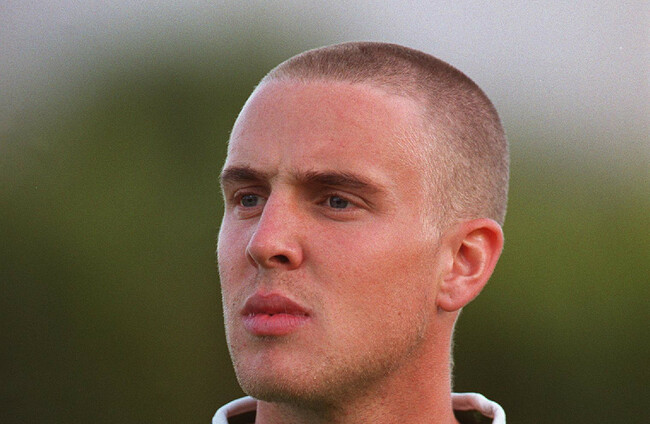

BARRY QUINN vividly recalls the night before he left for England having just turned 16.

He had secured a move to Coventry City, a Premier League team at the time, despite putting in what he considered a sub-par performance for Ireland U15s against the North.

“When it happened, I was buzzing,” he tells The 42. “But then the reality kicked in. I remember I was with all my pals. There was a playground near where we lived.

“It was the last night before I was going. But I couldn’t say goodbye because I thought I’d break down, so I just legged it. When they weren’t noticing [me], I just legged it. Because I said ‘I can’t, I’ll end up getting upset and that,’ you know what I mean?

“They did knock around afterwards: ‘You never said goodbye.’ I couldn’t face it.”

Those closest to the Manortown United graduate were equally uneasy about the looming move.

“[My parents] were obviously happy for me but they were gutted [deep down]. My ma only told me after, years and years later, that she used to get really upset that I’d left. They didn’t show it in front of me.

“They were happy for me because it’s what I wanted to do. And they were buzzing for me. But at the same time, my mam used to say ‘I didn’t want to say it at the time, but I was really upset.’”

Quinn gradually grew accustomed to life across the water and the club looked after him well, though this unfamiliar experience was not without its challenges.

“Coventry was one of the first places where the youth team players lived at the training ground,” he recalls.

“There was me and another Irish lad, John Andrews. All the other English lads went home at the weekend to see their families. We were stuck there by ourselves, so that’s when it got a bit lonely.”

The boy ultimately grew into a man, however. A seminal moment in Quinn’s footballing education occurred in the summer of 1998.

Not only was the Dubliner part of the Ireland U18 side that earned a historic victory over Germany to win the European Championships, but he also captained the side to glory and scored in the 3-0 victory over hosts Cyprus that secured their place in the final.

“It was a golden moment for Irish football, wasn’t it? I remember the year before I was watching the U20s,” he says.

“Damien Duff was probably the best player in our age group when I was in schoolboy football. I played in the U15s, U16s with him leading up to that. So I knew Duffer. I remember he obviously got picked to play for the 20s.

“He just shone then. He started to grow. And the lads were brilliant, they got to the semi-finals [at the 1997 World Youth Championships]. They were unlucky, they got beaten by Argentina, who eventually won it.

“Great memories, great set of lads, brilliant team, great players that went on and had great careers. I was just blessed and fortunate to be in that [U18s] team and captain it as well. Some good memories and to be fair, it wasn’t just a one-off thing, we played in the March before that as well and won a tournament in Portugal and we played some good teams.”

Less than two months after being part of this remarkable Irish footballing success story, the 19-year-old Quinn was handed a Premier League debut.

The circumstances could hardly have been tougher. He was picked to start against Manchester United at Old Trafford. The Red Devils would claim a historic treble at the end of that season.

Quinn featured in a Gordon Strachan-managed Coventry team alongside the likes of Paul Telfer, George Boateng, Gary Breen and Dion Dublin.

He was up against one of the greatest midfield quartets in the history of English football — Paul Scholes, Roy Keane, David Beckham and Ryan Giggs.

“I didn’t officially find out [I was playing] on the Friday but you kind of know when you do your team shape in training.

“Sometimes the manager would throw a little wobbler in now and again to test something — take some players out to see how they react or put players in.

“It was surreal, but you’ve got to focus on what you’re doing. I can’t remember any of the game at all. I was so focused on what was going on, it was hard to take it in. I remember going out for the warm-up, coming back in.

“Gordon said to me: ‘You’re making your debut against your country’s captain, if I see you standing off him you’re coming off straight away.’ So I was a bag of nerves.

“But I did okay. The manager said to me ‘well done’ after the game and that I did well. We ended up getting beaten 2-0, but we did okay to be fair.”

At that point, some would have viewed Quinn as a potential eventual successor to Keane in the Irish midfield, and the Corkonian had brief words of encouragement for his younger counterpart after the game.

“He just said ‘well done,’ came up and shook my hand,” Quinn recalls.

“But I knew straight away, if you get something out of him, you know it’s probably a compliment.”

Quinn would go on to gradually establish himself as a first-team regular at Coventry.

Things were looking up and in April 2000, he was rewarded for his fine form with an Ireland debut against Greece, becoming one of six players out of 18 from the famous U18s squad that would ultimately graduate to senior international level.

He could hardly have dreamed of a better start to his career, nor could Quinn have envisaged the misfortune that was to come.

***

As with many footballers, Quinn’s reflections on his career are bittersweet.

Feelings of ecstasy and dismay never seemed far apart, perhaps epitomised by the night he made his Ireland bow at Lansdowne Road amid a 1-0 loss to Greece.

The joy of playing in the stadium he had frequented as a fan in his younger days was offset by a serious injury that led to his premature withdrawal from the action in the 34th minute.

Quinn had gone close to scoring before a challenge from Ilias Poursanidis ended his game “on a sour note,” as The Guardian’s report from the time put it.

“I tore my ankle when he tackled me,” he says. “I went down and I could feel the crunch.

“I played for probably two to three minutes after. And then obviously, Mick [McCarthy] pulled me off.

“I didn’t see the [rest of the] game. I didn’t know what happened. I went straight to the hospital.

“It wasn’t broken but I ruptured the ligaments.

“I then didn’t get back to the hotel until later that evening well after the game.”

Quinn still recovered in time to feature in an end-of-season US Tour. He was called up after Roy Keane and a couple of the more experienced squad members withdrew, winning three more caps against Mexico, USA and South Africa.

Buoyed by the emergence of several talented players from those fabled Brian Kerr-managed youth teams including Duff, Robbie Keane and Richard Dunne, Ireland went from strength to strength thereafter.

Yet by the time they were qualifying for the 2002 World Cup amid the deeply hostile environment of the Azadi Stadium in Iran, Quinn was out of the picture.

He was part of a Coventry side that suffered a demoralising relegation from the Premier League in 2001 — the Sky Blues have not been back in the top flight since.

The last of his 83 Coventry appearances came in February 2003.

After a debilitating injury, he spent time on loan at Rushden & Diamonds and Oxford United, before signing permanently with the latter on a free transfer in the summer of 2004, around the time of his 25th birthday.

Within the space of three years, the Dubliner had gone from playing in the Premier League to the fourth tier of the English footballing pyramid, departing his boyhood club nearly eight years after signing as a trainee.

“I was playing with Coventry and the season would have been 2002-03. I came back from pre-season and I had a problem with my knee.

“I got an x-ray and a bit of my patella had broken. I had to get it taken out so I had to get an operation on my knee. I missed the start of the [next] season, I was out until about November, or December. And Gary McAllister, who I had played with, had come in as manager. He’d left to go to Liverpool and then he came back as player-manager.

“I hadn’t played so I went out then to get some games. I went to Rushden and Diamonds [on loan]. I had a month there, I came back. My contract was up the following year and it wasn’t getting renewed.

“So I ended up going to Oxford, who were League Two at the time.

“I was gutted leaving Coventry at the time. I would have liked to have another chance and give it another go and get myself properly fit and try to prove myself, but the manager had his own thoughts and ideas, so that’s the way football is I suppose.”

Quinn is reluctant to use the long-term injury as an excuse for his career at Coventry not working out ultimately.

“There are different things I could have done that might have changed that myself.

“I wish I had the knowledge I have now, 20 years ago, even now without playing the game, the knowledge you have as you grow up about how to look after yourself and how you train.

“But I suppose so many people could say the same thing, couldn’t they?”

Coming from an era in which training methods and sports science were far less sophisticated compared to today, he elaborates: “A certain player might need to work on their stamina or a certain player might need to work on their agility. So it’s more tailored toward the individual [now], they’d have more in-depth analysis from different people.

“Before that, it was just like: ‘Right, this is it. You do that. You train. And you run.’ But now, they’re getting the best out of people [in different ways].”

Quinn’s time at Oxford was similarly mixed. He made almost 200 appearances and was installed as club captain over the course of a five-year period. However, there were more failures than successes during that time, notably relegation to non-league level and playoff heartache.

A few days short of his 30th birthday, Quinn’s career as a professional footballer was effectively over after Oxford announced he had been released.

“I remember it was [future Sheffield United and Middlesbrough boss] Chris Wilder who came in. The same thing happened. I got an injury. I did my ankle [and was ultimately left go].”

Quinn spent another few years playing part-time football with Brackley Town before hanging up his boots for good, as his luckless streak with injuries continued.

“We played a pre-season game against Nuneaton Borough, and I went up for a header.

The lad pushed me, and I fell on and broke my ankle. I came back, tried to train and it wasn’t right. So I ended up having to have another operation. They put a plate on my ankle because it wasn’t set right.

“I literally didn’t play half of that season. I came back. I was struggling with it anyway, taking painkillers, co-codamol, in training sessions just so I wouldn’t get the pain during it and after, I was aching.

“I hadn’t played and the manager at the time said: ‘Will you play a couple of little games just to try to get fit down where I live rather than in Brackley.’

“I wanted to just play a game. So I went down, played two games [in Daventry] and I just went: ‘I can’t do this.’

“Without being disrespectful, when I started playing the game, I can’t remember who we were playing and I was just like: ‘Nah, I think my time is up.’”

After retiring from playing, Quinn did his coaching badges but opportunities were subsequently limited and he couldn’t afford to stay in the sport.

“It’s hard. I hadn’t done anything in my life other than play football,” he explains. “There were a couple of things I had to deal with financially at the time.

“I was friends with Gavin Strachan, so I did a bit of coaching at his coaching school. But because it wasn’t helping me enough financially in terms of what it was, I had to go and get some jobs [outside of football], work and try to get some money in.

“I’d done alright in the game but hadn’t been someone that earned that much money where I could just sit back.”

***

Now 44, Quinn still lives in Coventry, 28 years after originally making that daunting trip across the water.

“You don’t realise it when you leave, you think ‘I’m only going here for a few years,’ you don’t think you’re going forever,” he says.

“I’m settled here now, I’m probably not moving, my kids were born and go to school here. My wife is from here.”

Quinn still attends Coventry games on occasion and sporadically links up with old teammates to play charity matches.

He works a delivery job that is flexible enough to enable him to devote plenty of hours to watching his 11-year-old son follow in his footsteps.

“Sometimes, I get more nervous watching him than I did when I was playing myself. You get that little bit of adrenaline back. I love watching him playing and doing well, and then you get upset for them when they’re upset. So you have those emotions that you had when you played a little bit, it’s great.”

Not everything worked out according to plan, so the ex-Ireland international’s feelings about his career are understandably complicated. However, very few people can boast of captaining their country to the European Championships or enjoying a debut at Old Trafford against a now-legendary team — memories no one can take away, regardless of the less spectacular second act of Quinn’s story.

“Obviously, you always think ‘I could have done this, I could have done that.’

“You always think you could have done better. People say: ‘Oh, you did this and that,’ but it could have worked out a lot better as well. I stopped playing properly a good few years now. You can get over that but it does hurt you when you finish playing and think: ‘I wish I had done that.’ ‘If I could turn back the clock now.’

“But then I look at it on the other hand and say I’m lucky to have done what I’ve done at certain times. And I look back with a bit of pride as well.

“I wouldn’t want to start making excuses. We all have to deal with adversity playing football.

“There are always setbacks, but I did have a few badly-timed injuries as well.

“But I’m not going to turn around and say ‘that’s the reason why’.

“It was partly myself. I could have been better at times.”

Roddy Collins would win the World Cup with that squad…..

All he’d have to do is add Roddy jr and it would be the dream team

Scary to think 7 of these wont be going.

God, just reading this list is scary. What a team.

Mata yes, but Torres?

Controversial but Torres has yet to let Spain down. Two man of the match performances in European Championship finals and a world cup to boot.

Long time ago

He wasnt exactly in rude form ahead of 2012 either.

In fact when Germany went to South Africa they brought Klose and Podolski with them and they had 3 league goals between them.

Germany went on to be the highest scoring team in the tournament and Klose missed out on breaking an all time record over a cold.

Some National teams have their men and they trust them regardless of form.

Pssh. That squads no match for the likes of McShane or McGeady.

Paul Green.

As a Chelsea fan I’m delighted for mata, great player and only for the move he would not have been in

As a hated Chelsea fan I hope Fernando has a great World Cup, god knows he’s been putting in the effort.

Yes, I also put in a good effort at the weekly 5-a-side, can I play for Spain as well?

It’s a pity but it might be something to do with you not being selected – have a go anyway.

How did torres got in is beyond me

Is he relayed to the wine makers, they are like royalty in Spain , it the only way I can figure him being brought .

He ended up top scorer at the confed cup last year. Its not like Villa or Llorente are that great either.

Nice squad

Spare a thought for Diego Lopez, playing 18 months straight in the league for Real Madrid and not making the plane.

These lads even have class goalkeepers!

There’s gonna be a lot of pressure on Brazil particularly if they have a bad start, Spain will be confident

Brazil, Argentina & Uruguay will take beating.

Torres the Paul Green of the Squad

There are no weak links in that squad

I think they will walk it ….can’t see anyone stopping them

Winning 4 major tournaments in a row would make them the best ever in my opinion.Can’t see it happening though.

I’d predict the 7 cut to be Juanfran, Moreno, Iturraspe, Mata, Cazorla, Llorente, Torres

Not sure it matas too much for spain to leave out isco