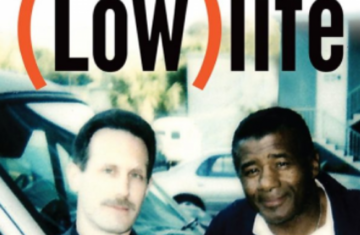

THE FOLLOWING PASSAGE is an extract from (Low)life: A Memoir of Jazz, Fight-fixing, and the Mob by Charles Farrell.

My Heavyweight Gets a Title Eliminator and I am Stuck in a Crowded Van All Afternoon with Naseem Hamed: The King’s Hall, Belfast.

Braverman asked, “Can your fat white kid fight at all?”

“No.”

“I mean at all.”

“No.”

There was a short pause on the line.

“Well, that’s OK. Don will give him the shot anyway. What’s his record? We just need someone with a good record. It’s short notice.”

“He’s 11-2-1.”

“That’s fine. Besides, this South African kid can’t fight much either.”

“Is it Botha?”

“Yeah, Botha.”

“No way my kid beats him, but he’ll probably go the distance.”

“If he goes the distance, we’ve got things for him to do. If he goes rounds, we’ve got things for him to do.”

“With Botha? He’ll go rounds. That’s the one thing I’ll guarantee you.”

“Good. I’ll have Connie send out a contract. And I’ll send you a check on the side. We can chop that one up however you think is right.”

I had a good working relationship with Braverman. He would call to ask my advice about fighters who were under consideration by Don King Productions. In exchange, he would get my fighters spots on King cards.

I’d had the good sense to buy Foster a just-in-case win a month after his loss to Melvin Foster. No Floyd Patterson involvement, no publicity, just a no-frills trip to Raleigh with three other fighters to put wins on their records.

Foster’s opponent, James Cowan, was an encouragingly too-muscular former football player in the Canadian League. He’d never fought before, and arrived at the Ritz with Bermuda shorts and low-topped sneakers as his boxing gear. Before the fight he called me into his dressing room with a last-minute plea that Foster not hit him in the face since he was wearing hard contact lenses that might shatter.

I assured him there’d be no head shots if he promised to fall down at my signal. The fight looked like exactly the sham it was, with a visibly petrified Cowan cowering and blinking wildly through his contacts.

The crowd starting laughing the moment they got a load of Cowan in his sneakers and shorts, and were booing before the first minute had passed. In the corner I had to instruct Foster—who, as he’d been told, was not throwing any head shots — to shut down the sideshow.

A few seconds into the second round, as Cowan pitiably beseeched the referee with an outstretched arm to let him be excused, the fight was stopped.

Based on this KO victory, we found ourselves in Belfast one month later, with Foster fighting Frans Botha of South Africa in a title eliminator for the right to take on Michael Moorer for his version of the crown.

I understood that Foster was a sacrificial lamb. He understood it too. But I drilled into him the idea that Frans Botha was no killer.

It was freezing cold in Belfast that March. The city was toxic, embroiled in the height of the Troubles, with checkpoints in every shopping centre where armed policemen went through the handbags of old women doing their marketing and bookbags of children on their way home from school.

Armoured tanks did slow routine sweeps of the centre of town under heavy verbal bombardment from the overflow of drunken traffic staggering from the many bars. Belfast was on high-alert; everyone held a grudge. It was an angry and aggrieved town with two or three partially bombed-out buildings on each block.

People drinking in the bars below us were belligerent, assuming that everyone staying at the hotel was a rich foreigner, and mostly being right. Fists were shaken at us; oaths mouthed. We were somehow seen as being collusive with the armed patrols circling the area.

One late night, a young woman stumbled from the bar directly across from us and caught me looking at her. She immediately executed an about-face, dropped her drawers and shook her ass at me. It was exactly the kind of thing that Betty would have done as a young woman: “Póg mo thóin.”

I’d be booked into the hotel room next to commentator Al Albert’s, forced to overhear his half of garbled conversations, spoken in an affected British accent, with room service: “I’d like a spot of tea brought up. Yes, yes, a spot of tea. No, tea. Te-ay. A spot of tay.”

I wondered what besides tea might have been added to those pots after catering got a load of that British accent.

I was hanging out with Tony Petronelli in his room one night, going over Foster’s fight strategy. The phone rang and I picked up. It was Pat Petronelli. He recognized my voice, but was already committed to what he’d expected to say.

“Chaales, it’s . . . Dad!”

Because many of the fight people were decamped in the same hotel, it was inevitable that we’d run into each other in its restaurant, a glass-enclosed space that overlooked the town square.

Botha’s guys hung out there, and I found myself growing to like them. The two members of his team were West Coast veteran trainer Jackie McCoy and former WBA heavyweight champion Gerry Coetzee. They were keeping company with ace cutman Chuck Bodak, the goateed, shaven-headed octogenarian eccentric who made his own silver and turquoise jewellery and came to the ring with headbands festooned with slogans about whoever’s corner he was working.

King hadn’t set aside additional money for a third cornerman, and I was unwilling to spend any more of my own on Martin Foster. Tony Petronelli was the only one I’d brought to work his corner. Neither of us was really a cut man, so Bodak offered his services.

Ordinarily, I’d have never considered letting someone who might be said to be working for “the other side” near my fighter’s corner, but I knew a lot about Jackie McCoy, who was seen by everyone in boxing as the most stand-up of people. Although he knew every trick in the book, it would have been beneath him to set me up. It was also evident that McCoy, Coetzee, and Bodak saw this fight as a free win for Frans Botha. We were going to need a cut man for Martin Foster. Chuck Bodak, whose reputation had been cemented through his televised work with Oscar De La Hoya, was one of the best.

The day of the final press conference and weigh-in was gray and cold with a steady mist that managed to find its way through outer layers of clothing. Everybody was in a grim mood. A van came to the hotel to bring some of the fighters to the proceedings.

Martin Foster, Tony Petronelli, and I stepped from the chill into an overheated van already semi-crowded with fighters, including one tiny creature who, with his enormous ears and pointy little teeth, appeared to be a vampire bat.

The tiny creature was talking. Although I recognized Prince Naseem Hamed immediately, my subconscious frantically tried everything at its disposal to disavow acknowledging his presence.

I knew he wasn’t going to stop talking. And he didn’t. Prince Naseem Hamed was a major fistic star in the UK, idolised as much for his flair and style as for his boxing unorthodoxy and big punch. But it’s safe to say that I’ve seldom met a less charismatic or more tedious human being. He was a runt, a pipsqueak. He was a fucking popinjay. As tiny as he was, his energy took up every vestige of air in the crowded van. It was like being trapped in a wet chimney flue wearing a soggy woolen overcoat.

Hamed bragged and bragged, animatedly throwing demonstration punches that caused fighters who had actual fights scheduled on the card to duck.

“Nobody can do the shit I do,” he opined. “Nobody has my kinda flair. And nobody gets up when I hit ’em.”

There was some irony in all this. I was managing Freddie Norwood, who would have destroyed him had they fought. It would only have agitated the insecure Prince if I’d told him that, and the unpleasant atmosphere inside the van would have multiplied tenfold. I kept my mouth shut.

I got a close look at Frans Botha at the weigh-in. At 231¼ pounds, with short arms, “The White Buffalo” was a roly-poly little fatty with a crooked smirk and a whitish-blond patch of hair perched like an ill-fitting rug.

Botha’s record of 29-0 was more impressive than he was. His best opponent to date had been the tricky Mike “The Bounty” Hunter. Hunter, despite being a light puncher, had managed to drop The White Buffalo on his way to losing a split decision that he’d deserved to win.

Despite his dubious credentials, I knew that Botha was better than my fighter and that business reasons favoured him getting the nod were Foster to put in the performance of a lifetime.

I was past the point with Foster where I was willing to boost his naturally inflated, but now experientially deflated, ego. I no longer gave a fuck about him. I was there to collect a payday and to see if he could lose skillfully enough to allow for a few future paydays. He owed me money, and I was in Belfast to get a little of it back.

At a local gym, Tony and I had tried to give Foster a fight plan geared to provide maximum short-term utility: unless an extraordinary opportunity presents itself, lose the fight, but do it in a way that allows the door to stay open for purses of similar sizes.

As Tony worked the pads, I told Martin, “Use your legs and your jab. Botha’s carrying too much weight, so make him chase you. You’re in better shape than he is. Move all 10 rounds. Once he gets tired, if you can dig to the body without putting yourself at risk, do it. But I want that jab in his face all night, and I don’t want you standing still. He can’t punch, so he’s not going to knock you out. Just go the distance and King will bring you back. You got it?”

“Yes, sir.”

Even though Martin Foster’s jab was nowhere close to what Merle Foster thought it was, he had a decent jab. It was the only punch he threw correctly. And, enormous waistline notwithstanding, he could move a little bit.

So, Objective Number One was to not get knocked out. Objective Number Two was to try to win the fight if it didn’t interfere with Objective Number One.

Showtime PPV sends someone with a handheld camera bursting into your dressing room after you’ve had the fighter gloved up for an hour or more. The camera is on a dolly, and the crew thrust it within a foot or so of your face, then gesture for you to follow them as they back up into the arena. They move slowly, but purposefully. The dressing rooms in King’s Hall are below arena level, so you’re moving on a slight incline from a relatively darkened area into one that is suddenly brightly lit once you’ve crossed the threshold into the Hall itself.

Unlike in the US, UK fans go to the fights to see the fights, not to be seen at them. They come early and stay until the end. The card’s main event was a rematch between WBO super-middleweight champion Chris Eubank and Belfast’s own Ray Close one year after their first fight had ended in a draw. The rematch was among the most significant fights in the city’s history, guaranteeing a full and wildly partisan house.

The enthusiasm trickled down to the card’s preliminaries. When the crowd caught sight of Martin Foster, with Tony Petronelli, Chuck Bodak, and me accompanying him, the din they created was enormous, going straight up to what looked like a pressed-tin ceiling, amplifying the volume and reverberating through The King’s Hall.

We entered the ring, where Frans Botha was already waiting in the opposite corner. The lopsided sneer was still in place, but he suddenly didn’t look so comical. Or so fat. The motherfucker somehow looked big. The ring, on the other hand, looked very small, as it always does when heavyweights are fighting.

We moved to the centre to get the referee’s instructions. Not for the first time, I felt grateful knowing that I’d be ducking back outside the ropes in a few seconds. There was just enough time to remind Martin Foster, “Remember, use your jab and your legs. Jab and move.”

At the bell, Foster came out as instructed; Botha, the smile never leaving his lips, circled in nearly slow motion. He began waving his right glove in an exaggerated bolo—a kind of mocking gesture. Then he threw a wild uppercut from too far back, a sucker punch that everyone in King’s Hall except Martin Foster saw coming. The shot evaporated Foster’s nose, sending a scenic waterfall of blood down his chest and stomach. Martin started to drop, but stayed upright by holding onto the ropes.

Botha, still doing everything in slow motion, laughed. He repeated the absurd glove-waving pantomime, threw another uppercut that everyone in King’s Hall except Martin Foster again saw, landed it on what would have been his nose if he’d still had one, and the referee stepped in to stop the fight as Foster sank to the canvas. One minute had elapsed from the opening bell.

Foster almost made it down the ring steps before his legs went out from under him. Luckily, Tony, Chuck, and I caught the fighter and managed to hold him up, then more or less carried him back to the dressing room.

We got him seated, and Bodak put the spit bucket on the floor in front of him.

“Son, your nose is broken. I want you to breathe in hard, then spit into the bucket. Just keep doing it.”

“My nose ain’t broke.”

“Alright. But just do it.”

An appalling amount of blood was spat into the bucket. It didn’t stop. Martin would breathe in as hard as he could through his nose, spit a mouthful of thick blood into the bucket, repeat it again and again. His eyes were already closing up. It was terrible.

The doctor came in, explained to Foster that, yes, he did have a broken nose, and a badly broken one at that.

I saw Martin Foster at the airport the next day. His whole face was swollen shut; his eyes, blackened as a result of his broken nose, were barely slits. It was the last time I ever saw him and the last time we ever spoke.

I explained that I was taking all of the money from the fight. He owed me a lot more than that. I also told him that if he promised never to fight again, I wouldn’t come after him for the rest. I stressed how important it was that he quit boxing immediately—that his health was at risk otherwise. He was no fighter.

Martin Foster promised me that the Botha fight would be his last. We shook hands, then took separate planes back to different parts of the US. I was glad to be rid of him. He’d only needed to do one simple thing, but he couldn’t manage even that.

(Low)life: A Memoir of Jazz, Fight-fixing, and the Mob by Charles Farrell is published by Hamilcar Publications. More info here.

Started 2 months ago myself. Training a few times a week now and feeling great. Found an ab last week…least I hope it’s an ab!

I think the main problem with running as an activity is that ultimately it gets boring for a lot of people, so you end up dropping out and then find it hard to get back to it. I find I get the most out of running when I tie it into some leisure activity like cycling , or hiking so it becomes a means to an end. That being said it is a good all year round activity and it can be as nice going for a run in Jan as in July. And do vary where you run even if it means jumping in a car or running with a friend on the other side of the city. Another one might be to find some forest/hill routes if you are drivable distance from hills/mountains

Podcasts are a good way to beat the Borden ..

@silverharp would be kind of hard for a total amateur to go shell out big money on a proper racing bike with all the gear, especially if they’ve just worked over 40 hours in the week for their 50 euro job bridge allowance… I can see why they would opt for just a pair of runners instead!

@Ashley Rowland lol, I thought the Tory approach was to get on your bike ;-) and where did I mention expensive racing bikes and gear? any sort of bike will get you to Enniskerry or the Sally gap. Lack of imagination will be your biggest problem and keep an eye out for Lidl specials when it comes to gear.

I love to run. It’s relaxing and give you a break from the real world!

Those 5k and 10k races around the country are very good motivation. The Dundalk 10k race got me motivated anyway 3 years ago and in 2012 I managed to run sub-40mins, which I was seriously delighted with.

Unfortunately there was a poor turn out this year for that race, lets hope it picks up again in 2014 :)

If you want motivation to run read “Born to Run” by Christopher McDougal…

Outdoor exercise has really taken off in the last number of years. I think the biggest danger to quitting is when you stop improving your times. However there are a huge amount of events out there now to encourage a person to keep at it and get enjoyment out of it There are 5k, 10k, half marathon, marathon, triathlons and mixed events taking place throughout the country. There are also many walking and hiking trails and paths/greenways for running or cycling. So there are plenty of new places to see and explore. It is definitely much better than the gym.

Compared to someone Living in London say, Dubliners in particular are spoilt for choice. Poolbeg lighthouse, Bull island or head into the Dublin/Wicklow hills, Crone wood etc. as a goal or just to make a day of it.

Its getting from the couch to the 5k finish line

Rest I’d say mate. No expert but I found that a 5 min walk is not sufficient warm up. Lots of stretching before hand.

On week 2 and think ive pulled my calf mussel very sore. Any advice should I rest or go on as normal

Use a foam roller after a run. you can find very good videos on youtube showing you how to use it.