FOR DECADES, THE notion of GAA literature was deeply unfashionable.

With occasional exceptions that meandered into exploratory areas such as ‘Over The Bar’ by Breandán Ó hEithir, the vast majority of examples were disappointing and drab paint by numbers autobiographies that would sprint with little subtlety from the first pair of boots presented to the subject, through their underage and senior career, inventory of injuries, the obligatory chapter taking a swipe at the GAA and then finishing with their all-time top fifteen players.

That theme never quite died off.

But ever since Liam Hayes re-imagined what a GAA autobiography might be with his ‘Out Of Our Skins’, the artform took a welcome leap into innovative territory.

Various concept books have come and gone and left their mark. The winners no longer write the history, with the likes of Keith Duggan’s ‘House Of Pain’, a painstaking pick over the bones of Mayo football’s failure since 1951.

Historical accounts have been superbly executed, such as Michael Foley’s ‘Kings of September,’ and Paul Fitzpatrick’s ‘Fairytale In New York.’

Meanwhile, the very idea of who might write an autobiography has been democratised.

Thank God for that too. This year, we had Eimear Ryan’s stupendous and illuminating ‘The Grass Ceiling’ on what it is to be a girl growing up into a woman within her own high-achieving GAA family, and the general GAA family and different clubs.

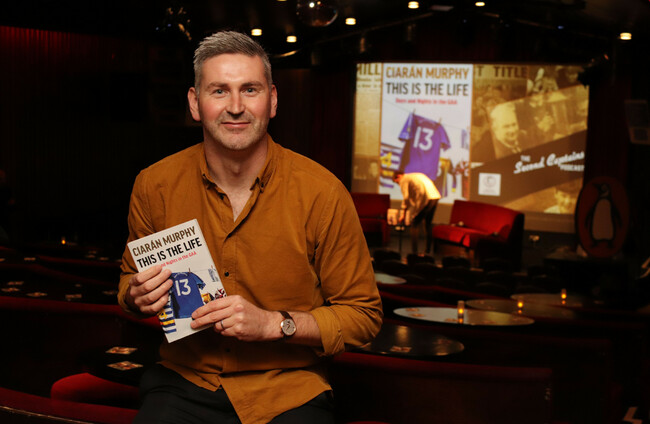

This is where we land on with Ciaran Murphy’s ‘This Is The Life.’

The one-time ‘Off The Ball’ staffer with Newstalk, later to branch out with his buddies to form the ‘Second Captains’ crew, Murphy was a handier footballer than he gives himself credit for.

A quick run through his credentials. He played for the Galway U21s, made it to a Connacht final. He was first sub off the bench, replacing the injured Matthew Clancy, while Michael Meehan and Nicky Joyce were also in that attacking division. On the other side was Andy Moran, Conor Mortimer and Alan Dillon.

He reached the 2007 county final with Milltown, losing to a Pádraic Joyce-led Killererin. None of this is to be sniffed at, but the vast majority of his career wasn’t a matter of national importance.

Which is ideal. Because 99% of players never get to experience that stuff either. Instead, he talks of growing up with a remarkable and loving father, Tony, who was recruitment officer, coach, registrar and manager of generations of lads to pass through Milltown GAA in Galway.

He talks of going to St Jarlath’s Tuam and, instead of a predictable romp through winning Hogan Cups, he didn’t actually make the team. He never let it sour his love for football.

He writes of his teenage fanboying of Ja Fallon, which was granted another dimension when he worked part-time for Fallon’s brothers in a clothes shop in Tuam and had regular access to his hero, hanging around him and chuckling along like someone in Muhammad Ali’s entourage.

There’s fantastic, moving segments in which he outlines the footballing culture of Tuam and surrounding areas, how Pádraic Joyce might cut a fella to the quick on the bank with crowds gathered round to hear the quips during another hectic round of club championship. The sheer gentlemanliness of Michael Donnellan as he helped carry him off the pitch after an injury against Dunmore.

You get to see the dilemma some are left with when they want to live somewhere else but there’s still the well sharpened sense of emotional blackmail that pulls them back to the old sod, weekend after weekend, in the hunt for the championship.

And the agonising over whether lads in a clubs’ second or third string team will go and spend the entire weekend at Electric Picnic, or else curtail the madness for a few hours and come play a game of Gaelic football.

It’s a book for the everyman, not one that is blinded by the woefully inadequate and somewhat small-minded notion of ‘One Life One Club.’

“So much of it in sports writing now is couched in this ‘high-performance’ language, which drives me demented,” Murphy opens the chat.

“This idea that if you are not doing it in such a way – that you have to sacrifice everything else to become the best – then you are doing it wrong?

“Well, it’s the most perverse and perverted way of understanding what sport is supposed to be about. Whatever about being in an academy at 17 in Man City and you are trying to get your grandkids rich… If you are playing Gaelic football or hurling, it is about enjoyment.”

He had a spin on the county Under-21 team. He played a decade of senior club football in Galway and ghosted in to the UCD Sigerson panel through Bryan Cullen’s coaxing. But he doesn’t feel like he short-changed himself either.

Through the Sigerson connection, he transferred to Dublin club St Vincent’s. But it wasn’t the right fit. Years later, he joined up with Templeogue Synge Street and it’s been incredibly enriching.

“I know that I am not the most reliable narrator in this. There are certain golden rules in the GAA on all of this; the ‘One Life, One Club’ thing,” he states.

“This idea that there has to be this great suffering to get there in the end. I disagree fundamentally with both of them.

“The fact that I transferred from my home club, the (book) launch brought it all back home to me; what an unbelievable privilege it is to be a member of two clubs, two welcoming communities that wrap their arms around you. It’s a real eye-opener for me in that respect.

“The idea that you should only experience one unit of the GAA – for many people that’s the reality, they get a chance to stay at home and work at home and that’s beautiful as well. But I don’t think we should be tyrannically policing the idea of ‘One Life One Club.’”

In the book, you get the sense throughout the 2022 season that this is it, for him. His body is giving him bother. His back is a constant reminder of his age and he’s no longer guaranteed a starting spot.

Until he tells you that a spot of Pilates sorted his back out over the winter and he’s flying it.

Last weekend they lost a county quarter-final to St Jude’s with the third team. He played in the league with the intermediate team this year and in one five day spell, fitted in three games, one of which was doing goal for the club senior team. And he played for the Dublin Masters team this year too.

“I didn’t do that when I was 19,” he laughs.

“At 19, you are afraid of burnout. At 41, you are like Robert Shaw heading home at the end of ‘Jaws.’ You are sinking anyway, so you might as well burn the engine out.

“As for next year, that’s for next year. I could see myself not putting the boots on in January and February. I am looking at the mouldies and thinking I might throw away the studded boots. Just be a ‘mouldies footballer.’”

There’s a bit of a tradition in Templeogue Synge Street of playing as long as you can. Murphy cites Joe O’Reilly – husband of Mary Black, father of Danny, the lead singer of The Coronas, and how he played until he was 58 and, even at that, should have gone on for another while longer.

41 now, he doesn’t take it for granted.

“Every time you play now, you feel so lucky to do it. It’s the sort of thing people say without thinking too much about it. But I am genuinely feeling that. Every time I train on a beautiful evening, I think that I am long enough not doing this. It’s just great,” he adds.

“That’s the motivation, walking in with one of the lads who is half your age, spent seven or eight years of their life in the gym already. And you know that some day, I am going to get blown out of the way. Some lad is going to go through me for a shortcut, and I will get injured, it will be a humiliation, and that will be it.

“You know that’s the case, but you are not going to let that guy do it to you. Your competitive fire is still there.

“So I go down there and I enjoy training so much. I squeeze the marrow from the bone of training. And then when the game comes round, maybe two hours or three hours beforehand, you want it to come right then.

“When the ball comes in your direction that’s the whole thing. What are you going to do with it? There’s still no feeling better than that.

“I know if I go coaching and into club committees and that, you will get a beautiful enriching, continuing relationship with the GAA. But there’s still nothing like having the ball and the whole 30 players is revolving around you for that moment. I’ll still be chasing that in two or three years from now.”

He’s not a cheerleader for every element of the GAA. But even in his criticisms of the sporting body, it is clear that it comes from a place where Murphy is absolutely, head over heels obsessively in love with the GAA, the culture around it and what it has given him and his family.

That fondness is captured here brilliantly.

As an Irish fan I’m thinking it’s a case of what if. He had more to deliver for Ireland. Kinda ashamed our dull playing system shut him out and deprived him of more caps his career deserved, never mind bickerings about his fitness. We are not exactly gifted in the football brain department! Hope we have future Andy Reids in the pipeline!

He was overweight his whole career.. he has some of the blame. Lovely player though.

I’m sorry but if you are a professional athlete and you cannot maintain a decent level of fitness, you have no place near any team.

For too long Irish managers were bullied into selecting this guy by the press. Wes Hoolihan was similarly talented but wes, who unlike Reid only made it to a high level late in his career, applied himself and now has an international career to be proud of. Similarly the most talented Irish player of that age, Damien Duff, was also one of the hardest working and had a great career as a result.

Fair enough boys. His end of year school report would look like this, “Talented but needs to work harder” – story of his career. However the systems his teams adopted didn’t do him many favours.

Wand of a left foot

All fair comments here. He wasn’t able to have a consistent run the in premier league which had it’s fair share of limited players and journeymen. Which for a player of his talent a bit of a travesty.