids, what are you doing with them? Uggghhh!’ Do you know what I mean? She never really shared it with me, but I can imagine it. So I look at that and I learned from her, I learned from that situation. I learned from the people I was around. And then I just gave it the best go I could.”

During this difficult time in particular, Fleming was grateful for the guidance and support offered by manager Brian Kerr and his Pat’s team-mates, with whom he was very close.

“Brian would always be like: ‘You alright? How are you doing?’

“But the hardest time would always be when the door closes, and you go home. Maybe your brother’s out and your sister’s out. You’re sitting in the house alone thinking your ma’s not here. What am I supposed to do? How am I going to manage?

“[At Pat’s] you had Pat Fenlon, Mark Ennis, Johnny McDonnell, Damien Byrne, Mick Moody, Dave Henderson, real good fellas that you’ll speak to now and you’ll say they’re good fellas. I don’t think, whatever age they were at the time, they wouldn’t have been able to not say anything.

My mum was in St Luke’s Hospital for a few months prior to the passing. I didn’t know what St Luke’s was. I thought it was just a normal hospital, but it’s not — it’s a hospital for the dying.

“And I had to go there on a regular basis, I might have needed to go to training or I might have needed a lift or I might have had to go up and see her as she disintegrated very, very quickly.

“When she passed, I’ll always remember the lads all came in their blazers and got me out of the house to come and play. I don’t think I was great in the match. It was a home game, three days after my mam passed, but I felt like I needed to play and they were there to support me.

“But the biggest thing was after it. I’d lost the plot a little bit and I didn’t think anything else could hurt me that much. You’re on the brink of not really caring and thinking: ‘The world is a cruel place and it’s horrible. It only happens to me.’

“You need these lads to get you to training. You need these lads to give you a shout and tell you to keep going and stuff like that. I was very lucky to have a core of people that, when I look back now, were very, very important in how the rest of my career progressed.

“Have I said that many times? I probably haven’t. But now, when I sit here thinking about it, I’m thinking: ‘Wow, they got you training.’ Sometimes, you’re sat in the house feeling sorry for yourself and the worst thing in the world has happened to you. The last thing you want to do is get up and get out and go training. You need someone to grab you and give you a knock. And those lads did.”

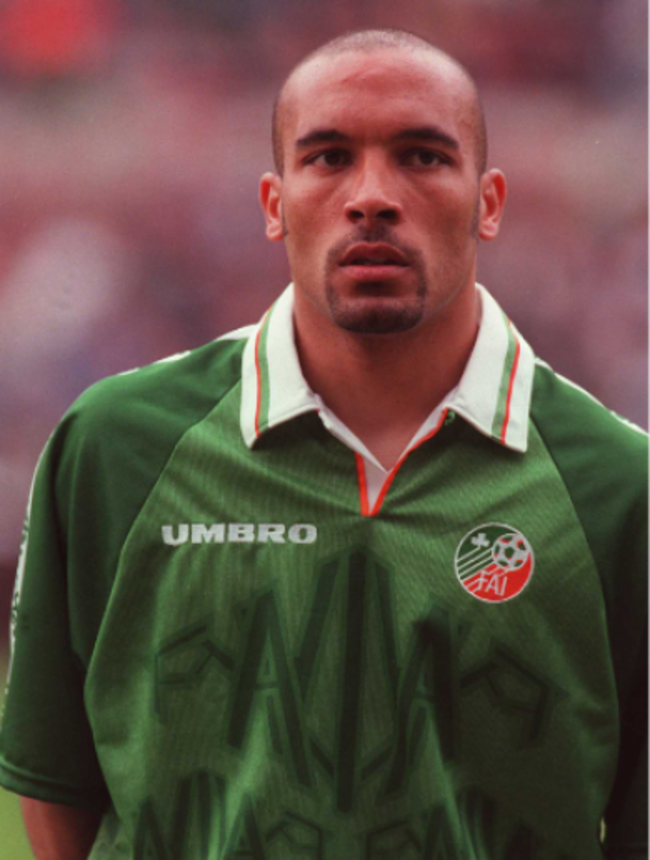

Despite being rejected as a youngster after going on trial with Tottenham and Man United, Fleming went on to make over 200 appearances — the majority in the Premier League — for Middlesbrough.

He also fulfilled a lifelong dream of representing Ireland, winning 10 caps. And it would have been more were it not a golden age for Irish full-backs, with Denis Irwin, Terry Phelan, Steve Staunton, Kenny Cunningham, Gary Kelly, Ian Harte, Stephen Carr and Jeff Kenna all vying for a spot in the team around the same time he was.

I would have been in probably 40 squads. I think Mick McCarthy even put it in his book at one stage: ‘Curtis never said no when I rang him.’ I wouldn’t get into his squad, there’d be a couple of pull-outs, he’d call me and I went. People said: ‘Are you not getting fed up going over [and not getting picked]?’ ‘No, why would I?’ I was looking at matches, I was going to Lansdowne Road. If I got offered a chance to be part of the Ireland squad, I’m going. And if I get my chance, I’ll give it my best.’

“And what I did like was that Mick was honest with me. He rang me a couple of times and he’d say: ‘I need you.’ And I’d say to my wife at the time, you know how we booked that weekend away for the international break? It’s not going to happen, I need to go. My bag was packed and off I went. So I was very proud of that. One cap would have been fantastic, 10 caps is absolutely brilliant.”

Moreover, in a pre-Covid world before wedding postponements were commonplace, Fleming missed his big day in order to represent Ireland.

“It was supposed to be Las Vegas and I ended up in Middlesbrough’s registry office.

“But again, my wife understood what it meant to me. I wasn’t going to give that chance up. Football, I felt that was my vocation and my dream. And I missed my first daughter’s birth because I was away.

“But I don’t want a badge or plaudits for stuff like that, you’ve got to be understanding where you’re coming from and why you’re in the game, what you want to achieve.”

I bring up a conversation with current Ireland women’s international Rianna Jarrett from a few years back. She spoke of drawing inspiration from watching Steven Reid as a youngster, a rare example of a black player lining out for Ireland. Was Fleming himself aware of being somewhat of a trailblazer and potentially inspiring future generations of black Irish men and women?

“I think so. I would look up to people [as well] — Chris Hughton, with his little afro. I think that even subconsciously, it’s brilliant for anybody. I was talking about coaches. If you want to become a black coach, you need someone to look up to. You need to know that someone has got there and it’s achievable. If there’s not, you’ve got to have so much drive to break that ceiling. I think Paul [McGrath] did that.

“It wasn’t just Chris Hughton, I wanted to be Liam Brady as well. But when you look and you know Paul was at St Pat’s, they’d be saying ‘you’re the next Paul’. No, there’s only one of him. He’s fantastic. But it was brilliant to know that someone who had played in Inchicore had gone all the way and you’re seeing him playing every week against quality people.

So there’s no doubt about it and what she said is bang on, because what it does is it just gives you a belief that you can get there. That you can do that. I’m not saying that it’s the be all and end all, but there’s no doubt that when you look, it’s every level of coaching. In the Football Association of England, there’s a big problem now, because you don’t see any black faces on the ladder on the way up at the top. So when you get to the top, I know you’re going to see a load of middle-aged white men in grey suits. You’re thinking: ‘Can I get there?’ But then again, Barack Obama probably thought that. And he made it. So we have to.

“And going back to big Paul, I made my debut against Czech Republic away and luckily Paul played in the game. It was an absolutely wonderful feeling, a player I’d looked up to.

“But when I was a kid, Chris was playing, and that was when you looked at it and thought: ‘I tell you what, this is achievable.’ I think you need that and hence, when we talk about black coaches, we cannot say to young black kids: ‘There’s no job out there.’

“I’ve coached in the Championship for most of my career at a good level at good clubs and I’m saying ‘yes, you can get there’. I want to go to the next level, I want to keep working, I want to show people that once you work hard and educate yourself, you’ve got an unbelievable chance, no matter what colour your skin is, or wherever you’re from.”

Racism, of course, continues to be a serious problem at every level of the sport — there have been countless incidents both in British and Irish football, as well as other European leagues, with the ‘White Lives Matter’ banner during the Burnley-Man City clash earlier this week the most notable recent example.

One vivid memory that Fleming has took place towards the end of his career during one of Shelbourne’s European games away to Steaua Bucharest. Both himself and Joey N’Do were subjected to boos and monkey noises by the home crowd. Former team-mate Stuey Byrne brought it up in a recent interview on Off the Ball and Fleming feels now that the reaction to such incidents back then should have been stronger.

“Stuey Byrne’s talking about it years after the fact and that shows you the impact it had on him. I think that was the biggest thing on the day for me. The support and the shock of all the guys to what was going on, what was happening in the game and the effect it had. The lads were as disgusted as us. It was not ‘Unlucky there Flem, that’s the way it goes.’ It was: ‘This is an absolute disgrace.’ And it’s still happening. It’s happening in a lot of countries around Europe every weekend. There’s no doubt about it Italy over the last few years, Russia, Croatia, unfurling banners with monkeys and bananas. The federations fining them €1,000.

“[The Bucharest incident] was mentioned on the day in the press, but there wasn’t a huge thing made about it. I think we could have been a lot stronger with it at that time. But I know now, if I’m coaching and anything like that happens, I will do something. I think Stuey Byrne would do something. I think Joey would. So it’s had an effect on us. It’s not a nice thing to have to deal with at all, I don’t care what age you are. I’ve had coins thrown at me, I’ve had monkey chants, I’ve had spitting. As a full-back going to get the ball, they’d be saying: ‘Go back to your own country, you black this, you black that.’

“Years ago, lads used to laugh it off a little bit and go: ‘Oh Flem, you’re in for a big one today.’ But now I think people are willing to stop games, they’re willing to say something, they’re willing to come out in the press. And I think with the press and social media as well now, you can very quickly identify and target the people who are perpetrating what I’d call a crime.

“And people keep saying, the biggest drivers of this are going to be the white public and population, because it’s the self-realisation that yeah, there have been a lot of unjust things, a lot of unjust feelings, a lot of unjust treatments, it hasn’t been equal for so many years, and now I’m realising that: ‘I didn’t know my friend was going through that.’ Or: ‘I didn’t know that this was happening in my workplace.’ And I think that’s going to be the biggest change.

I laugh, because my mother used to have a poster up in my house. She was very politically minded, she liked to go on marches, she was an actress. We’d go on marches with her, marches for anything. That’s the way she was and I think she’s brought it up in us and it’s in our blood to stand up for things that we believe in. It’s taken me a few years to realise as much. But you know the ‘no blacks, no Irish, no dogs’ sign? It was in a window in London. I think it was from 1960. Someone took a picture and it’s been going around for a lot of years. That wasn’t a million years ago. And that was in our house. There was a picture of that up on the wall, kind of saying to me: ‘That’s the way it was, son.’

“I think now: ‘Wow.’ Especially in Ireland, we’ve got to think: ‘How can we view racism?’ We populated most of the world, because we had to, due to the Great Famine, which was another political situation. At the time, potatoes were getting shipped back to England when there was none for the Irish. So how can the Irish say to people: ‘Get out of our country. What are you doing here?’ We have to look at ourselves first.”

The42 is on Instagram! Tap the button below on your phone to follow us!

Great read.

Fair play Curtis, always a great player, a great ambassador and very articulate.

Great article

Great read, didn’t realise how though his childhood was with his mother’s passing so young. Great determination to bring up his siblings and make an impact across the water.

An inspiring story, hopefully he gets a chance to coach in England in the future

Great read. He makes a good point about number of BAME managers versus number of BAME players… The former should be much higher.

Interesting guy,i hope his coaching career brings success.

I remember Curtis when he worked in a newsagents in Talbot street Dublin 1

Very nice guy

Great article and wishing Curtis the best of luck going forward

A great guy and a very enjoyable read. Best of luck Curtis!

Great read.

Great article. Let’s not shy away from our shortcomings as a country, no one should be victim to this sort of abuse. Welcome the diverse next generation of Ireland

A Boro legend

Curtis is a legend. Racism is a cancer destroying society.

Who gives a fuvk if you slate brown white back who cares your Irish x

@BriP75: stupid comment. Evidently some people cared enough about his skin colour to racially abuse the man growing up. That sort of ignorant attitude is the reason why racism still exists in society. Educate yourself…