MIKE FORD HAS an interesting take on his position as head coach of Bath.

The Oldham native is a former defence coach with Ireland, Saracens, the Lions and England, all of whom performed impressively in this area under Ford.

That experience has stood him in good stead for his current job as head coach of Bath, given that he now has control over his team’s attack too.

“One of the nice things about my current role is that it gives me the chance to turn all the experience on its head: to take the things I least wanted to be confronted with as a defence specialist and find ways of introducing them into our attacking game,” Ford told Chris Hewett last year.

Indeed, Ford’s Bath side have been making defences entirely uncomfortable since he was appointed in 2012, never more obviously than during the season just ended.

The Somerset club showed that they still have strides of progress to make in play-off rugby with last weekend’s Premiership final defeat to Saracens and a Champions Cup quarter-final loss to Leinster, as their set-piece, restarts, kicking strategy, backfield positioning and error count let them down at different times.

That said, Bath have played some of the most attractive rugby in the world as Ford has brought to the fore his experience both as a defence coach and a former rugby league international.

The likes of his son George, Jonathan Joseph, Leroy Houston, Anthony Watson and veteran Irishman Peter Stringer have all thrived in Bath’s approach to attack. While there are many strands to that attacking game, we focus on some of Bath’s structure in phase play in this piece.

Polished diamonds

Bath’s 47-10 demolition of Leicester in the Premiership semi-finals was perhaps their signature performance of the season, particularly as we saw the very best of their structured phase-play attack.

Inside the opening two minutes at The Rec, Ford’s men underlined exactly how difficult they are to defend against when they get their shape right.

This score comes on phase three of an attack that originates with a lineout on the left, so it’s clearly something Bath have mapped out. The real key to what unfolds on third phase is a simple bit of structure that allows Bath’s excellent attacking players to use their undoubted skills.

Talk of structured attack can lead us to think of slow, negative rugby, but Bath’s simple shapes facilitate and encourage their players’ creativity and skill.

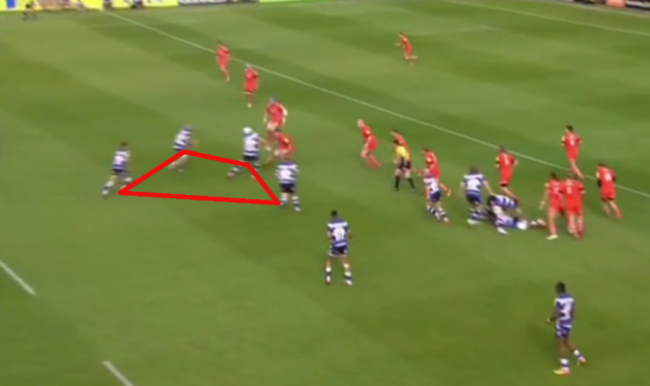

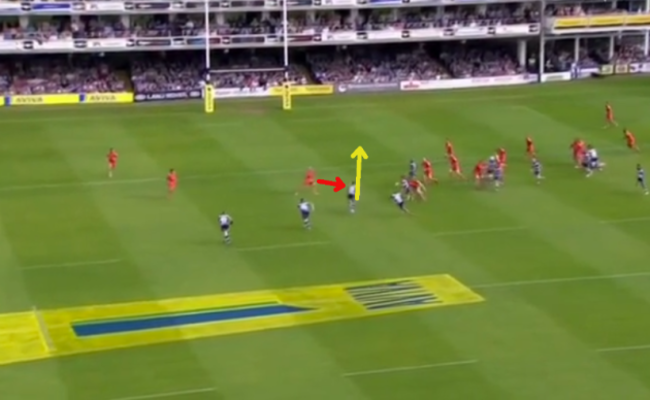

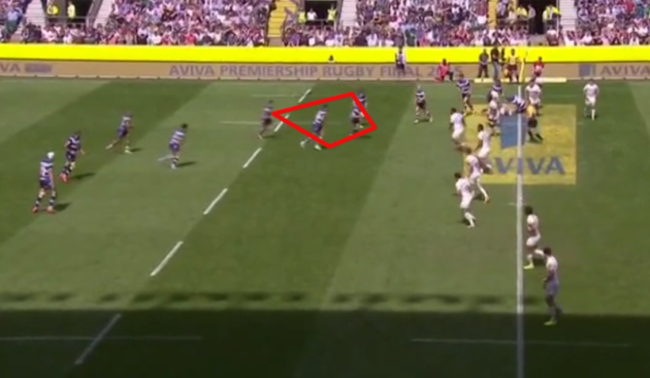

The first movement in this particular attack comes with the use of the ‘diamond’ shape that Bath have used time and time and time again this season.

It’s obviously not the perfect diamond in reality, but the shape is quite clear from Bath.

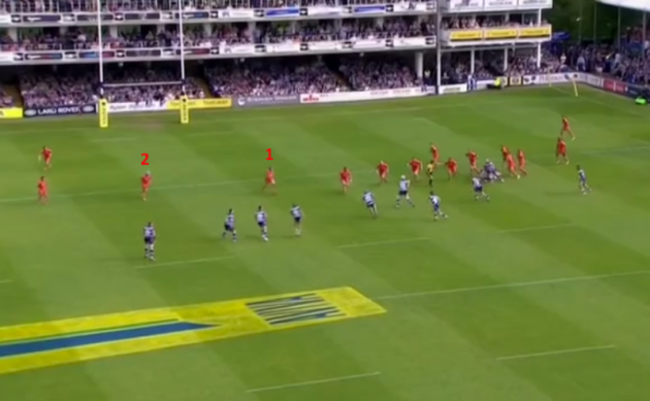

Dave Attwood is marked ’1′ in the shot below and he’s the passing player in the middle of a trio of forwards. On his left is Leroy Houston, marked ’2′, who is available for a short pass to Attwood’s left.

’3′ is prop Paul James, who first acts as a shorter passing option for scrum-half Stringer before becoming an inside pass possibility from Attwood. Finally, out-half Ford is marked ’4′ and he’s the player providing depth at the back of the diamond.

Ford is the second ‘wave’ of attack for Bath, supplying an option for Attwood ‘out the back door’.

That allows Bath to draw defenders in towards Attwood and his threat of carrying the ball or dropping off a short pass to Houston, but then release the ball deeper to give the out-half time to make a decision.

It’s important to note that every single player here needs to be a realistic option. Attwood must watch for a carrying chance himself or space to slip Houston into a hole, while James must attract defenders both before and after Stringer releases his initial pass.

This time, Bath go to Ford at the back of the diamond and Bath then strike with another basic piece of structure.

As the ball arrives in Ford’s hands above, the Leicester defence is already stretched. It’s the entire point of these structures, giving a player like Ford the chance to use his decision-making skills against an uncomfortable defence.

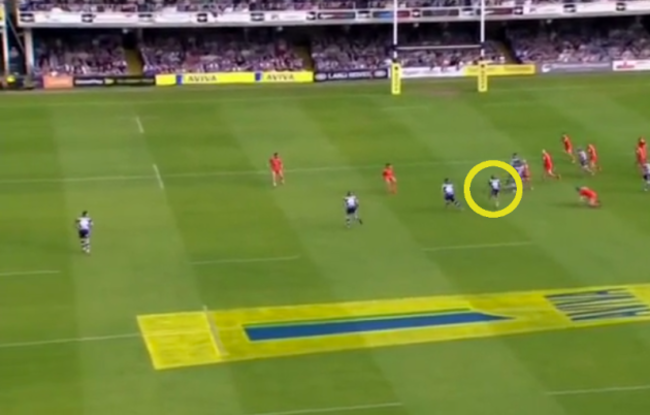

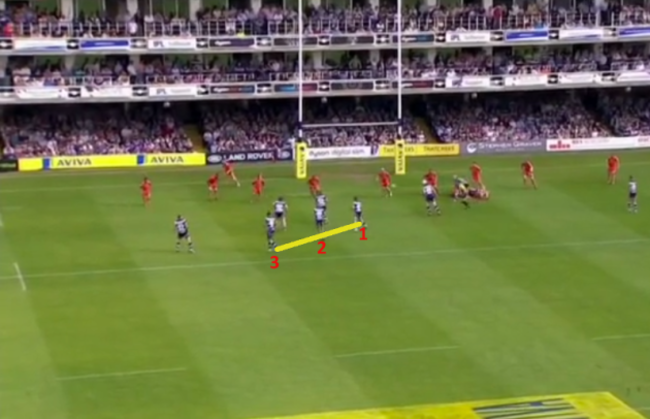

That there is a second element to the shape allows him to be even more effective in exploiting the defence. Ford is marked ’1′ in the image above, while outside him is Sam Burgess marked ’2′. Out the back door time this time is centre Joseph, signified by ’3′.

Burgess runs a short, hard line for Ford, while Joseph ‘bounces out’ from his deeper-lying position to provide a passing option out the back of Burgess.

Again, it’s important that both options are viable for Ford as they are in this case. The out-half assesses the situation in front of him and hits Joseph travelling on an ‘overs’ line and into space.

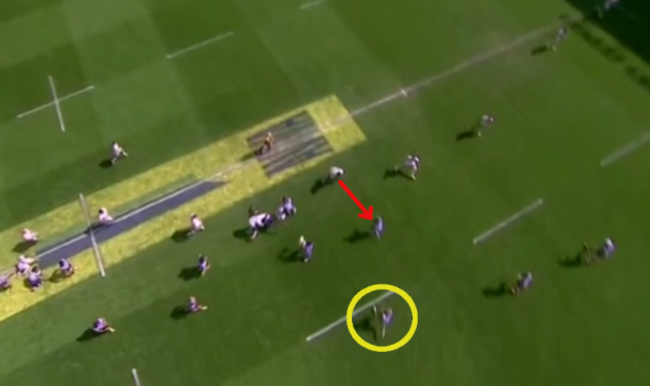

By the time the ball is in Joseph’s hands [he's highlighted with the yellow circle above], Bath have a four-on-two and an almost certain try. The England centre then gets the opportunity to show off his sublime attacking skills and provide an assist.

Let’s just jump backwards a little and take a look at what Bath’s structure does to the Leicester defence, and in particular Graham Kitchener and Jordan Crane.

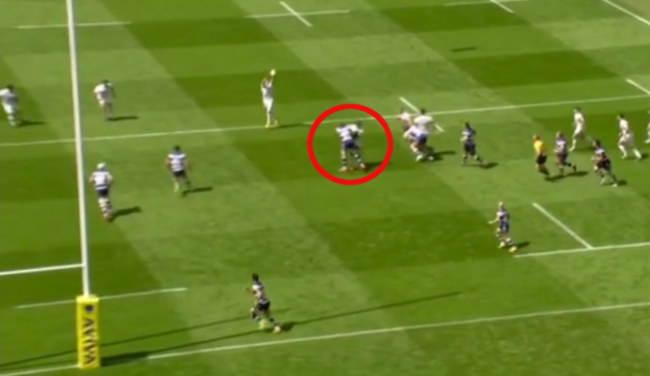

Second row Kitchener is marked ’1′ above, while Crane is labelled ’2′. Take a look at their actions from a different angle as Bath run their lovely structured play.

Just in case it’s difficult to pick out in the clip above, Kitchener ’1′ gets drawn in ever so slightly by Houston’s decoy line to the left of Attwood.

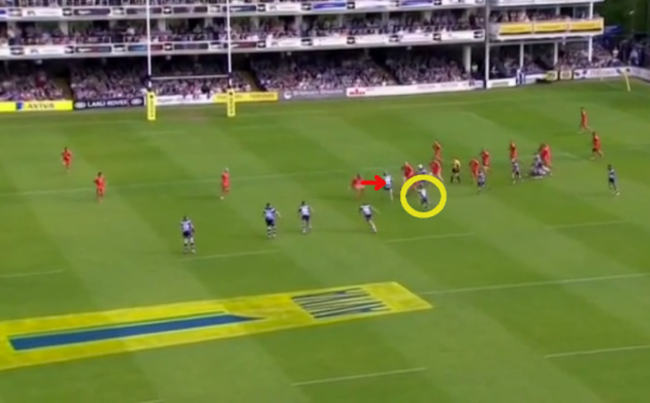

When we freeze the image below, Kitchener has just had his attention drawn by Houston [signified by the red arrow] as the ball is passed out the back to Ford. The ball is, however, arriving into Ford’s hands out the back [yellow circle].

That leaves Kitchener having to get himself moving again in order to tackle Ford. The out-half’s darting pace allows him to beat the lock with relative ease and Leicester’s defence is in an awful position.

Cue a big defensive decision for Crane, one he would “least wanted to be confronted with”.

Burgess runs the hard line that proves to be a decoy line [yellow arrow] simply because Crane is drawn onto it [red].

Had Crane opted instead to drift out and cover the back-door threat of Joseph, Ford would have simply broke himself or slipped the short pass to Burgess to run through and score.

Multi-optioned, multi-layered; it’s a stunning attack from Bath that uses structure to get the very best from their talented and highly-skilled players.

Double blocker

Watching Bath use these types of play is like watching a quality rugby league team and there’s little doubt that Ford’s attack is inspired by the 13-man code. His son George grew up in league too, meaning he is well versed in the clinical attack of that code.

Bath’s second try against Leicester in the semi-final was similar to the first, but it also highlighted the importance of having forwards who are capable of organising themselves and making good decisions.

This score came on the seventh phase of an attack that originated when Bath gathered in one of their own restarts. That means there is far more onus on every player in the jigsaw organising themselves. There’s no time to take a breath and call an exactly-planned power play; instead the structure has to shift into place on the move.

As we’ve already mentioned, it’s an extremely similar play here, as a forward makes a linking pass out the back door to Ford, who in turn hits Joseph behind a decoy runner, whereafter the England centre assists the score.

What we’re going to focus on here is the Bath forwards’ ability to be the organisers, their intelligence in creating the try.

Hooker Ross Batty, marked ’1′, and prop Nick Auterac, ’2′, are highlighted above as they signify their roles in the play.

Scrum-half Stringer has his head buried in the ruck attempting to free the ball, but the signalling actions from Batty and Auterac are important nonetheless. Batty is putting his hand up as the central man in the Bath diamond, while Auterac is signalling a connection with the hooker as the running option outside him.

When we move play on a few split seconds, we can see second row and captain Stuart Hooper signalling that he will be the ‘decoy’ runner on the second portion of the attack.

Having forwards take responsibility in this manner is pivotal to attacking well as a team, joining up the backs and forwards into an effective 15-man game. It’s worth noting that out-half Ford actually begins this phase behind the ruck.

Ford is not there to ‘boss’ his fatties around and put them into position, but he doesn’t need to be, nor should any out-half. This score demonstrates the importance of intelligent forwards who understand their team’s structures every bit as well as the halfbacks.

Just as important as Batty, Auterac and Hooper are Attwood and Houston. Second row Attwood is the man closest into the ruck, not quite joining up to form the diamond but certainly interesting Leicester’s fringe defenders.

Meanwhile, Houston is holding width on the left touchline, therefore eventually creating the hole for try-scorer Matt Banahan to run into. Selfless, intelligent play.

While those Bath forwards are organising themselves as front-line players, the crucial trio of backs in behind are moving fluidly to provide as many options as possible.

Joseph, marked ’2′ above, is initially in the back-door position behind Batty, but he realises that Ford , ’1′, has arrived and can take that role. The centre simply slides out one position to run the overs line behind Hooper instead, while Banahan similarly shifts out one slot.

All three of Ford, Joseph and Banahan do superbly to ‘bounce out’ on their outside line, essentially doing their best to remain hidden before darting into the space created by the decoy runners.

Bringing it all together, the below clip shows the beautiful Bath structure from behind and it’s worth focusing particularly on the actions of Auterac and Hooper this time.

Both Hooper and Auterac get good blocks in ahead of the ball on what prove to be decoy lines. The key is that they are ‘alive’ as running options until the very last moment, drawing defenders towards them and ensuring the referee doesn’t see their actions as blatant blocking.

Clinical, effective attack with the forwards all proving to be the key men.

Anyone who watches even a handful of rugby league games per season will recognise the above plays as distinctive of the 13-man code. Even scanning through a recent league game, that between the Broncos and the Cowboys in the NRL, we find an example that is almost identical to the Bath try above.

Those two passes from the Broncos behind decoy runners tie down defenders, before a skillful back in the shape of Darius Boyd straightens the line superbly and slips a teammate through the hole.

With Ford coaching and the likes of his son George and former league international Kyle Eastmond in their ranks, Bath are naturally influenced by the 13-man game. Even the passing style of Eastmond and his fellow backs often follows the end-over-end league approach, so it’s little surprise that some of their best structured play is league-esque.

Facilitator

We’ve already alluded to the fact that the best structures in rugby are created with the intention of allowing a team’s players to show off their skills. One of Bath’s tries in last weekend’s Premiership final underlined that, as Joseph again created the magic.

Such is the excellence of many defences in modern rugby, one-on-one situations are increasingly rare, never mind overlaps. But players like Joseph thirst for them, require them and absolutely thrive on them.

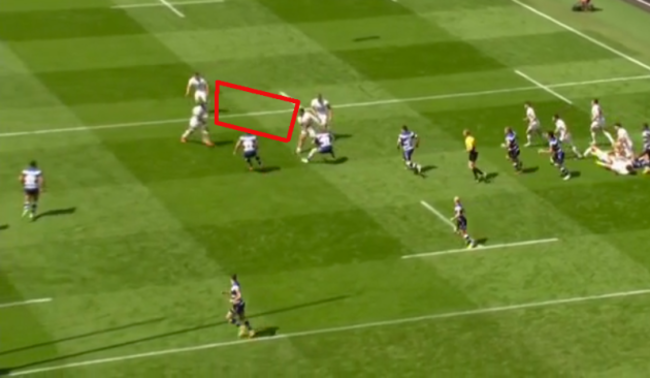

Bath do an excellent job of setting one up for their outside centre with another simple pullback pass behind a decoy runner here. Aside from Joseph, the key player is again a forward, Houston in this instance.

The back row runs a brilliant decoy line for Bath, leaving himself open for a short pass from Ford until the ball has gone out the back, and also ever so slightly arcing his trajectory back out towards the right touchline at the last split second.

It results in the collision highlighted above, taking Jackson Wray out of play for long enough to provide Joseph with a direct one-on-one against opposite number Duncan Taylor.

Joseph’s sublime footwork and acceleration do the rest of the damage.

Ultimately, Saracens’ failure to fold from their right side of the ruck left them numbers down here, but the simple screen play from Bath is exquisitely executed to show that even with fewer bodies in place, Ford’s men can still organise themselves to discomfort the defence more than simple one-off carries would.

No easy task

It’s possibly not necessary to point out, but Bath’s structured play doesn’t always result in them scoring tries or breaking the gainline. There are many examples where they’ve selected the wrong option or been inaccurate in their execution, as with any other team in any other aspect of the game.

Ford’s men actually conceded a try on account of the failure of one of their second-wave plays in last weekend’s final against Saracens.

It’s a simple dropped pass here, but there is some excellent reading of the attacking intention by Saracens to partly force the error. The defensive players bite down on the decoy runners far less than in the earlier examples here, forcing Bath to make a better decision.

Eastmond opts to hit Batty short to his left after taking the back-door pass from Ford here, but the hooker appears not to be expecting it. This simply highlights the absolute necessity for every option to consistently be a viable one.

Simply going through the motions of running a line isn’t enough. Batty has to expect the ball, even if the general likelihood of Eastmond going out the back door is far greater.

This example also shows that carrying out these structured phase-play attacks is demanding on the players, both mentally and in terms of skills. In the face of an aggressive defence, there is a huge onus to execute perfectly and remain utterly focused.

Rewards

That said, the rewards of joined-up thinking, organisation and execution can have hugely positive results, as Bath have been demonstrating on a consistent basis this season.

Saracens did wonderfully well to limit Bath’s chances to bring their decoy plays to the fore last weekend at Twickenham by being aggressive in defence and playing an intelligent territorial game, but there were still glimpses.

The example above shows that the back-door player can be a huge threat himself when he doesn’t simply serve as a passer out the back of a second decoy runner.

The play starts with Bath in their diamond shape, as Ford provides the back-door option behind the initial trio of forwards.

Prop David Wilson is the man at the front of the diamond, the passer, and crucially delays his pass to Ford for long enough to attract Saracens’ Maro Itoje into levelling him just after he releases the ball out the back.

To Wilson’s right is the decoy-running Burgess and he also succeeds in tying down a Saracens player, Mako Vunipola, as we’ve highlighted below.

Burgess’ success means every Saracens defender inside Mako Vunipola is realistically out of the game, and it leaves his brother Billy in a real spot of bother.

Billy expects Mako to be able to drift out onto Ford as the pass arrives in Ford’s hands, and his attention is therefore directed towards Rob Webber, the next man out in Bath’s attacking line.

We’ve indicated that below with a red arrow, but it’s also worth pointing out that Bath have Joseph lying deep outside Ford [yellow circle], ready to bounce out from behind Webber in a manner similar to the other examples from earlier.

It all places more decision-making stress on Vunipola, meaning he never really addresses the threat of Ford breaking himself.

As we’ve mentioned before, these structures are all about providing the attacking players with opportunities to use their skills and here Ford has the vision and pace to identify the gap rather than simple go through the motions and hitting Joseph behind Webber on a second decoy play.

Ford takes the space and breaks through Sarries’ line. No try follows, but this incident once again shows Bath at their phase-play best.

Not the only ones

Ford’s Bath are far from being the only team to use these kinds of shape in phase play. Look at any rugby game in the Pro12, Premiership, Top 14, Ulster Bank League or anywhere else and you’re likely to see these exact structures or variations on them.

Bath are often a cut above the rest in their execution and because they have players like Ford and Joseph who are so good at taking advantage of the opportunities presented, but other teams have great success in this department too.

A readily-available example comes in the shape of Saracens, who were absolutely superb in last weekend’s Premiership final as they earned a completely deserved 28-16 win.

Above, we see Saracens use the diamond shape to give out-half Owen Farrell time to launch a cross-field kick to David Strettle.

Billy Vunipola is the passer, as he so often is for Sarries, while Itoje’s decoy line to the number eight’s right is pivotal.

We can see below how Itoje draws Bath captain Hooper onto him, taking the defensive linespeed out of the equation and allowing Farrell plenty of space in which to get his kick away.

Outside Farrell, there is another pod of forwards running hard lines to provide even more deception, even if it’s not as slick as some of the best play we saw from Bath.

There were lots of other similar examples from Saracens in this final, although they never managed to bring a second pod into play after the initial diamond shape. Much of the time, they ran more traditional alignment as the second wave.

The influence of rugby league is clear though, and anyone watching the first State of Origin clash between Queensland and New South Wales last week would have been able to relate lots of the Premiership final back to that game.

The above screen play from NSW is about as basic a rugby league shape as you can get, and indeed as we’ve already seen that its crossover into union is complete. This hasn’t happened overnight by any means, but union teams are getting increasingly effective.

Those pullback passes behind a decoy runner are not the only thing union has borrowed from league. Indeed, we’ve spoken on numerous occasions in the past about the influence of league defence on linespeed and choke tackling in union.

The similarity between the second wave of Queensland’s attack above and the Sarries play below is certainly just a coincidence in which both of them occurred in the same week, but it shows the crossover of the codes.

Sides like Bath and Saracens have learned much from rugby league and have developed structures in their attack that allow their players to bring their decision-making and skills to the fore.

What have you made of Bath’s entertaining season? Does their structure in attack make them a more potent force? Do any Leinster fans out there recognise these shapes? How difficult are they to defend against?

Scousers don’t care about this game. More interested in Utd losing to Spurs.

@Olllie B: No not really you don’t have to be from Liverpool to be scouser. Northern Europe sailors brought a stew recipe to ports in England but mostly Liverpool. The dish was called Lobscouse. Those people in Liverpool who ate it were called Scousers.

Huddersfield fans out in force I see… who knew?

Come on Huddersfield

Well its Huddersfield for me…

If Klopp loses this…he’ll have to walk alone !!

@dannyboy: never!!

@Joe Kennedy: tbf Klopp is a joke at this stage.

But but but No Coutinho??? Ahhhh sure the January transfer window is nearly upon us so his back is probably playing up again

@powerfix: numbskull

If that defence is correct, I give up.

Im not even sure Lovren shagging Klopps missus would put him out of the team, Might be his downfall.

So Lovern’s punishment for being absolutely useless last week and costing his team 2 goals is to be rewarded with another start? The mind boggles

@Brian O’Loughlin: its common knowledge amongst real pool fans that lovern’s Mrs ran off another guy. So idiots here should really give him a break.

$hit happens to everyone from every walk of life. If things happen in your personal life that effect your performance or prevent you from doing your job properly you shouldn’t be there. Would you want a depressed pilot flying your plane? How is putting him in the firing line supposed to help him anyway? If anything it will make him worse

@Mr Nimziki: oh lord. You drop him till his heads right ffs.

@Nial D: so kick a man when he’s down is the answer

Klopp took off Lovren after 30 mins last week but now he’s starting again wttttfff

Sacked by your best man…,you’re getting sacked by your best man … sacked by your besssst mannnnnnnn ..you’re getting sacked by your besssst mannnnnnnnn….

@powerfix: nitwit

@powerfix: Jeez. My 12yr old has more imagination, and he’s far less childish than that. I’d say your parents are very proud.

If we don’t win kiss top 4 goodbye YNWA

@Ollie Watson: that ship sailed ages ago dude. Ye will be lucky to nick Thursday night ball next season.

Well wagner said he best friends with klippty that goal proved it

Is Coutinho dropped?

@Nollaig Elliot: “injured”

Time to get a run going after some recent blips

Glad for Sturidge to score his first goal in two months great player