IN THE NOT too distant past, boxing was king in New York City.

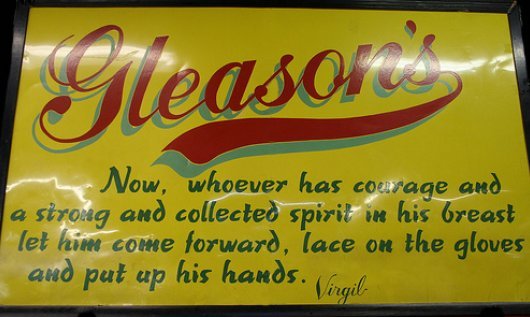

Madison Square Garden in the city is known as the Mecca of boxing, but Gleason’s Gym is the temple where many of the world’s greatest fighters perfected their craft long before they danced under the lights.

The most famous gym in the world, in November Gleason’s moved from its address under the shadow of the Brooklyn Bridge. It only relocated a block away, closer to the waterfront in Brooklyn’s Dumbo district, but waved goodbye to over 30 years of sweat, grime and blood from its tenure at 77 Front Street.

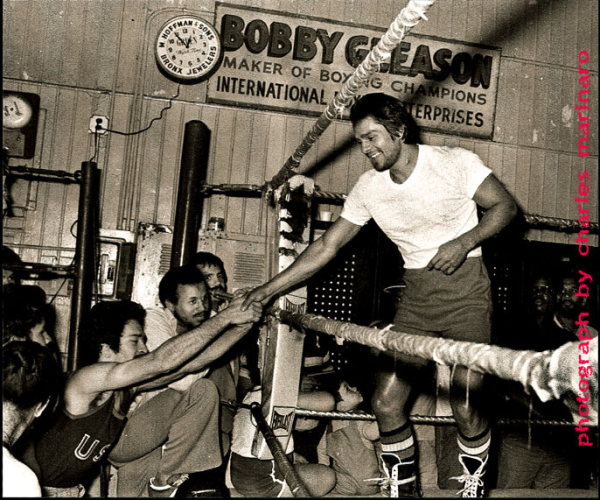

Entering the gym’s home from 1986 to 2016 was like taking a time machine into the past. The Havana of boxing. Walking up the steps to the arena on the second-floor, you could hear the speed bags going thwap-thwap-thwap, and the short crack-crack of the jump ropes whipping off the hardwood floors before you entered.

Inside, it was an intimidating scene. There was no music or air conditioning. The smell of sweat hung in the air as brutes battered against the heavy punching bags. Right-left-right-left-right-left. Men wearing headgear traded blows inside the rings, while others worked on their shadow boxing in front of cracked mirrors.

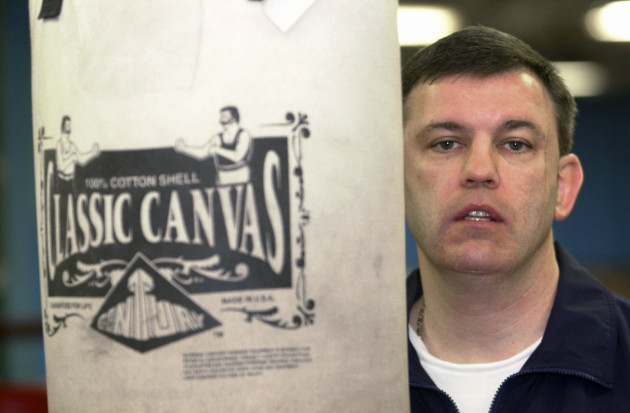

“It was a really rough, old school gym,” unbeaten Irish professional welterweight Jimmy McMahon, who trained there in the 1980s and 1990s, tells The42.

“With heavy leather punch bags, the smell of sweat and no real great facilities as far as a gym goes. But it was a tough gym. You had to be able to fight. You came and you were going to get put in the ring. You were either going to swim or drown. That’s the way that gym was.

“You wouldn’t leave your wraps on the seat where you’d get changed or someone would come and steal them. Even your shorts they’d take. When Gleason’s Gym first moved there you wouldn’t walk down Front Street. It was a rough area.

“That was just the way it was. It was a tough environment. But it was a great gym. If you wanted to be a fighter it was the place to go.”

Gleason’s is the last real surviving link to boxing’s glory days. Founded in the Bronx in 1937, it relocated to Manhattan in 1974 before migrating to Brooklyn in the mid 1980s.

In all its reincarnations, some of the greatest fighters to ever lace up a pair of gloves learned their trade inside its four walls.

“Raging Bull” Jake LaMotta was one of the earliest world champions to train in Gleason’s, followed by iconic figures Gerry Cooney and Roberto Duran. Numerous other legendary fighters made the gym their home away from home, including Wilfred Benitez, Julio Cesar Chavez, Larry Holmes, Michael Spinks and Tommy Hearns.

“Some the best champions of the heyday of boxing here in New York trained and were developed out of Gleason’s,” says gym owner Bruce Silverglade. ”It was an exciting time.

“A lot of good stories. When we first moved from Manhattan over to Brooklyn and had five rings, we would have world champions train in every ring.

“We had Arturo Gatti, Kevin Kelly, “Boom Boom” Johnson, Junior Jones all training there at the same time. Then you would have people like Iran Barkley and Juan LaPorte there.”

The gym quickly became a magnet for boxing’s biggest stars. Whenever a big-time fighter arrived in New York, at some point or other they ended up training at Gleason’s.

In total 134 world champions have practised inside the gym’s hallowed walls, none more famous than Muhammad Ali and Mike Tyson.

“Ali was a clown,” Silverglade continues. “Always loved people, always wanted to be entertaining to people. He was always pulling tricks. If any woman was around he’d make sure he hugged and kissed them. He loved the women. Any of the kids or men that were around he would certainly talk to them, take pictures and sign autographs.

“He was a people person, he loved people. When he was on TV talking and clowning around and saying his poetry, he was doing that because he was trying to sell tickets. One-on-one or in the gym environment, he was a total gentleman. Again, he just loved people and loved to have a good time.

“When he was training he was here every day and after that he would come in if there was something going on in New York. After he stopped training, he would continue to come into the place and make himself well known.

“He would stop by and say hi. He always liked the gym, he’d always come up here and pay attention to us.”

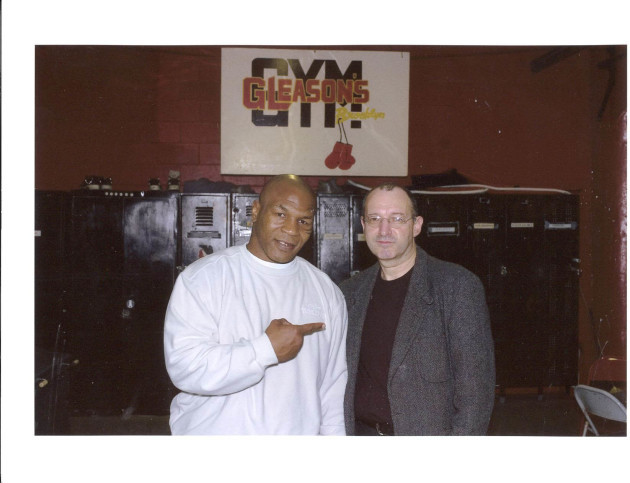

Tyson, who at 20 became youngest boxer to ever win the WBA, WBC and IBF heavyweight titles, grew up near the gym’s current location in Brooklyn. Despite his reputation as “The Baddest Man on the Planet,” Silverglade says he was nothing but respectful when he trained there.

“This is his home and this is the place where he liked to be. He was very accommodating to everyone. He appreciated the men and the women that wanted to come in to try and learn what he could do, what his profession was.

“He was always very polite and nice in the gym. The things that happened when he was out of the gym at night time, when he was either drinking or doing something else, I only know what you know. I only know the stories that I’ve read in the paper. In person, he’s always been a gentleman, particularly in the gym. He’s just a real, real nice fella.

“He used to have an office here too. He no longer does. He got out of promotion business just about a year ago. When he got out of the promotions he gave up the office.”

There’s also a significant Irish connection to the facility. As well as McMahon and Cooney, several Irish prizefighters including Barry McGuigan and John Duddy worked out at Gleason’s.

But the gym’s association with the Emerald Isle goes back far deeper than that. Its long identification with the Celtic culture can be traced back to its founding in 1937.

“The original owner’s name was Peter Robert Gagliardi,” explains Silverglade. “He was an Italian. He started the gym in 1937 in an Irish section of the Bronx, New York. It was also just before World War II, so a lot of people were upset with the Italians because of the war.”

So Gagliardi christened the gym Gleason’s in order to hide his Italian roots and appeal to the local Irish community, in the Bronx, with whom boxing was hugely popular.

“He had a fighter by the name of Gleason so he used his name and it became a hit right away. Then he legally changed his name to Bobby Gleason, and it was known as Bobby Gleason’s Gym. When I bought it I trademarked the name to Gleason’s Gym.”

Jimmy McMahon was just gone 17 when he walked through the doors of the gym for the first time, not long after emigrating from Mullhussey, Co. Meath in 1986.

“There was nothing in Ireland,” McMahon says. “There was a major recession going on there at that time. I think it was the most people that left since the famine that year. My brother was over in New York and I moved over to him. At that time it was a different era, you just got on with it.”

The son of two farmers, McMahon had been a junior Leinster champion in Ireland before he left, training out of Enfield and Kilcock boxing clubs. He moved to the Big Apple in August of ’86 and in October his brother brought him along to Gleason’s for the first time.

“It was a very professional gym. There was a lot of world champs there so it was pretty big. I started training and there was an Italian guy there, Joe Baffi, who trained a lot of fighters. Joe took me under his wing.

“Tim Witherspoon was there, the heavyweight champ of the world. Julio Ceaser Chavez was training there at the time. Juan LaPorte was there too. There were so many. Aaron Davis was up and coming, who I used to spar with a lot. He became the welterweight champ of the world.

“I wanted to be a fighter and I wanted to train there. I didn’t want to train at all these other gyms you could have trained as an amateur. I wanted to go there.

“I ended up sparring with some of the best fighters in the world. I sparred with world champions, I sparred with Davis and Julio Ceaser Green, the middleweight champ of the world.

“Gleason’s is probably the most famous gym in the world. When I was there in ’86, I think it had about 90 world champions come out of the gym already.”

McMahon fought 61 amateur fights in his first four years in New York, finishing with an impressive record of 55-6. He made the finals of the New York Golden Gloves three times, considered among boxing aficionados as one of the elite amateur boxing competitions in the United States.

“I was fighting mainly around New York,” he says. “I fought against Ireland one year when they came over in the year of the Olympics. I beat Paddy Keogh, who was an Irish champion at the time.

“The last year I fought in the Golden Gloves was ’91. I was against same guy again, Sean Doherty, who beat me twice before in the semi-finals. They were controversial losses. I felt like I beat him pretty convincingly the third time and I didn’t get the fight. So I decided, I wasn’t going to fight amateur no more.”

Fed up with the amateur game, McMahon turned his focus towards the professional ranks. There were plenty of suitors, but McMahon was snapped up by the renowned trainer and manager Teddy Atlas.

Atlas was no soft touch. He famously helped train a teenage Tyson before an altercation in 1982 saw them part ways. Tyson, 15 at the time, was sexually inappropriate with 11-year-old female relative of Atlas’s at his home. Atlas responded by putting a .38 caliber handgun to Tyson’s head and said he’d kill him if he did it again.

“I turned pro in the Madison Square Garden in ’92,” says McMahon. “I had two fights in New York and then I started fighting in Atlantic City at the Taj Majal, Donald Trump’s place at the time.

“I think I was 8-0 the first year. Then I went to do this medical and they found a little murmur in my heartbeat. They said they didn’t like it, but thought I might just be a hyped-up guy. So they let it go and I passed the test that year.”

In 1993, his second year as a pro, the opportunity of a lifetime came up. Atlas wanted to try and move McMahon around Europe to raise his profile.

He managed to get his young fighter onto the undercard of Wayne McCullough’s bout against Boualem Belkif in the National Basketball Arena in Tallaght, Dublin. Prince Naseem Hamed was another big name on that card.

Defeating Dave Lovell that night on his home soil was a proud moment for McMahon. Along with making his pro debut at Madison Square Garden, he ranks his only pro fight in Ireland as one of his career highlights.

“All my family, friends and everyone came up to Tallaght that night. It was a big night. It was great to do it. It’s a fond memory. My father got to see me fight professional.

“I got dropped once in my career and the place I got dropped was in Tallaght that night. I got dropped by Lovell but I got up and won. I was winning all the rounds, it’s just in that round he caught me.

“That was the first time I’d ever been dropped. Until you get dropped you don’t know will you get back up. That’s the thing about boxing, you don’t know.”

His career continue to go from strength-to-strength. A couple of fights later he travelled to Atlantic City for a bout against Bobby Heath, who was quickly making a name for himself in America.

“I’d say my toughest fight was probably Bobby Heath. He was a good puncher. He was 5-1 and I was undefeated, so that was a tough fight. But I beat him.”

At the end of his second year in the pro ranks, McMahon’s life was turned on its head. He went for another routine medical, which was required to be granted his licence for a third year of fighting. But the doctors were worried that the murmur in his heart was still there, and they couldn’t figure out why.

“We don’t know what’s causing the murmur to go high and low,” they told him. “But we think it’s better if you don’t fight no more.”

“So they took my licence,” says McMahon. “I was 22 and I was forced to retire, basically.

“It was hard at the time because I was at it everyday and I loved the game. But I did realise, if there’s something there it’s there. There’s nothing I can do about it.

“At first it is hard but then you realise…I moved on. I moved on in life. I’d no choice.”

McMahon retired unbeaten after 15 fights, with 14 wins and one draw. Does he ever wonder what might have been?

“The guy I beat Bobby Heath went on to have a good career after. He won the NABF welterweight title. He fought a lot of top names and I beat him pretty convincingly, so I’d say you know what…” his voice trails off. “You never know, you never know. It’s a tough, tough game.

“I got out of the game completely after that. Teddy Atlas flew me down to Vegas, he offered me something like an assistant trainer with Michael Moorer if I wanted it. But I wasn’t ready to train, I was too young. I was 23 by then. I had no interest. If I couldn’t fight I didn’t want to do it.”

The young Irishman left his boxing days behind, but the six years of work he put in at Gleason’s served him well in later life. With his older brother Michael, the McMahon boys moved into the business world and they soon started to replicate the sort of success Jimmy had enjoyed inside the ring.

“When you train in this game, you have to put everything into it,” he says. “So no matter what else you’re going to do after it, you’re going to have that same mentality to go about life. You have the same direction and purpose.

“We got construction companies going and started putting up our own buildings. Then we started buying up land. All the stuff you do when you’re young. We moved on to bars and real estate. My brother and I are partners in a lot of stuff.

“We’re in the publican game here, we’re in it in Ireland in Maynooth as well. We’ve a bar McMahons in Maynooth.”

Fortunately, McMahon had no health issues after he hung up his gloves. He lives with his wife Lynn and three kids Aidan, 13, and twins Kelsi and James, 7, in Belle Harbour. His home is on the border of Queens and Brooklyn, facing onto the North Atlantic Ocean.

In 2014, the brothers picked up a new watering hole on Fifth Avenue in Brooklyn. The famous Barclays Center looms large nearby, while a familiar name also owns property in across the street.

“That’s Jay-Z’s club over there,” Jimmy told the Brooklyn Eagle during a tour of the property in 2014, as he pointed towards the rap mogul’s 40/40 Club.

“We’re the Irish answer to Jay-Z.”

Just like McMahon, Gleason’s Gym has moved onto pastures new since the ’90s. It wasn’t long before Hollywood studios fell in love with the gritty nature of the gym and it became a popular venue for shooting locations. Martin Scorsese directed Raging Bull there, while, Clint Eastwood had Million Dollar Baby filmed at the gym.

“We’ve done 26 full-length movies at Gleason’s,” says Silverglade. “So in addition to making world champions we do really well in Hollywood. Four of our movies won Academy Awards so it’s busy. And it’s fun, it’s just a fun place to be because you never know who’s going to be on the phone and want to do something up here.”

They also train up the actors before they appear in boxing movies. Robert DeNiro, Hillary Swank, Jennifer Lopez and Usher are among the celebrities who learned how to fight there.

“When people come into Gleason’s they’re half intimidated, so you don’t have to worry about somebody being a diva or wanting a certain colour jellybean in their trailer. They come up, they’re intimidated, they don’t know what to expect. They’re just normal people like anybody else. It’s fun to have them up here.”

The clientele has changed too. Of the 1,200 people who now regularly train there, only 300 are there to fight. Silverglade estimates about 900 are there just to workout.

“Usher still trains here,” he says. “He did the Roberto Duran movie (Hands of Stone) but he continues to come back and train here. We have a lot of the celebrities that come here.

“A lot of top models come here too. They come here because nobody bothers them, they don’t have to worry about how they look or what clothing they’re wearing. They can just sweat up here and get a good workout in and then go home.

“Nobody makes a fuss over anybody up here. The only one we ever made a fuss over was Ali. When he came in the whole place would go crazy. Other than that it’s sort of water off a duck’s back.”

The gym currently has no male world champions training there, but they do have five female world title holders. As if the gym needed any more history, Gleason’s is the home of Jack Dempsey’s 90-year-old speed bag.

It’s also the place where the term “white collar boxing” was invented.

“We started white collar boxing about 30 years ago,” he continues “That’s because I was starting to get so many business men and women in the gym that I needed something for them to do.

“I couldn’t just train them and have nothing so we tried getting the amateurs involved and they weren’t interested. We tried to get the pros involved but they weren’t interested. So were started the white collar program, which is now worldwide. It’s a tremendous program and it’s been very successful.”

The oldest working gym in the world, Gleason’s is a place where everyone is equal. The new gym might be cleaner, with fresh paint on the walls and little blood spattered on the floors, but the old code remains the same. There are no clicks. Rich and poor, all races and creeds train side by side.

Silverglade also welcomes in kids from troubled backgrounds who can’t afford the gym’s $95 monthly fee, and lets them train there free of charge.

“I have a foundation, this is the 25th year of the charity. It’s called Give A Kid A Dream. We take the kids that are referred to us through police officers, penal institutions, parole officers, churches.

“Anybody that’s working with a troubled kid and they think the discipline of boxing would be a benefit to them and help them, but they can’t afford it, we take them in and train them at no charge.

“We bring them on field trips, we bring them on camps in the summer-time. We have a tutoring program for them and we try to do whatever we can for them.”

Silverglade, who has elephant-like powers of recall, even remembers McMahon’s days in the gym 30 years ago.

“Yeah a young kid, him and his brother used to come here. I remember them. Make sure you say hello, he was a great kid. His brother was a good kid too.

“He was a tough guy. All the Irish guys are tough guys, that’s why people like them. That’s why they sell so many tickets.

“They don’t necessarily become world champions but they have all the desire and all the heart in the world.”

Having watch 134 world champions train work his gym, what does Silverglade believe it takes to become a world champion?

“Desire. The only person who can make a person a champion is the person himself. The trainers don’t really matter, the gym doesn’t matter, the hangers-on and the advisers don’t matter.

“It’s up to the individual and you can see if the person is determined and whether he wants to do it or not. It doesn’t matter how much people cheer him on, how much people tell you what to do.

“You have to do it yourself. You have to do all the homework and all the hard work inside and outside the gym. When a trainer tells you, ‘Hey I got up early this morning and woke up my fighter and helped him run’ – that fighter is not going to be a world champion. The world champion gets up on his own and does his own road work.

“And Jimmy was like that. Just a tough Irish kid.”

The42 is on Instagram! Tap the button below on your phone to follow us!